"I think of painting -- in fact all the arts -- as a sort of extension of human life. The very same things that we value most, the ideals of humanity, are the properties of the arts." --David Park, 1959

In the Spring of 1978 I saw a retrospective of works by David Park (1911-1960) at the Oakland Museum. At the time, I was in my third year of college, a recently declared art major. More than any exhibition I had seen before, or any I have seen since, the Park exhibition spoke to me. "This is what art should be," I decided, "and I have found an artist I want to emulate."

I must have said something along those lines in the letter I wrote shortly thereafter to Mrs. Lydia Park Moore, Park's widow, now re-married. She wasn't hard to find: many of the paintings at Oakland were listed as belonging to "Mr. and Mrs. Roy Moore, Santa Barbara, California," and they were listed in the phone book. I don't remember exactly what I wrote, but I certainly did my best to tell Mrs. Moore about what I loved in Park's paintings, and I also asked if there was something small -- maybe a drawing -- that I could purchase.

For the past 32 years the letter she wrote to me in reply has served as my bookmark for the David Park catalog I brought home from Oakland. Written in a clear hand in blue ballpoint on elegant stationary, here is what it says:

May 3, 1978

Dear John Seed,

In a day or two I shall send you a "studio drawing" by David Park. A gift, no purchase!

When I read your letter I was very moved. If an artist, or any human being for that matter, can give another individual encouragement, hope, a desire to believe in his own work, then the whole effort is worth while.

If you are ever in Santa Barbara please come and see us. We have a few paintings here which are not exhibited very often, and you might like to see.

Sincerely,

Lydia Park Moore

About a week later a manila envelope arrived at my college PO Box. Mrs. Moore hadn't packed it with any great care, and it came out of the envelope a bit rumpled. When I later mentioned this to Park's daughter Helen Bigelow, she recalled that her father wasn't too formal about packing art either. "David once mailed me a small oil painting wrapped up in brown paper with string," she recalled.

The top edge of the drawing had been torn out of a spiral drawing pad, the paper was slightly yellowed, and it had no signature. Still, there it was: an original work by David Park, and a rather powerful one.

Park, who is credited with founding the "Bay Area Figurative School," was a painter who felt a strong connection to the human figure. He was something of a rebel in insisting on painting the figure when most American modernists were practicing abstraction.

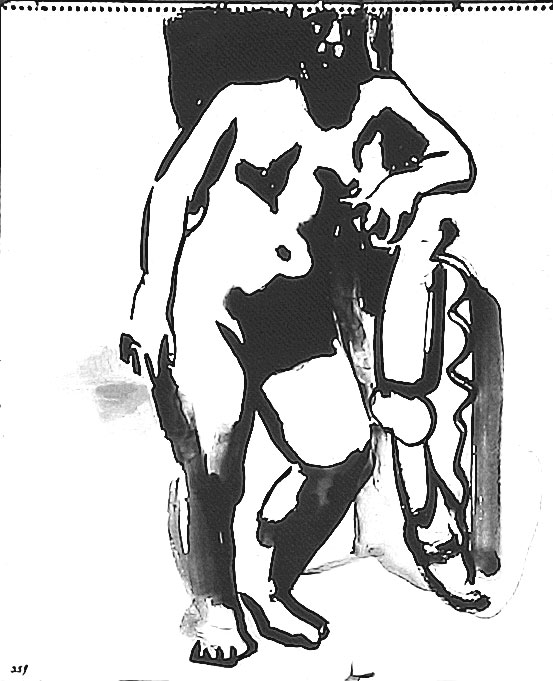

His late works portray the figure with powerful calligraphic brushstrokes that sometimes verge on caricature. The drawing that Mrs. Moore sent to me was a study of a female nude, executed mainly with a brush and India ink.

Her face was composed of a welter of dark strokes, with pools of ink for eye-sockets. Her body was rotund and maternal, the body of a contemporary Venus of Willendorf. Powerfully lit, she leans on something -- a stand with a robe? -- supported by blunt strong toes and tree-trunk legs. By no means a conventional beauty, she seemed to be some kind of archetypal woman charged with magic.

Of course, that was how I felt about her. If Park, who died of cancer in 1960, had been alive to chat with me, he might have said "That is simply a studio study of a large model I did in the late 50s."

I was working part time at a frame store, and I built the frame for the Park myself, using a heavy walnut molding that had some bulk to it. For the next ten years, it was always the first thing I hung up when I moved, and in my student years that was often.

In the summer of 1978 I followed up on Lydia Moore's invitation and a friend and I visited her home on Santa Tomas Lane in Montecito. She and her husband Roy Moore were very welcoming, and I enjoyed seeing the small handful of Park paintings she still owned including his last major oil "The Cellist." I remember Lydia Park Moore as being warm, just a bit scattered, and very proud of her first husband David's legacy.

I knew from having read and re-read my David Park catalog that Lydia Park had gone back to work in the early 50s, giving David what he gratefully called the "Lydia Park Fellowship" which allowed him to devote himself to painting. What he achieved as an artist had a lot to do with the devotion and support that she had provided.

For most of 1978 and until my graduation in 1979 most of my paintings looked like poor David Parks. I was heavy handed with my paint, and used broad cheap brushes from Standard Brands to apply my oil paint. In some ways my paintings were a success, as looking at Park loosened me up and took my paintings in a more emotional direction.

On the other hand, I didn't have the skills or experience in drawing to create the kinds of wonderful shorthand and sense of space that I admired in Park's late oils. I gradually realized that Park's works had a maturity about them, and as a young artist I would need to be very, very patient if I wanted to paint anything that came close to Park.

By graduation I owned four Park drawings. I had found that there was a large folio of them downstairs at Maxwell Galleries on Sutter Street, and the prices were low. I remember that one drawing of two figures on a beach was priced at $200 but I talked my way into a 20 dollar discount and got it for $180, paid in installments.

One of results of my interest in David Park was that I was determined to study painting with his remaining peers. In my undergraduate years I had studied with Nathan Oliveira and Frank Lobdell. Frank, in particular, remembered Park well and told me that he had helped carry buckets of paint scrapings from Park's studio during his final illness. Through a friend I was able to meet Richard Diebekorn, but when I visited his home in Santa Monica we mainly talked about Mark Rothko: Park didn't come up.

In 1981 I entered the MA program in painting at UC Berkeley, where Park had once taught. One day after class I saw Joan Brown, who had been one of his protégés, loading something into her car. She must have been in a hurry because when I walked over and tried to strike up a conversation, asking her "What was David Park like?" She gave me a one-word answer: "Sarcastic."

I learned more from Elmer Bischoff who told me quite a bit about Park's methods and ideas. He had been part of the group of artists who had drawn the figure together with Park at the California School of the Arts. When Bischoff came to my studio one evening for a group critique, he studied my Park drawing soberly. "Where," he asked me "did you get this?"

By time I finished grad school my paintings look much less like David Park paintings. I rarely painted the figure, and I had found my own idiosyncratic way of applying paint. Park would have approved. He once told his friend and biographer Paul Mills: "As you grow older, it dawns on you that you are yourself -- that your job is not to force yourself into a style, but to do what you want."

In 1989 I got a call from Paul Thiebaud, a young art dealer just beginning his partnership with veteran dealer Charles Campbell. He offered me a sum for my Park drawings that I found breathtaking, and I met him at the home of his father, artist Wayne Thiebaud to drop them off. In his father's studio he casually wrote me a five-figure check. After signing it, he asked me, as an afterthought: "What did you pay for these?" He was a bit shocked by my answer.

In the years since I sold my drawings prices for original works by David Park have risen as fast as CEO pay. A few years ago a single Park painting from his 1959 New York show sold for $2.7 million. What would Lydia Park, who had struggled to pay the $195 inheritance tax on her husband's estate after his death, have thought of that? I like to keep in mind that there was a time that works by Park were given as gifts, sent in rumpled manila envelopes or wrapped in brown paper, tied in string.

The money that I received for my Park drawings gave me the cash to turn a small one-room weekend cabin in the high desert into a real retreat with a bathroom and extra bedroom. When I sold it 9 years later I was used every penny from the sale of the cabin to pay the heavy costs involved in the adoption of my oldest daughter.

Still, I am embarrassed now by having sold the drawing that was once given to me as a gift. I wish I had it hanging in my office now as I write. I tried contacting Paul Thiebaud and asking about it not long ago, but he had no recollection of whom he had sold it to. A few months ago I read that Paul had died, of cancer, at age 49, just like David Park.

The drawing may be gone, but Lydia Park Moore's generosity has remained on my mind. I learned more about her when I read her daughter Helen Park Bigelow's excellent memoir "David Park, Painter: Nothing Held Back." It is an honest book that told me more about Park's struggles, his family, and what he was attempting to do in his art. I know for a fact that part of Park's achievement is owed to his wife who had most certainly given him "...encouragement, hope, a desire to believe in his own work."