The Radiant Child, a recently released film by Tamra Davis, and a Basquiat Exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler, have put Jean-Michel Basquiat in the news again. I viewed some of the interview footage used in The Radiant Child at the LA MOCA Basquiat retrospective in 2005, and I am very much looking forward to seeing the completed film.

Basquiat, who I knew for a few months in late 1982 and early 1983, made an indelible impression on me. It seems like a good time to share my recollections. The following essay, based on one I first wrote for my personal website in 1998, contains my most vivid memories.

A bit of background: when I met Jean I was 25, and had recently returned home to LA from Northern California, where I had earned a BA and an MA in Studio Art. Jean, who would have been 22, was a rising star on the New York art scene, spending time in Los Angeles preparing for his second exhibition at the Larry Gagosian Gallery.

* * *

When I met Jean-Michel Basquiat in the fall of 1982 he came to the door naked. I had been sent to Venice, California, where Jean was living in a former art gallery. Just a few days before I had been hired by art dealer Larry Gagosian, and had seen my first Basquiat Painting -- Skull, now in the Broad Collection -- at his gallery. Larry had explained to me that Jean needed some help around the studio.

Jean had probably just woken up -- it was early afternoon -- and led me his living space while wrapping himself in a towel.

The Venice Studio/Gallery where Jean lived and worked

He was living in a room that had only two pieces of furniture that I remember: a mattress with no box spring and a small TV set with rabbit ear antennae. As I later learned that he had once lived in a cardboard box in a New York park, the lack of furniture must have been a habit. I also found out later that he was paying Larry $2,500 a month in rent, and he certainly could have afforded furniture if he had wanted it.

The floor was covered with an amazing array of clutter: art history books, cassette tapes, art supplies, and clothing including lots of paint-spattered Armani suits that I later took to the dry cleaners in a plastic garbage bag. There were also drawings on the floor -- many with footprints on them -- and art supplies including oilsticks, paintbrushes and rollers. From time to time I also came across bags of marijuana, and wads of cash.

Jean-Michel never drove that I knew of -- an ancient Dodge that he had planned to use in LA had been stolen -- so I began to go over often, first to deliver the stretchers for him to paint on, and later to pick him up to run errands. Generally, he sat in my Toyota truck looking sullen behind dark glasses, speaking only to direct me to the next destination.

Jean was a big spender. When Madonna, just at the beginning of her celebrity, came from the East Coast to visit, I took him to the bank to get $5,000 cash. It was meant to be his pocket cash for the weekend. Another time, we walked into a local paint and hardware place and just cleaned out the art supply section. Jean-Michel, who cultivated a rasta street kid look, paid by tossing random piles of big bills on the counter so that the stunned cashier could do the counting. I also remember him buying a hundred dollars worth of Neutrogena soap at a Beverly Hills drug store.

One one errand I took him to the office of a doctor who was also an art collector. Jean was being treated for an STD and had arranged to pay for his treatment with drawings. On the way home he asked me to stop at a sandwich place he liked in Beverly Hills. He got out, and told me to just take a spin around the block and pick him up.

I got stuck in heavy traffic, and it took 20 minutes to get back. When I got there he didn't say a thing -- he was clutching a sandwich and glaring at me from the curb when I finally returned -- but three weeks later he walked up to me and gave me an utterly detailed description of how I should have taken certain back alley, and used a less busy street. He included street names and knew where I should have gone right, and where I should have gone left. Incidents like this began to show me how intense he was. Jean could remember details of all sorts and spew them out with real intensity at any moment. In many ways, that is what his art is about: intensely felt, but fragmented experience and knowledge.

Jean's heavy spending alarmed me. Once I told Jean that he needed to make investments, and that he ought to get a stockbroker so that if his career burned out he would have some money put away. He was furious, and immediately explained that there was absolutely no need for him to plan for the future. In his mind a star never had to worry about money, and I had insulted him by inadvertently suggesting that someday he his paintings wouldn't leap off the gallery walls.

After that I began to call him "Elvis," which was my way of kidding him about his out of control lifestyle. In response, he came up with "White Sambo Gringo," a jab back at me, his errand boy.

My life at that point was kind of like a twisted version of Driving Miss Daisy. I was a Stanford-educated, upper middle class white man, chauffeuring a younger African American art star who had never finished high school. With all respect to Tamra Davis, if I made a film about my experience of Basquiat it certainly wouldn't be called The Radiant Child, an oddly patronizing title borrowed from a 1981 essay on Basquiat by Rene Ricard. My film, Driving Mr. Basquiat, would be a very dark comedy about complex misunderstandings of race and class.

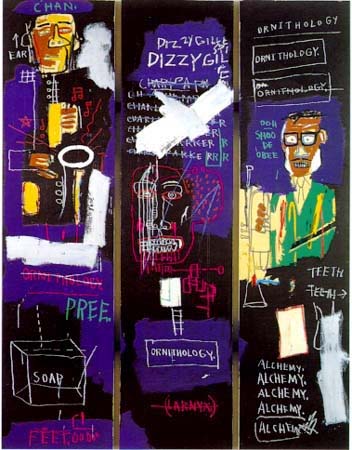

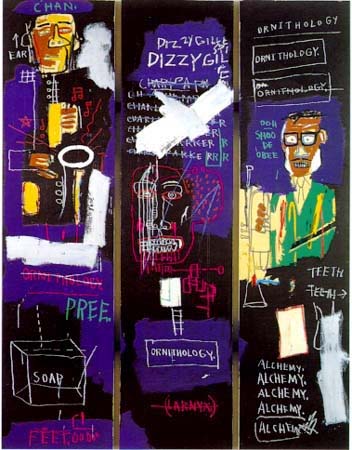

My other job, besides taking Jean out to buy art supplies and running him around town, was to build his stretcher bars and then prime them for his late night painting sessions that took place after he came home from the China Club. Among the canvasses I made were some triptychs, joined by Douglas fir 1" x 2"s and braced with plywood triangles made from shipping crates that had arrived at the Gagosian Gallery. One of these canvasses, which I had primed with black gesso, later became the "Horn Players" now in the Broad Collection. Working in my parents' garage I also made a series of large square canvasses, one of which became Hollywood Africans, now in the collection of the Whitney Museum.

Horn Players by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Collection of the Broad Art Foundation

Jean Michel, contrary to what you might think, absolutely did not consider himself a "Graffiti Artist." He had some friends like Ramelzee who did use that phrase to describe themselves, but Jean hated it. He once hung up on a woman graduate student who while interviewing him insisted that he was part of the Graffiti Art movement. He felt strongly that he was a fine artist, and his influences ranged from Leonardo da Vinci to Abstract Expressionists like Cy Twombly and Franz Kline. The influence of these and other artists is apparent in his best works.

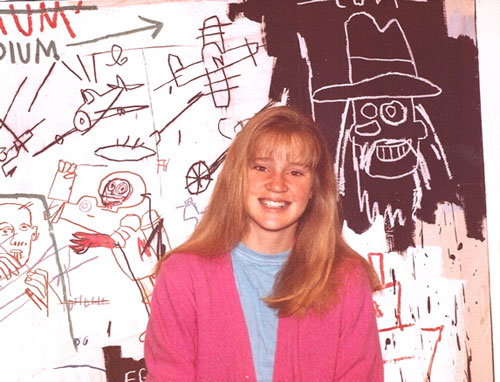

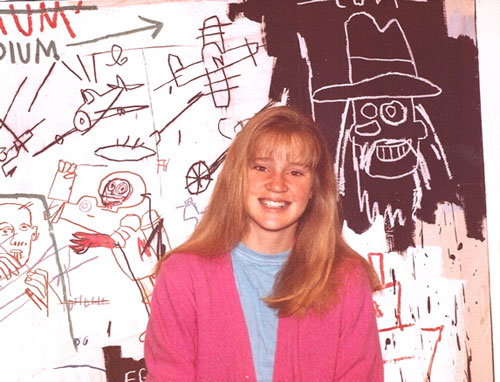

One day when Jean was away from the studio, I saw a striking five foot square painting leaning against the doorway and decided I had to have it. Titled Future Science Versus the Man, I later learned that it had been in Jean's show at the Fun Gallery in 1982, and that he had brought it to LA where he added to it.

Science was an electric painting, a revenge fantasy meant to mock "white" history and progress as depicted in high school textbooks. It featured line drawings of warplanes, steamboats, Buffalo Bill Cody, a bug-eyed cowboy in a ten gallon hat, and an astronaut figure whose helmet enclosed a manic "Day of the Dead" skull. It also included words and phrases -- carefully printed in Jean's earnest block lettering -- including "Radium," "Egypt," and "Fraud 1/2."

Underneath a three-pointed crown, a signature Basquiat image going back to his days as the tagger SAMO, the phrase "Ten Gallon" was carefully lined out and then Xed out. All of this was set on a black and white background that an would have made a striking Abstract Expressionist painting, complete with drips. Jean had a way of making images completely his own, and maybe part of what he had in mind was to graffiti over a Franz Kline.

I made a deal to buy the painting with Larry, who must not have told Jean about my purchase. That would cause problems later.

I had some money saved, and since I was living at home and not paying rent, I could put most of my salary into payments. I came up with the total of $5,000 in about three months and took the painting home. My parents were mystified, but there we were, a white middle class family living on the west side of Los Angeles with a Basquiat in the downstairs bedroom. Whenever my parents, now in their eighties, see a Basquiat in a magazine it gets their attention. After recently seeing the designer Valentino posed with his Basquiat in a glossy magazine spread, they were anxious to point it out to me.

The author's sister Janet with Basquiat's painting "Future Science Versus the Man" in 1983

After I took the painting home Jean phoned me several times and insisted that I return it. He said that it should go to a "major collector." I wasn't part of the art crowd, and as a social nobody I apparently didn't even deserve to own one of his canvasses. Having grown up feeling excluded because of his race, Jean took a sadistic delight in turning exclusivity around and making it his own tool.

To convince me to let go of the painting Jean offered me a deal. "I have done only two portraits, one of the artist Francesco Clemente, and another of Andy Warhol," he told me. "I will do your portrait, and it will be my third, and I will give it to you." I fell for it, gave the painting back to Larry Gagosian and got my money back plus a $500 profit. I felt like a slick art dealer for about 5 minutes.

It wasn't uncommon for Jean to show hostility towards people who expressed interest in his work. One example of this -- which was related to me by another Gagosian employee -- took place when the wealthy art collector and MOCA founder Marcia Weisman came to visit Jean's studio. When she arrived at his studio, he took an immediate dislike to her. While she looked uncertainly at his work he became defensive and silent, and worked on an oilstick drawing on a very large piece of butcher paper.

The drawing, which showed a sort of frightening caveman holding a bone, was a kind of cartoon parody of savagery. As Marcia was getting ready to leave he added a penis and testicles to the image and later told a gallery employee that it was a depiction of Mrs. Weisman.

Two Gagosian Gallery employees mug in front of the drawing Basquiat stated was a caricature of collector/patron Marcia Weisman.

Jean had his big show in the Spring of 1983, with the painting I had returned on the front of the invitation. The opening was jammed, and he showed up very late and very stoned, listening to a Sony Walkman. I think he really couldn't handle social pressure. A few weeks later, he went back to New York and moved into a loft on Great Jones Street that he leased from Andy Warhol. When I got the job of cleaning up after him I found my portrait among the junk he had left behind. It was painted on one of the cheap canvasses we had bought one day at Standard Brands, and it had a splashed red circle -- my face as a happy face -- in the center.

On the bottom Jean had written my name "John Seed" in oilstick, followed by "White Sambo Gringo" with a red arrow pointing downwards. The arrow, of course, was pointing me down to Hell. Somehow, maybe by calling him "Elvis" or daring to buy one of his paintings, I had brought out his deepest hostility. The portrait had a bit of voodoo about it, and it made me uneasy enough that I never hung it on my wall.

A few weeks later, when I cleaned out his studio, I sent my portrait back to Jean's New York studio in a crate, along with some other things of his. I have never heard of it since and hope it went into a dumpster as soon as it got there. Jean's painting was meant as an insult, and it certainly gave me a jolt. If anything, it got me thinking about racial tension and in a way that nothing in my life ever had before.

As I had discovered, Jean-Michel could be pretty awful. He also could be very kind and sweet, and The Radiant Child apparently showcases that side of Jean's character. In my presence he was often very paranoid about the people surrounding him, and he certainly was right to be that way as so many people were using him in one way or another. At least one of the people who was around his studio stole drawings, and I tend to think that Jean liked to be stolen from: he could then amaze the thief by confronting them and knowing exactly what they had taken.

Putting aside the bad experiences of him, I have to say that he made a positive impression on me as an artist. He really had what I would call "second nature," which means that his art was utterly direct and in touch with deep emotions. I do think of his art as being poetic, and also as being about the alchemy of signs and symbols. He definitely made powerful art about the problems of race, and the sheer vitality of his ideas and imagery continues to dazzle me.

I was very fortunate to know him at the peak of his creativity, but also unfortunate to see his growing paranoia and distrust of those around him. He was a very troubled guy. When friends have asked me about him, I tell them that I truly believe that if he had ever been sober for an extended period, he would have needed psychiatric help. It is a shame that he never got that help: I understand that several people later did try. When I knew him a lot of money was being made; apparently nobody wanted to mess with the "magic," and drug use was a part of that.

People have also asked me if I regret selling my Basquiat painting. Honestly, it would be nice to have something worth millions of dollars, but I shudder when I think of the trouble that painting might have gotten me into over the years. I did see it again at the Basquiat Whitney retrospective in 1993. My wife offered to take my picture with it, but a hovering guard wouldn't allow it. I didn't bother to try and explain that it had once hung in my bedroom.

Across the street from where I teach there is a Red Robin restaurant. Over one of the booths is the now iconic Halsband photo of Jean-Michel and Warhol posed as prizefighters: feisty outsiders who both slugged their way to art world fame. When I take my family there for dinner, I often glance at the poster, and think about the sadness of it. There he is, the guy who was once a young art star, and an artistic genius, now a dead poster god like James Dean, or Elvis.

Of course, maybe that is exactly what he wanted all along.

Authors Note, December 16, 2010:

I was recently able to view "The Radiant Child" and I thought it was very powerful. In particular, I thought that interviews with Basquiat's friends and contemporaries were very insightful. I do think that the film could have said more about the tough issues of how Jean was exploited and how he in turn created his own problems.

John Seed in front of a Warhol/Basquiat poster, Red Robin Restaurant, July 2010.

Published in the Huffington Post, July, 2010

Basquiat, who I knew for a few months in late 1982 and early 1983, made an indelible impression on me. It seems like a good time to share my recollections. The following essay, based on one I first wrote for my personal website in 1998, contains my most vivid memories.

A bit of background: when I met Jean I was 25, and had recently returned home to LA from Northern California, where I had earned a BA and an MA in Studio Art. Jean, who would have been 22, was a rising star on the New York art scene, spending time in Los Angeles preparing for his second exhibition at the Larry Gagosian Gallery.

When I met Jean-Michel Basquiat in the fall of 1982 he came to the door naked. I had been sent to Venice, California, where Jean was living in a former art gallery. Just a few days before I had been hired by art dealer Larry Gagosian, and had seen my first Basquiat Painting -- Skull, now in the Broad Collection -- at his gallery. Larry had explained to me that Jean needed some help around the studio.

Jean had probably just woken up -- it was early afternoon -- and led me his living space while wrapping himself in a towel.

He was living in a room that had only two pieces of furniture that I remember: a mattress with no box spring and a small TV set with rabbit ear antennae. As I later learned that he had once lived in a cardboard box in a New York park, the lack of furniture must have been a habit. I also found out later that he was paying Larry $2,500 a month in rent, and he certainly could have afforded furniture if he had wanted it.

The floor was covered with an amazing array of clutter: art history books, cassette tapes, art supplies, and clothing including lots of paint-spattered Armani suits that I later took to the dry cleaners in a plastic garbage bag. There were also drawings on the floor -- many with footprints on them -- and art supplies including oilsticks, paintbrushes and rollers. From time to time I also came across bags of marijuana, and wads of cash.

Jean-Michel never drove that I knew of -- an ancient Dodge that he had planned to use in LA had been stolen -- so I began to go over often, first to deliver the stretchers for him to paint on, and later to pick him up to run errands. Generally, he sat in my Toyota truck looking sullen behind dark glasses, speaking only to direct me to the next destination.

Jean was a big spender. When Madonna, just at the beginning of her celebrity, came from the East Coast to visit, I took him to the bank to get $5,000 cash. It was meant to be his pocket cash for the weekend. Another time, we walked into a local paint and hardware place and just cleaned out the art supply section. Jean-Michel, who cultivated a rasta street kid look, paid by tossing random piles of big bills on the counter so that the stunned cashier could do the counting. I also remember him buying a hundred dollars worth of Neutrogena soap at a Beverly Hills drug store.

One one errand I took him to the office of a doctor who was also an art collector. Jean was being treated for an STD and had arranged to pay for his treatment with drawings. On the way home he asked me to stop at a sandwich place he liked in Beverly Hills. He got out, and told me to just take a spin around the block and pick him up.

I got stuck in heavy traffic, and it took 20 minutes to get back. When I got there he didn't say a thing -- he was clutching a sandwich and glaring at me from the curb when I finally returned -- but three weeks later he walked up to me and gave me an utterly detailed description of how I should have taken certain back alley, and used a less busy street. He included street names and knew where I should have gone right, and where I should have gone left. Incidents like this began to show me how intense he was. Jean could remember details of all sorts and spew them out with real intensity at any moment. In many ways, that is what his art is about: intensely felt, but fragmented experience and knowledge.

Jean's heavy spending alarmed me. Once I told Jean that he needed to make investments, and that he ought to get a stockbroker so that if his career burned out he would have some money put away. He was furious, and immediately explained that there was absolutely no need for him to plan for the future. In his mind a star never had to worry about money, and I had insulted him by inadvertently suggesting that someday he his paintings wouldn't leap off the gallery walls.

After that I began to call him "Elvis," which was my way of kidding him about his out of control lifestyle. In response, he came up with "White Sambo Gringo," a jab back at me, his errand boy.

My life at that point was kind of like a twisted version of Driving Miss Daisy. I was a Stanford-educated, upper middle class white man, chauffeuring a younger African American art star who had never finished high school. With all respect to Tamra Davis, if I made a film about my experience of Basquiat it certainly wouldn't be called The Radiant Child, an oddly patronizing title borrowed from a 1981 essay on Basquiat by Rene Ricard. My film, Driving Mr. Basquiat, would be a very dark comedy about complex misunderstandings of race and class.

My other job, besides taking Jean out to buy art supplies and running him around town, was to build his stretcher bars and then prime them for his late night painting sessions that took place after he came home from the China Club. Among the canvasses I made were some triptychs, joined by Douglas fir 1" x 2"s and braced with plywood triangles made from shipping crates that had arrived at the Gagosian Gallery. One of these canvasses, which I had primed with black gesso, later became the "Horn Players" now in the Broad Collection. Working in my parents' garage I also made a series of large square canvasses, one of which became Hollywood Africans, now in the collection of the Whitney Museum.

Jean Michel, contrary to what you might think, absolutely did not consider himself a "Graffiti Artist." He had some friends like Ramelzee who did use that phrase to describe themselves, but Jean hated it. He once hung up on a woman graduate student who while interviewing him insisted that he was part of the Graffiti Art movement. He felt strongly that he was a fine artist, and his influences ranged from Leonardo da Vinci to Abstract Expressionists like Cy Twombly and Franz Kline. The influence of these and other artists is apparent in his best works.

One day when Jean was away from the studio, I saw a striking five foot square painting leaning against the doorway and decided I had to have it. Titled Future Science Versus the Man, I later learned that it had been in Jean's show at the Fun Gallery in 1982, and that he had brought it to LA where he added to it.

Science was an electric painting, a revenge fantasy meant to mock "white" history and progress as depicted in high school textbooks. It featured line drawings of warplanes, steamboats, Buffalo Bill Cody, a bug-eyed cowboy in a ten gallon hat, and an astronaut figure whose helmet enclosed a manic "Day of the Dead" skull. It also included words and phrases -- carefully printed in Jean's earnest block lettering -- including "Radium," "Egypt," and "Fraud 1/2."

Underneath a three-pointed crown, a signature Basquiat image going back to his days as the tagger SAMO, the phrase "Ten Gallon" was carefully lined out and then Xed out. All of this was set on a black and white background that an would have made a striking Abstract Expressionist painting, complete with drips. Jean had a way of making images completely his own, and maybe part of what he had in mind was to graffiti over a Franz Kline.

I made a deal to buy the painting with Larry, who must not have told Jean about my purchase. That would cause problems later.

I had some money saved, and since I was living at home and not paying rent, I could put most of my salary into payments. I came up with the total of $5,000 in about three months and took the painting home. My parents were mystified, but there we were, a white middle class family living on the west side of Los Angeles with a Basquiat in the downstairs bedroom. Whenever my parents, now in their eighties, see a Basquiat in a magazine it gets their attention. After recently seeing the designer Valentino posed with his Basquiat in a glossy magazine spread, they were anxious to point it out to me.

After I took the painting home Jean phoned me several times and insisted that I return it. He said that it should go to a "major collector." I wasn't part of the art crowd, and as a social nobody I apparently didn't even deserve to own one of his canvasses. Having grown up feeling excluded because of his race, Jean took a sadistic delight in turning exclusivity around and making it his own tool.

To convince me to let go of the painting Jean offered me a deal. "I have done only two portraits, one of the artist Francesco Clemente, and another of Andy Warhol," he told me. "I will do your portrait, and it will be my third, and I will give it to you." I fell for it, gave the painting back to Larry Gagosian and got my money back plus a $500 profit. I felt like a slick art dealer for about 5 minutes.

It wasn't uncommon for Jean to show hostility towards people who expressed interest in his work. One example of this -- which was related to me by another Gagosian employee -- took place when the wealthy art collector and MOCA founder Marcia Weisman came to visit Jean's studio. When she arrived at his studio, he took an immediate dislike to her. While she looked uncertainly at his work he became defensive and silent, and worked on an oilstick drawing on a very large piece of butcher paper.

The drawing, which showed a sort of frightening caveman holding a bone, was a kind of cartoon parody of savagery. As Marcia was getting ready to leave he added a penis and testicles to the image and later told a gallery employee that it was a depiction of Mrs. Weisman.

Jean had his big show in the Spring of 1983, with the painting I had returned on the front of the invitation. The opening was jammed, and he showed up very late and very stoned, listening to a Sony Walkman. I think he really couldn't handle social pressure. A few weeks later, he went back to New York and moved into a loft on Great Jones Street that he leased from Andy Warhol. When I got the job of cleaning up after him I found my portrait among the junk he had left behind. It was painted on one of the cheap canvasses we had bought one day at Standard Brands, and it had a splashed red circle -- my face as a happy face -- in the center.

On the bottom Jean had written my name "John Seed" in oilstick, followed by "White Sambo Gringo" with a red arrow pointing downwards. The arrow, of course, was pointing me down to Hell. Somehow, maybe by calling him "Elvis" or daring to buy one of his paintings, I had brought out his deepest hostility. The portrait had a bit of voodoo about it, and it made me uneasy enough that I never hung it on my wall.

A few weeks later, when I cleaned out his studio, I sent my portrait back to Jean's New York studio in a crate, along with some other things of his. I have never heard of it since and hope it went into a dumpster as soon as it got there. Jean's painting was meant as an insult, and it certainly gave me a jolt. If anything, it got me thinking about racial tension and in a way that nothing in my life ever had before.

As I had discovered, Jean-Michel could be pretty awful. He also could be very kind and sweet, and The Radiant Child apparently showcases that side of Jean's character. In my presence he was often very paranoid about the people surrounding him, and he certainly was right to be that way as so many people were using him in one way or another. At least one of the people who was around his studio stole drawings, and I tend to think that Jean liked to be stolen from: he could then amaze the thief by confronting them and knowing exactly what they had taken.

Putting aside the bad experiences of him, I have to say that he made a positive impression on me as an artist. He really had what I would call "second nature," which means that his art was utterly direct and in touch with deep emotions. I do think of his art as being poetic, and also as being about the alchemy of signs and symbols. He definitely made powerful art about the problems of race, and the sheer vitality of his ideas and imagery continues to dazzle me.

I was very fortunate to know him at the peak of his creativity, but also unfortunate to see his growing paranoia and distrust of those around him. He was a very troubled guy. When friends have asked me about him, I tell them that I truly believe that if he had ever been sober for an extended period, he would have needed psychiatric help. It is a shame that he never got that help: I understand that several people later did try. When I knew him a lot of money was being made; apparently nobody wanted to mess with the "magic," and drug use was a part of that.

People have also asked me if I regret selling my Basquiat painting. Honestly, it would be nice to have something worth millions of dollars, but I shudder when I think of the trouble that painting might have gotten me into over the years. I did see it again at the Basquiat Whitney retrospective in 1993. My wife offered to take my picture with it, but a hovering guard wouldn't allow it. I didn't bother to try and explain that it had once hung in my bedroom.

Across the street from where I teach there is a Red Robin restaurant. Over one of the booths is the now iconic Halsband photo of Jean-Michel and Warhol posed as prizefighters: feisty outsiders who both slugged their way to art world fame. When I take my family there for dinner, I often glance at the poster, and think about the sadness of it. There he is, the guy who was once a young art star, and an artistic genius, now a dead poster god like James Dean, or Elvis.

Of course, maybe that is exactly what he wanted all along.

Authors Note, December 16, 2010:

I was recently able to view "The Radiant Child" and I thought it was very powerful. In particular, I thought that interviews with Basquiat's friends and contemporaries were very insightful. I do think that the film could have said more about the tough issues of how Jean was exploited and how he in turn created his own problems.

Published in the Huffington Post, July, 2010