On Friday, May 29th, Christie's Hong Kong will auction 36 works of Asian Contemporary and Chinese 20th Century Art. Unless you pay close attention to Contemporary Asian Art you won't recognize the names of most of the artists included in the sale, such as Wang Yidong, Liao Chi Ch'un or Kim Dong Yoo.

There is, however, one name in the auction catalog very familiar to Westerners:

Andy Warhol.

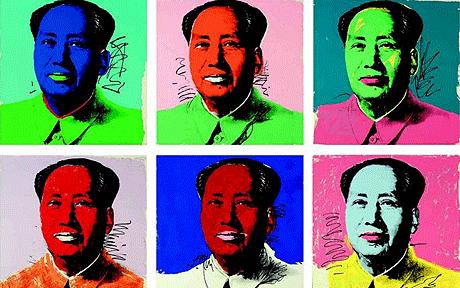

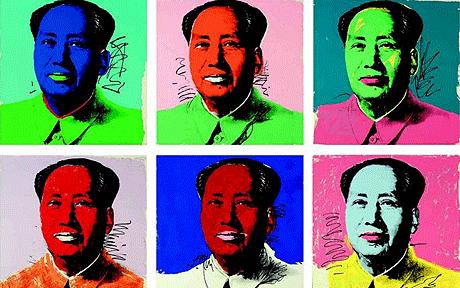

Six of the ten Warhol prints of Chairman Mao offered by Christie's Hong Kong

Christie's is offering the suite of 10 silkscreen prints by Warhol as a single auction lot, in hopes of demonstrating a "dialogue" between Asian artists and Warhol. Christie's has emphasized this notion with a seamlessly produced video in which Chinese speaking and English speaking experts take turns discussing the auction lots.

Of course there is more than a cultural exchange at stake. After all, Warhol understood better than any artist of his generation the alchemy that could turn a square of canvas or a sheet of paper into a luxury item worth piles of cash. What living artist or auction house wouldn't want to "dialogue" about that process?

The subject of the Warhol prints is none other than Chairman Mao, who had become a media figure after Richard Nixon's meeting with him in 1972. Warhol understood that while Mao's actual political influence was fading, he was still an "icon" ready to have his reputation sanitized and transformed into a subject for a Capitalist art audience. An expert on mass culture if there ever was one, Warhol sensed that the propaganda image of Mao that he appropriated for his "Mao" series was no different from the head shots of celebrities that he had lifted from American magazines and newspapers.

The idea of fame, he realized, crosses cultures very nicely. Warhol also recognized that fame is a form of forgetting who someone really is, a necessary ingredient in depicting Chairman Mao. In a sense, the Mao images were also elegiac: Pop Art funeral portraits that would look very nice next to a coffin.

At the invitation of a friend, Warhol visited China in 1982, also stopping in Hong Kong to create portraits of society figures there. China fascinated Warhol, and China remains fascinated with him. Since Warhol executed his works in a studio he called "The Factory" he would be interested to know that mass-produced reproductions of his works can now be cheaply purchased on the streets of Dafen, China, where the artists are not nearly as well paid as Andy was.

An image of Mao in the style of Warhol (lower left) seen in Dafen, China.

Art produced by painting factories, for sale in Dafen, China.

Photos of Dafen by James Fallows for "The Atlantic"

Dafen, just northeast of Hong Kong, has been called a kind of sweat shop for artists. It is one of three Chinese "painting villages" that produce roughly 60% of the world's oil paintings. Dafen paintings, of course, are meant mainly for WalMart shoppers, while Warhol paintings are a favorite of billionaires.

In 2006 Hong Kong billionaire Richard Lau paid $17.4 million dollars for a 81 by 61 inch Warhol silk-screen painting of Mao. To put the price Lau paid in perspective, the art factories in Dafen produced about 4 million paintings in 2006, netting $36 million US dollars. Since then prices for Warhol paintings have risen while China's painting factories have felt the effects of the recession in the West.

In the upcoming sale, Christies has estimated that the group of prints on paper, from an edition of 50, will bring as much as $647k (US dollars). Given the current craze for Warhol on the auction market, the actual sale price should easily top one million dollars. Since China now has more billionaires than any other nation, perhaps a few will be on the phone to Christies, bidding for the images of the man who famously purged China's liberal bourgeoisie during the "Cultural Revolution."

If Warhol had been living in China during that period, he would have been sent to the provinces to grow turnips. Of course, that would have only happened if he had been lucky enough to live.

Capitalism, which is certainly thriving in China while it struggles in the West, is apparently ready to support a generation of elite artists. Kim Dong Yoo, whose painting "Marilyn Monroe vs. Marilyn Monroe" will be featured in the Christie's sale, might just become the "Korean Andy Warhol." OK, that is a scary thought.

Andy Warhol, if he were alive, would not be surprised to see Western culture and art so popular in Asia. In 1982, when Warhol was asked what he thought about China not having a McDonald's he commented:

"Oh, but it will. "

Chairman Mao, if he were alive, would find all of the art at Christie's, Western and Asian alike, quite decadent. In his "Little Red Book" Mao reminds us that:

"A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture..."

Who will remember Mao's words on May 29th? If anyone does, they will likely appreciate that Warhol's 10 prints give them a playing card Mao: a smiling clown in a variety of candy colors. They are the comic ghosts of a once powerful man, mass produced and pencil-signed, by a Western artist who carefully studied the transient nature of power and fame.

Warhol, who died in 1987, will also be ghost at the auction. A powerful spectre, his ideas have retained their power better than Mao's. He knew that in 2010, China would have McDonalds, and that art would be made in factories. The revolution is over, for now.

Authors Note: The set of 10 Warhol prints sold for $856k US.

Links:

Christie's Video Seminar: Asian Contemporary Art in the Global Market

Workshop of the world, fine arts division by James Fallows

Warhol in China: A video clip

Remembering Mao's Victims

There is, however, one name in the auction catalog very familiar to Westerners:

Andy Warhol.

Christie's is offering the suite of 10 silkscreen prints by Warhol as a single auction lot, in hopes of demonstrating a "dialogue" between Asian artists and Warhol. Christie's has emphasized this notion with a seamlessly produced video in which Chinese speaking and English speaking experts take turns discussing the auction lots.

Of course there is more than a cultural exchange at stake. After all, Warhol understood better than any artist of his generation the alchemy that could turn a square of canvas or a sheet of paper into a luxury item worth piles of cash. What living artist or auction house wouldn't want to "dialogue" about that process?

The subject of the Warhol prints is none other than Chairman Mao, who had become a media figure after Richard Nixon's meeting with him in 1972. Warhol understood that while Mao's actual political influence was fading, he was still an "icon" ready to have his reputation sanitized and transformed into a subject for a Capitalist art audience. An expert on mass culture if there ever was one, Warhol sensed that the propaganda image of Mao that he appropriated for his "Mao" series was no different from the head shots of celebrities that he had lifted from American magazines and newspapers.

The idea of fame, he realized, crosses cultures very nicely. Warhol also recognized that fame is a form of forgetting who someone really is, a necessary ingredient in depicting Chairman Mao. In a sense, the Mao images were also elegiac: Pop Art funeral portraits that would look very nice next to a coffin.

At the invitation of a friend, Warhol visited China in 1982, also stopping in Hong Kong to create portraits of society figures there. China fascinated Warhol, and China remains fascinated with him. Since Warhol executed his works in a studio he called "The Factory" he would be interested to know that mass-produced reproductions of his works can now be cheaply purchased on the streets of Dafen, China, where the artists are not nearly as well paid as Andy was.

Dafen, just northeast of Hong Kong, has been called a kind of sweat shop for artists. It is one of three Chinese "painting villages" that produce roughly 60% of the world's oil paintings. Dafen paintings, of course, are meant mainly for WalMart shoppers, while Warhol paintings are a favorite of billionaires.

In 2006 Hong Kong billionaire Richard Lau paid $17.4 million dollars for a 81 by 61 inch Warhol silk-screen painting of Mao. To put the price Lau paid in perspective, the art factories in Dafen produced about 4 million paintings in 2006, netting $36 million US dollars. Since then prices for Warhol paintings have risen while China's painting factories have felt the effects of the recession in the West.

In the upcoming sale, Christies has estimated that the group of prints on paper, from an edition of 50, will bring as much as $647k (US dollars). Given the current craze for Warhol on the auction market, the actual sale price should easily top one million dollars. Since China now has more billionaires than any other nation, perhaps a few will be on the phone to Christies, bidding for the images of the man who famously purged China's liberal bourgeoisie during the "Cultural Revolution."

If Warhol had been living in China during that period, he would have been sent to the provinces to grow turnips. Of course, that would have only happened if he had been lucky enough to live.

Capitalism, which is certainly thriving in China while it struggles in the West, is apparently ready to support a generation of elite artists. Kim Dong Yoo, whose painting "Marilyn Monroe vs. Marilyn Monroe" will be featured in the Christie's sale, might just become the "Korean Andy Warhol." OK, that is a scary thought.

Andy Warhol, if he were alive, would not be surprised to see Western culture and art so popular in Asia. In 1982, when Warhol was asked what he thought about China not having a McDonald's he commented:

"Oh, but it will. "

Chairman Mao, if he were alive, would find all of the art at Christie's, Western and Asian alike, quite decadent. In his "Little Red Book" Mao reminds us that:

"A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture..."

Who will remember Mao's words on May 29th? If anyone does, they will likely appreciate that Warhol's 10 prints give them a playing card Mao: a smiling clown in a variety of candy colors. They are the comic ghosts of a once powerful man, mass produced and pencil-signed, by a Western artist who carefully studied the transient nature of power and fame.

Warhol, who died in 1987, will also be ghost at the auction. A powerful spectre, his ideas have retained their power better than Mao's. He knew that in 2010, China would have McDonalds, and that art would be made in factories. The revolution is over, for now.

Authors Note: The set of 10 Warhol prints sold for $856k US.