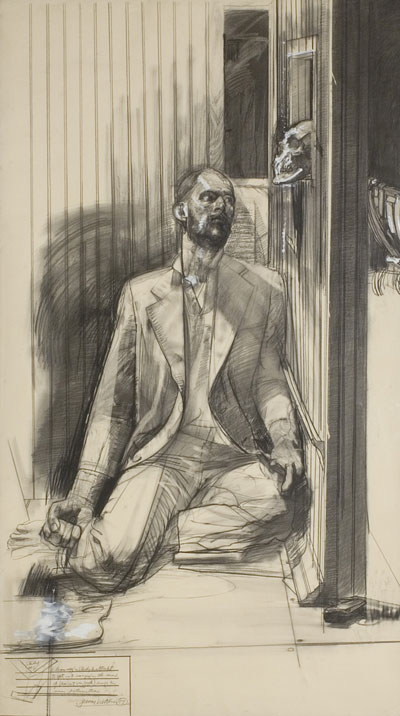

Mixed Media Drawing, 84 x 48 inches

"Let's not forget that small emotions are the great captains of our lives."

-- Vincent Van Gogh, in a letter to his brother Theo

The painter Jerome Witkin -- a vivid conversationalist -- tells a great story. "Painters are quiet in their studio," he comments, "so naturally they like to talk when they aren't working." Here is one particularly remarkable story that Witkin, 72, told me when I called him to talk about the exhibition of his paintings and drawings on view at Riverside City College through December 7th:

When I was a boy, newly interested in art, my mother took me to the Metropolitan Museum. We looked around the lobby, and when we discovered that there were no art classes being offered, my mother lost interest. I begged her, I wanted to see something, so she let me go upstairs alone. The Met then wasn't like it was now: it was like a big warehouse for scholars.

When I got to one dark room filled with paintings I heard a tapping sound, like a cane on the floor. I was fearful, somebody was coming towards me. This guy came up to me -- he had polished shoes -- he put his walking stick on my sternum and pushed me down.

He told me 'Dirty little boys like you should not be in museums like this.'

Years later I realized who that man was: James Rorimer the director of the museum."

When Witkin told me that story, I couldn't help but notice how passionately he was re-living the emotions of that moment as he told it. Certainly, it is a story he has told many times in the more than 60 years since the actual event, and stories re-told over time tend to lose accuracy over time. They become personal myths, and even the most objective man will forget, alter, or heighten the details of history.

In telling me the story, Witkin wasn't just telling me about something that actually happened. He was also telling me an emotional truth: that what he felt while growing up still has tremendous force. He is an outsider, still feeling the fragility of his place in the art world, and in the world in general. No wonder that empathy -- for victims of the Holocaust, for those suffering with AIDS, for the disenfranchised -- is the basis of many of his most compelling paintings.

Jerome Witkin, of course, isn't a documentary artist. His images, like his conversations, are deeply felt, and emotions matter more to him than objective facts. His intention is to be honest, but his honestly is about the passions of his life, and his empathy for others. Emotions are essential to Witkin: everything else is theater, and can and should be tweaked for dramatic effect.

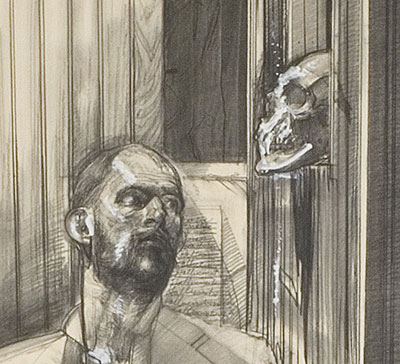

When I took a group of community college students to the RCC Quad Gallery to visit Witkin's show, several of them were spellbound by a large mixed-media drawing: "Vincent and Van Gogh and Death." It is a riveting drawing, and when I spoke with him Witkin told me about how he managed to "hit the bullseye" and give the work its emotional charge.

Van Gogh was a real man, and Witkin respects that: he has been poring over Van Gogh's letters and paying rapt attention to the realities of the man's life. Witkin reminded me, for example, that Van Gogh was the second "Vincent" born to his parents, and that he lived with the strangeness of having the same name as his dead younger brother.

Witkin staged the Van Gogh drawing in his studio, and the model who posed from him was a young man who felt right. A young man with "a red beard and intent eyes," Witkin mentioned to me that his model's real career was working with troubled teenagers. Sounding like a film director, Witkin related just what he had wanted the model to express for him:

"He (Vincent) is fighting his own sense of the weariness of life... questioning his purpose... always thinking about death."

Noting that "modeling is a performance" Witkin went on to tell that it "was a lucky day" when he created Van Gogh drawing. "His hands were so strong," he says of the model, who sprawled on the floor next to a 45 automatic in a structure that Witkin says is set up "a bit like a confessional." Looking in at his model, in the dark, constructed space engulfed in the light of his studio, Witkin managed to draft an image that is both hallucinatory and emotionally credible.

The real Van Gogh shot himself outside -- a botched job that left him lingering for days -- but Witkin's Van Gogh despairs indoors. In some ways, Witkin reminds me of the director Oliver Stone: he will tell you a story that rocks you to the core, but you have to remember that what you are looking at is "art." The skull that Witkin's "Van Gogh" peers at is real, but its purpose in being there is to make the painting a "vanitas" which is a tradition that references the history of art.

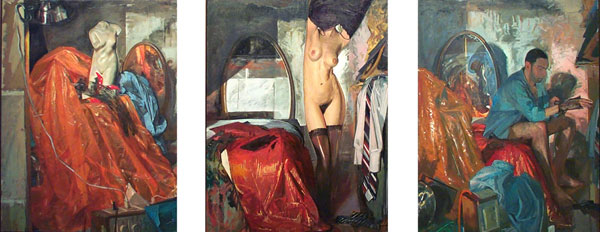

Oil on Canvas (Three Panels) 53 x 120 inches

Witkin's three part painting "Pensione Ichino" also references art history: its triptych format originally was developed for Late Medieval altarpieces. That said, the storyline of the "Pensione" canvasses is secular and deeply personal. It started, says Witkin, when a still-life setup sparked his memory. "Let's make a game of this," he thought as his ideas began to coalesce.

First came an orange plastic bag and a box, then a plaster cast of a woman's body, then a lace glove, all illuminated by a clamp lamp. The lace glove became a trigger that brought back a series of memories that in turn triggered the artist's memory of a brief love affair he had as a young man.

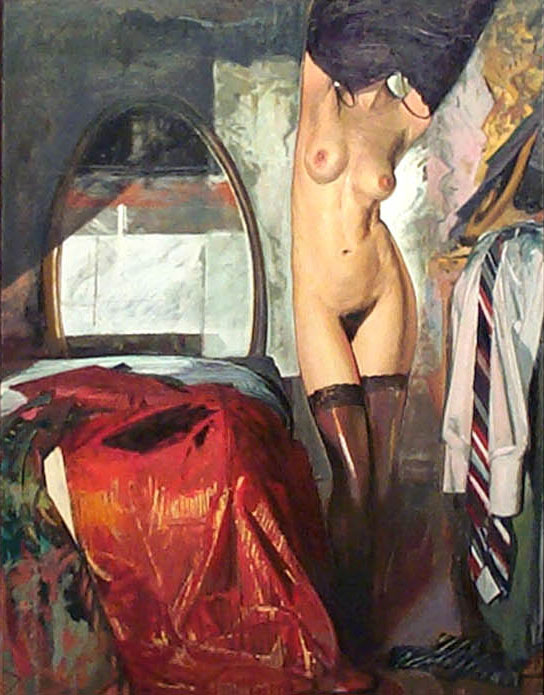

As a 20 year old Witkin won a Pulitzer fellowship to study in Europe, and in Florence he stayed in the Pensione of an Italian widow, "Old Lady Ichino." Her pensione had a great location -- right across from the Palazzo Pitti -- but the old lady wouldn't serve dinner to you unless you spoke Italian. Witkin also remembers that it was impossible to date Italian girls: their protective family members guarded them too closely. He did meet a lovely French photography student, "a hot deal," and in the second panel of "Pensione Ichino" she appears, a stunning apparition who reveals herself as she lifts a negligee over her head. She was, Wiktin remembers, a woman who enjoyed being looked at.

The artist is also present in the center panel, but only by implication. His shirt and tie hang on a chair in the painting, but Witkin is also very much there in the role of the artist/onlooker, conjuring up a real woman's memory amidst the studio props. Her sensuality and tangibility come across as a kind of paradox. "Witkin's subjects seem, if anything, overly immersed in the clutter of lived reality," says writer Joel Sheesley.

The love affair didn't last long, and after a short trip to Paris there was a breakup. Witkin remembers being miserable afterward, feeling the lows after the high of the affair. Love, and the emotions that go with it are another prevailing theme in Witkin's life and art. In 1986 he wrote: "Love and its folly; its non-being hurts me. Yet this is what I want to paint about. The wanting of love, the giving of it. Love as a healer. Without it one dries up."

In the third and final panel a young man -- a surrogate for the young Witkin -- slips the lace glove onto his hand. It is a moment of sensuality recalled and also an angry moment. When I spoke to Witkin he pointed out that the painting handling surrounding the figure was raw and somewhat violent. "Putting the hand through the glove," he explained, "has to do with destroying the memory, doing away with it." The memory of his lover is also suggested by the plaster torso, now just a reflection in the oval mirror.

"Pensione Ichino" is about the evocation of a memory, and ultimately about the artist's need to control and even destroy that memory. The emotions he evokes in the process are strong and specific: so strong that it is tempting to call Witkin an Expressionist. The problem with that label is that Witkin has much more control of his emotional range -- and his drafting -- than most Expressionist artists. His effects and images are refined and calculated, and if anything he thinks more like a playwright than a painter. Calling "Pensione Ichino" a "drama in three acts" isn't far off the mark.

Syracuse University is now organizing a 40 year retrospective of Witkin's work, tentatively slated to open in 2012. The "dirty little boy" who was once pushed to the floor of the Metropolitan Museum by its director is now seen as a leading representational painter. Critic Donald Kuspit says "Indeed, there are few painters working today who have as consummate and vivid a sense of the human drama, in all its personal and social complexity, as Witkin does."

At one point in our conversation Witkin mentioned to me that a few years back he received an award from the director of the Metropolitan -- not the one who had confronted him, but a later one -- and that he managed to control himself and not tell the director to "Fuck off." Listening, I wasn't sure if I really believed everything Witkin had told me about the incident, but I had become totally convinced of his brilliance as a storyteller. His art is a masterful blend of history, memory and fantasy.

The forty minutes we spent on the phone went very quickly, and Witkin gave me a great deal to think about. Looking over my notes later, one comment stood out for me. "When you make a work of art," Witkin told me, "you don't know where it will end up." Coming from a man who understands that emotions drive our lives, our institutions and ultimately, history past and present, I took that thought to heart.