In 1988, artist John Nava, who had just turned 40, told William Wilson of the Los Angeles Times that he was "looking for a way to paint the figure seriously in the 20th Century." Twenty-two years later, a decade into the 21st century, Nava is indeed creating figurative art of great seriousness, but there is a twist. His monumental depiction of a procession of 21 life-sized figures, now on view at USC's new Tutor Campus Center isn't a painting: it is a tapestry.

Nava's engagement in tapestry began in 1999 when he was commissioned to create 3 cycles of tapestries for the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles. Tapestry was initially chosen for acoustic reasons, but once the project got rolling Nava found other advantages. With a tight 3 year timeline he could paint figure studies, have them composed and compiled in Photoshop and then email the images to Belgium, where digital technology facilitated rapid production of the actual tapestries. Nava had also discovered a medium that was both sensuous and at the same time able to render subtle detail.

Besides alerting Nava to tapestry as a medium, the cathedral project connected him with a 2,000 year lineage of traditions and values surrounding the creation of religious art. Depicting the figure in a "serious" way was now more than just a goal: it was a requirement. Challenged to create timeless images for a contemporary audience, Nava had to answer a profound question. How could he express the ancient idea of sainthood and do so in a way that made sense for the 21st century?

His answer, three cycles of images portraying 135 saints and "blesseds" -- females and males of all ages, races, occupations and vocations from all over the world -- expresses to the cathedral's diverse visitors the idea that "a saint could look like me." It was a powerful theme, and it continues to resonate in Nava's recent works, both religious and secular. Nava says that "humanity, consolation and redemption" are the most important themes of his commissioned works.

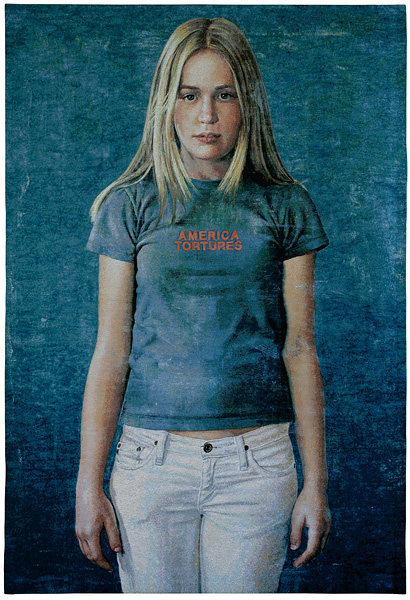

After completing the cathedral project in 2003, Nava continued to work with tapestry. His 2006 exhibition at Sullivan-Goss Gallery in Santa Barbara, titled "Neo-Icons" -- a title meant as a rebuke to "Neo-Cons" -- featured tapestries and paintings of fresh-faced adolescent Americans.

Presented in a straight-forward manner designed to emphasize their innocence, each young man and woman depicted wears a t-shirt with a slogan decrying America's post 9/11 policies and actions. In the accompanying catalog essay Mr. Nava did not mince words when describing what he viewed as the "breathtaking arrogance, exceeded only by stunning incompetence" of the Bush/Cheney administration. One memorable tapestry from the show is of a young woman with straight blonde hair who faces the viewer with some apparent shyness. Her blue t-shirt says, simply "America Tortures."

After the gallery received nearly 100 phone calls, some threatening, Mr. Nava attended the opening with a bodyguard. He also caught the attention of Dr. Laura Schlessinger, who mentioned the exhibition in her weekly Santa Barbara newspaper column, slamming Nava for being part of an "anti-democratic" force that she characterized as "the greatest danger to world peace ever."

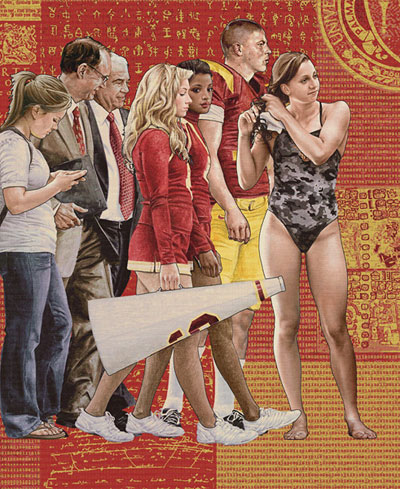

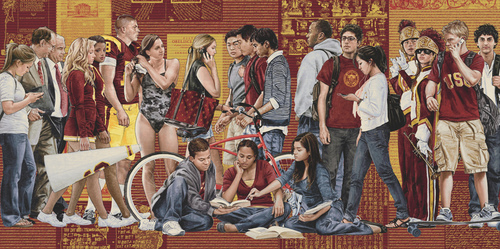

Ironically, the outcry caused by "Neo-Icons" points out one of Nava's greatest strengths as an artist, a strength that is readily apparent in his 22 foot square "Trojan Family Tapestry." Deeply knowledgeable about history, Nava takes the "long view" of art and history, but doesn't shy away from the particulars that define individuality and temporality. His USC tapestry features a procession of figures that emulates the reliefs of the Roman Ara Pacis of 80 AD, but at the same time features an image of a young man distractedly talking on his cellphone.

Each of the tapestry's 21 figures is an individual portrait of a member of the USC campus community; USC President Emeritus Steven Sample, alumni donor Ron Tutor, swimmer Rebecca Soni, and football player David Buehler, and 17 others. Each is beautifully individualized, but at the same time part of a flow that joins them together in time.

Woven near Bruges, Belgium, using cotton, wool and silk fibers, the tapestry also features a rich ground that Nava calls a "mosaic of texts." Among the included texts -- all taken from USC Library holdings -- are a 13th century Koran, a Mayan codice, an 1807 Japanese manuscript on the life of fisherman, and a page from the Nuremberg Chronicles. All of those texts, and many others, float in a field of binary code.

The wide range of historical and aesthetic sources quoted by the work create a kind of tension, something the artist fully intended. As Selma Holo, the Director of the USC Fisher Museum of Art points out, the tapestry makes "a point about the tension between the universal language of art and the moment." On the one hand, it seems fair to call Nava a traditionalist, but that assumption weakens if one considers his knack for contemporaneous details and images, and his fusion of traditional and new media. "Nava's art is always evolving and a unique blend of opposites; age-old tradition and cutting-edge technology," says his friend and fellow artist Jon Swihart.

The use of tapestry as a medium also adds to the feeling of timelessness that adds weight to the more particular and documentary aspects of the work. As Holo points out, most contemporary tapestries are reproductive, meaning that they are copies of recognizable works. A case in point would be the tapestry of Picasso's "Guernica" at the United Nations building in New York, commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller 16 years after Picasso unveiled the original mural. Nava, on the other hand, sees tapestry as a powerful medium for original contemporary works. That makes him one of a handful of artists re-inventing a medium that most art historians feel died 400 years ago.

Dr. Steven Sample, who recently retired after 20 years as the President of USC, is seen on the left side of the tapestry, walking alongside alumni donor Ron Tutor, taking part in the procession the way the donors might have in a medieval religious image. Sample, who Selma Holo credits with leading USC into the ranks of America's finest academic institutions, was standing in front of the installed tapestry recently when Nava asked him if he recognized himself.

"I recognize the University" Sample replied: a wonderful validation of Nava's achievement.

John Nava has done something very rare in the field of contemporary art, offering a timeless portrayal of individuals in a democracy, moving forward together, bound to each other by mutual respect. It is worth noting that in the "Trojan Family Tapestry" the college president and the donor follow the students, acknowledging that they are the ones who will take this particular moment of time into the future.

John Nava will be speaking at an "Art Grand Opening" at USC's Tutor Campus Center on the evening of September 30th.

Q and A with John Nava:

JS: Can you tell me just a bit about the influences behind your USC tapestry?

JN: For me the solution to depicting a "world" -- or perhaps more precisely a culture or human/societal milieu -- was the image of the frieze. The frieze of figures in passage within an environment was used by the Egyptians, famously by the Greeks in the Parthenon frieze and so on. I was particularly thinking about the frescoes of Piero della Francesca in Arezzo. In all these examples there is a certain formal, non-documentary realist aspect to the image. It has a "pageant" quality and is meant to be read, not as a "slice of life" scene but as a metaphor about the processes and timeless meaning of the life of the subject society.

At USC I was trying to show not only the grand, over-arching role of the university in civilization but also the ongoing process of perennial engagement and interaction with generations of students as they move through academe. Hence the juxtaposition of the students and the field of texts.

JS: You told the USC news service that you want the tapestry to reflect the "interior preoccupations and attitudes typical of all generations of students." Can you expand on that?

JN: I always think that the situation of students is hard to surpass -- they're young, beautiful and bright and get spend their time studying really grand and profound matters with fantastic scholars. However, as I remember from my days teaching, the kids themselves are not walking around in blissful awe but are, instead, wrapped up in all the adventures of this amazing period in their own lives with all the soap opera that often goes with it. So I wanted to get this quality as opposed to depicting them as bunch solemn medieval monks in procession weighted down by their intellectual labors.

JS: Did you also try to say anything particular about the current generation of students?

JN: I think that to make something "timeless" it is, perhaps paradoxically, necessary to be very observant and humanly true in the images of the figures. When we see a face in a toga on a wall in Pompey or another in a robe in a Flemish painting and it has that human truth we recognize it immediately and the ages that separate us from that work dissolve. And that recognition gives the image gravity and reality --we get it and we believe it.

So if I had done a similar group of figures from USC in the 1930's there would have been many of the same types peculiar to that school -- the football player, the cheerleaders, the band members and the kids in casual dress of time. But they would not have looked like they look now -- our time puts its own unique stamp on their appearance just as the classic texts they are seen with is saturated with binary code so typical of our age. But if the portraits were good and not stylized in some way to make them seem dated we would still connect with those figures and hopefully recognize them as a reflection of ourselves.