Jon Swihart, a Santa Monica artist known for his highly refined figurative paintings, has a genuine obsession with the artist Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904). In revering Gerome, a largely forgotten 19th century French academician, Swihart has chosen an obscure master who most contemporary critics feel was a reactionary of the worst sort. As Swihart's friend and fellow artist Peter Zokosky notes: "When Jon discovered Gerome, he couldn't have found a more out-of-fashion artist, so you know the connection has to be real."

In his review of "The Spectacular Art of Jean-Leon Gerome," on view at the Getty Center in Los Angeles through September 20th, LA Times critic Christopher Knight casts Gerome as a wrong-headed artist, a lingering academician in a world tilting towards modernism who "didn't have a clue."

Knight, who discounts the illusionism and technical virtuosity that made Gerome famous in his own time goes on to remind his readers that "From Manet to Cezanne, every artist we revere today was on the other side of Gerome's fight." Gerome was indeed a vehement opponent of the Impressionists who refused to attend a memorial for Manet in 1884. After all, Gerome felt that Manet, a pioneering Impressionist, had "...chosen to be the apostle of decadent fashion, the art of the fragment..."

Just how did Swihart, a Californian born 50 years after Gerome's death, manage to choose such an iron-clad reactionary as his artistic role model? The answer begins with a tragedy.

Jon Swihart's parents were both Sunday painters, so art was around him from an early age. He was part of a happy family until the late 1960s when his mother became seriously ill. When she died in 1970 the family was "destroyed" and in short order Swihart's two older brothers were drafted into military service. What had once been a warm family home felt deserted and sad. Swihart, then 15, began to spend many hours in his room alone, and at the Santa Monica library where he lost himself in art books. Art gave him a feeling of being connected to his mother -- and to his grieving father -- and provided a distraction he desperately needed.

The images that attracted him most were by 18th and 19th century artists. JMW Turner and Claude Lorrain were briefly favorites, but one day a catalog of an exhibition by Gerome appeared. How the catalog, published in 1972 by the Dayton Art Institute, made its way into the Santa Monica library is something Swihart wonders about to this day. From the frontispiece on he was hooked: Gerome's remote, burnished images engaged him, spoke to him. The artist's subjects -- slave auctions, Muezzins calling from minarets, nude statues coming to life to kiss their creators, triumphant gladiators -- were heady stuff for a teenager from Santa Monica.

His art was "...different, exotic, strange, photographic, perverse," Swihart recalls. Those very qualities had once made Gerome and his equally popular peer Bouguereau the best known, and wealthiest artists in France. The two academicians, stars of state sanctioned salons, were enemies of the avant-garde, emboldened by public acclaim and financial success. Bouguereau, who the modernist Matisse famously studied with, and despised, once bragged that "Every time I piss I lose five francs."

Remarks like that helped put the nails in the art historical coffins of the late 19th century academics, who were seen a few decades later as colonialist pimps, chauvinists, and aristocratic lackeys. The Impressionists, once outcasts, became the heroes of the middle-class whose lives they celebrated with glowing patches of complimentary color. Both characterizations were flawed, but over time they stuck.

Gerome, whose father-in-law art dealer Adolphe Goupil was a marketing genius, became wealthy by having reproductions of his work mass marketed. During his lifetime Gerome's works were printed in every size, from playing card size on up, and for the right price he even made copies of his own works. Over time the overexposure of Gerome's work has been one of the factors in the decline of his reputation with critics and art historians. One recent commentator, who must have known something about Gerome's marketing, but not much about his art, quipped that "The similarities to (Thomas) Kinkade especially are almost endless."

At the time he discovered the Gerome, Jon Swihart certainly had no concerns about the man's tainted place in art history: he was a figure to be idolized. Poring over and re-reading the Gerome catalog endless times, he noticed that one of the authors was a "Gerald Ackerman." He was shocked to find that Mr. Ackerman was professor of art history at Pomona College, just an hour away. Mustering up his courage he called Ackerman on the phone, and that phone call initiated a 38 year friendship based on a shared fascination.

When he entered Cal State Northridge, Swihart took his first art classes and found only one instructor, a photo-realist named Bruce Everett, who was sympathetic to his singular approach. Swihart, was already an unorthodox figure, who quietly noted that most other students and many of the instructors "simply couldn't draw." Abstract painting was the academy of the moment.

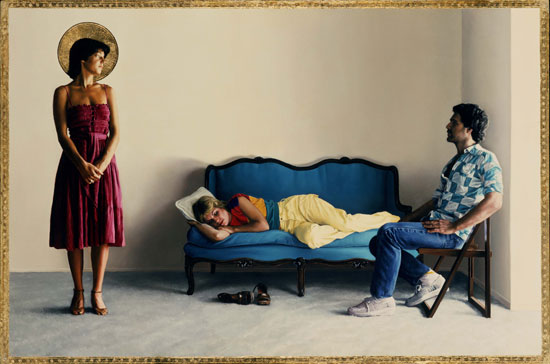

Everett watched Swihart, a shy student at first, develop a series of paintings based on rituals and situations gleaned from Renaissance paintings. Often mistakenly viewed as religious paintings, Swihart's Northridge works helped him make friends with other students who often posed for him. They also allowed him to display both his wry sense of humor and an agnostic fascination with the drawing power of rites and religious symbolism.

As Bruce Everett recalls, after a certain point he had little left to teach Swihart, who was already very much a connoisseur, a man charting his own course. After completing college, earning a BA in 1979 and an MA in 1982, both in art, Swihart was moving against the grain of the contemporary art world. Despite his diplomas he was to some degree a self-taught artist whose most important lessons had come from conversations with a living art historian and a dead French academician.

In 1988 Swihart was selected to live and work at Claude Monet's newly restored home and gardens in Giverny, France. Spending nine months in France, which Swihart recalls as the "greatest period of his life," he spent his free time "Geromeing," seeking out every trace of the artist he could find. On his first day in Paris, Swihart visited Gerome's tomb in the Montmartre Cemetary.

There, he found that the cast of "Sorrow," a grieving figure that Gerome had made in response to the death of his son Jean in 1891 had been removed from the grave site. It had been covered with pigeon shit after an overpass had been erected overhead some years before. He also worked hard to locate the site of Gerome's studio, which had been destroyed in a World War II bombing raid. Pigeon shit, bombing raids and hostile critics, it turns out, had all taken their toll on the legacy of the artist Swihart so deeply admired.

There is tremendous irony in the fact that an artist living in Monet's home spent so much time researching the life of the "sword and sandals" painter who had scorned Impressionism. The paintings Swihart made while in France -- sober, precise landscapes with leaden skies -- have none of the vivid colors or excited brushwork that living in Monet's home might have inspired in another artist. During his time in France, and on a second trip five years later, Swihart tracked down and traded stories with the descendants of Gerome's three daughters, located and took photos of his homes, and amassed a "treasure trove" of material.

Today, Jon Swihart lives and paints in the same home that he grew up in, surrounded by his Gerome treasure trove which now includes 3 oils, 13 drawings, 3 bronzes, 65 or so letters, and a number of original photos of the artist. Also on display at Swihart's home -- which feels like a boutique museum -- are his own works, a painting by Gerome's son-in-law Aime Morot, an oil by Ernest Meissonier, and a bust of Gerome by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. A partial list of other items on display -- antique casts, Russian icons, Gladiator helmets and a reproduction of a 3.2 million year old human skull -- gives some idea of Swihart's collecting impulses.

Swihart has also been collecting friends. Once a month his backyard fills up with artists, art historians and anyone else who cares to come, for a potluck barbeque followed by a guest lecture by one of Jon's art world friends. Sometimes there is entertainment as well. Towards the end of one potluck a few years ago a group of fire-spitters imported from the Venice Boardwalk literally stopped traffic in front of Swihart's house. It was a spectacle that Gerome would have admired.

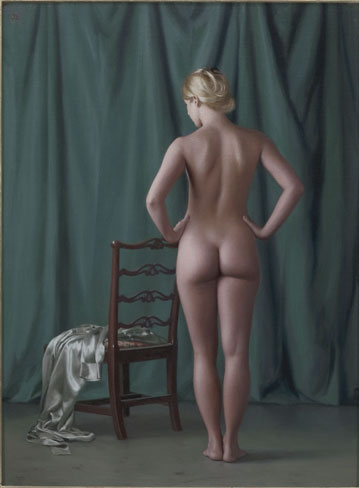

He also would have admired Swihart's recent paintings: callipygian female nudes, with no traces of visible brushwork. They are the artistic descendants of the statue who came to life in Gerome's "Pygmalion" and the alabaster-skinned women who stood on the block in his "Slave Auctions." Swihart, over time, has been able to create figures of jaw-dropping smoothness that have a hint of immortality about them.

Swihart, modestly enough, is careful to state that he is "not even close" to his master, and is reticent to compare his abilities to Gerome's.

On August 21st, Jon and his friends will gather at his home to honor Gerald Ackerman who will be celebrating his 82nd birthday. Ackerman, who is credited by the curators of the Getty Gerome exhibition with "nearly single-handedly" keeping Gerome scholarship alive for the past 30 years, will be speaking about the Getty exhibition and about Gerome's work. Jon Swihart, who has seen the show at the Getty seven times already, says it is "tremendous" and that nearly every work on display shows the artist at his best.

At the Getty bookstore, "Reconsidering Gerome," a book of ten essays meant to help scrape the critical pigeon shit off of Gerome's reputation, is on sale for $27.50. However, the store will not be carrying a unique item that Jon Swihart says is the very first thing he would grab if his house caught on fire.

It is an uncanny object: A Gerome "Action Figure" created by Peter Zokosky as a recent birthday gift for Jon Swihart. If art history had gone differently, maybe factories in China would be cranking these dolls out, and aspiring young artists across the world would be playing with them, setting them up at plastic easels and offering them tiny baguettes and molded wine bottles. It would be a world where prodigies would be called "Mini-Geromes," not "Mini-Monets."

Swihart says that when the figure was first presented to him, he freaked out a bit: he had a Pygmalion moment when for a split second the figure seemed almost alive. There, staring at him from behind a cellophane window was the reincarnation of his "master," the man who in artistic terms gave him "everything."

As strange as it sounds, Gerome really is a living presence in Swihart's life. There simply wasn't anyone alive who could teach him what he needed to know. "Jon's a great painter," says Peter Zokosky, "and he learned most of what he knows from Gerome." Somehow, across the barriers of time and public opinion, they reached out to each other and started a very intense conversation that isn't over yet.

Having that connection has remained essential, giving Swihart a critical anchor while the art world hems and haws, annointing new idols and dispensing with previous ones. Peter Zokosky puts it this way:"The academy never goes away, it just shifts, and there's always an approved academic style: today the academy loves Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons."

Towards the end of his career Gerome softened his views on Impressionism, stating that "...it was not so bad as I thought". Perhaps Gerome wasn't so bad as we thought either. Just the printed images of his paintings on a catalog page were enough to soften a young man's grief and lead him towards his future.