Painter Leonard Koscianski turned 58 in April, and a fair amount of water has flowed under the bridge of his life. There have been losses along the way, including a son and a first marriage, but his art is burning brightly. When his solo exhibition, which Koscianski feels is his "most visceral show ever," opens at OK Harris Works of Art on September 11th he will unveil a suite of paintings that have the clarity of waking nightmares.

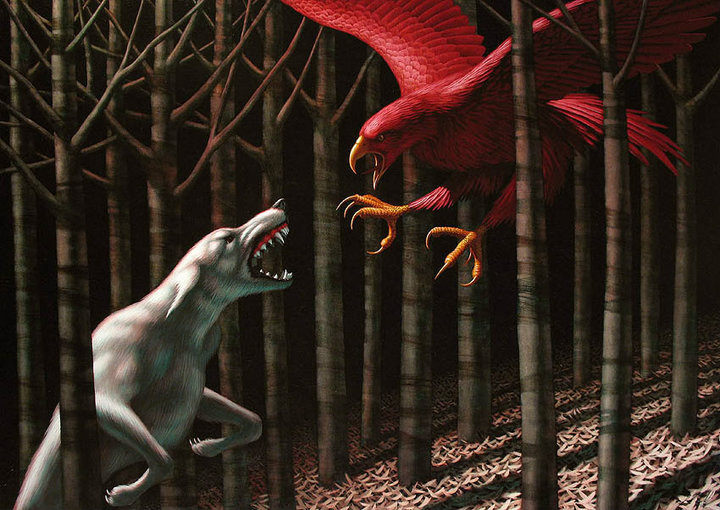

Featuring dogs and birds that clash in a nocturnal landscape, the paintings are fierce, polished and intense. Intensity, a family trait, is the engine that drives Koscianski's life and art. Raised by a father who was a self-employed attorney and a mother who became an energetic fashion designer late in life, Koscianski witnessed the power of drive early on.

With his three surviving children now young adults, the energy Leonard used to pour into parenting now goes elsewhere. He starts each day at dawn, taking his coonhound "Scout" on a 5 mile run through the streets of Annapolis. Painting begins by 9, followed by lunch at 1:30. Amazingly, his lunch -- a peanut butter sandwich, potato chips and an apple -- has not varied in 30 years.

At 2:15 Koscianski is back in the studio, refreshed and ready to exert all the physical and mental energy he can muster, battling with his paintings into the evening. When I asked Koscianski about his palette and color choices he told me that he "sweats color." No wonder his finished paintings gleam with ferocity, a quality that the artist wants his viewers to recognize, fear and value.

"Fierceness is in all of us," he observes, "It erupts from the depths of our animal brain. As we mature we learn to control it... when uncontrolled it can destroy us. Reaching any difficult goal requires a certain amount of inner fierceness."

In an effort to channel his own ferocity Koscianski has built a career as an iconoclastic artist, guarding the integrity of his art while attempting to stifle his own ego. Seen another way, Koscianski is a very civilized man with a highly developed wariness about the potential for violence in both the real world and in the inner world of his imagination. The studio is where he struggles to forge a balance between the two.

As an undergraduate, Koscianski first studied art history and architecture. The architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller was one memorable professor; art historian Gabriel Weisberg, a specialist in 19th century French art, was another. Later, as an art student at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Koscianski was hired by Museum Director Sherman Lee to paint copies of old masters on Sunday afternoons. He made 17 copies this way, an invaluable experience.

The experience of copying old masters, and the influence of two books, Beyond Modern Sculpture and The Structure of Art, both by Jack Burnham, rescued him from what he calls "the clutches of doctrinaire Modernism."

By the time he found himself in the MFA program in painting at UC Davis, Koscianski already knew that his heroes were mainly 19th century artists. The Swiss symbolist Arnold Bocklin, the oddball Romantic Henry Fuseli, and the sculptor Alfred Bayre -- who famously depicted a jaguar devouring a hare -- were among those who fascinated him. Clash and conflict is also a feature of Kosacianski's all time favorite painting: Raphael's "St. George and the Dragon," in Washington's National Gallery.

While at Davis, Koscianski served as a teaching assistant for the famously good-natured Wayne Thiebaud. Following Thiebaud's lead, Koscianski made vague attempts at "Pop" art, but the style didn't suit him.

"I made still life paintings that were strongly influenced by him," Koscianski recalls, "but his were light and humorous while mine were dark and threatening."

Koscianski did paint one landscape painting in grad school, but it wasn't until he was teaching at the University of Tennessee that animals began to appear. Dogs, pigs and sheep began to "people" his landscapes from that era, and dogs especially have been recurring images ever since. The settings tended to be the edge of nature where it collides with civilization, specifically suburban civilization. Growing up in Cleveland, "a town of small suburban houses," had left lingering stage sets in Koscianski's mind.

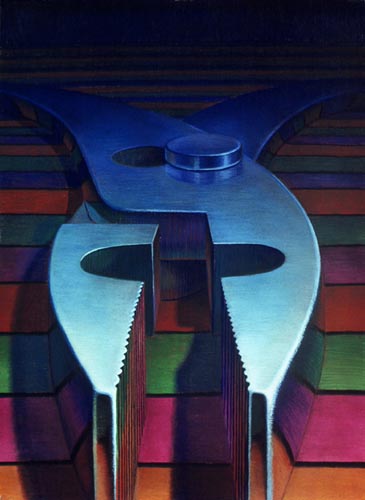

Private Collection

In "Suburbia," a 2001 oil, a stray dog with its head lowered approaches a solitary figure, distracted the by the light of a television. Although the painting carries potentially straight-forward symbolism -- animal violence can find you when you aren't looking -- Koscianski has always made it clear that he doesn't give his paintings specific meanings. That job belongs to the viewer.

"You project your experience," Koscianski insists, the meaning of his paintings is "...never meant to be fixed."

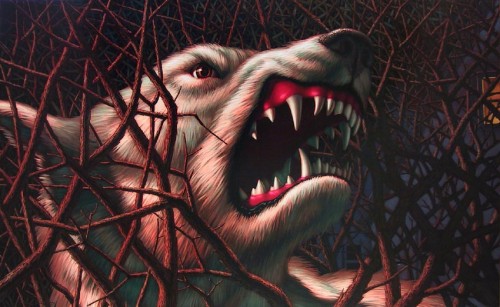

As a result, viewers have to cope with the moral ambiguity of Koscianski's imagery. Dogs, so often seen as images of loyalty -- man's best friend -- are feral and bloodthirsty in his work. Similarly, the birds of prey in his recent paintings might strike some as a militant, terrifying images, while others would recognize them as the mascot of their high school football team. Standing in front of one of Koscianski's animal paintings tends to bring up the question of whether the viewer should feel attacked or defended.

Private Collection

Not surprisingly, Koscianski has been told that the creatures in his paintings have reminded people of their attorneys, or their former spouses. Commenting on the fact that his New York exhibition will open on September 11th, he acknowledges that his works will likely be seen as alluding to the "fierceness" of the terrorists attacks 9 years before, and to the wars that followed. It is a connection he is aware of, but not one that he specifically set out to reference.

Courtesy of OK Harris Works of Art

The tensions of Koscianski's paintings are the same tensions that the Romantic artists he admires also struggled with. He seems to have taken to heart William Blake's famous advice to young artists: "Seek out those images that constitute the wild..." When Blake gave that advice, he was asking artists to search for the grand forces that had upset the appearance of order that earlier culture had struggled to erect. Those forces, as the Romantics and those who followed them increasingly argued, came from deep inside.

Leonard Koscianski, an artist who read stories to his children every night while they were growing up, understands that the mind is where history is made. His job, as he sees it, is to remind us of the struggles that go on there. In Koscianski's mind the dog and the bird both seem quite fierce, but they are evenly matched.