Mari Lyons turned 75 last week. She has been painting for more than 60 years, but says that she is still struggling to be free of certain habits. "In my studio I have paintings that go back to the 50's," Lyons explains. "I can't help but come to painting with an accumulation: you can never get rid of yourself."

It is a very modest self-assessment by an artist who, in truth, creates paintings that radiate a constant joy of discovery. "Almost everything in Ms. Lyons's paintings is animated, excited, and alive," says critic Lance Esplund.

Praise from friends doesn't seem to affect Lyons, who is unassuming in general. Although she paints passionately, she knows her own limits well. Writing about her current series "Sunsets/Hillsides" she says "I have worked on this motif on and off for nearly a decade and I cannot grasp its infinite complexities."

One of Lyons's favorite quotes comes from Ralph Waldo Emerson: "Every object rightly seen unlocks a quality of the soul" Lately, she has been looking out the three windows of her Woodstock studio, trying to "unlock" the secrets of her hillside. Even though she feels that her view isn't monumental -- "a modest forest of ash, hemlock, and pine" -- she is devoted to it. "Its just as hard and impossible to know a hillside as it is a person," she observes wisely.

"Sunsets/Hillsides" is about her meditation on the metaphorical potential of the landscape, and also about a kind of conversation with Paul Cezanne, an artist she discovered when she was 20. Of course, by that time she had already been painting for more than 7 years, and had more than a passing acquaintance with modern art and artists. Her education as an artist started early and has never really ended.

By age 13 her father was taking her Saturday drawing classes at the the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. "Still and Rothko were there," Lyons recalls, but she mainly remembers an encouraging instructor named William Brown. She drew the model for 4 to 5 hours at a stretch, a remarkable thing for a 13 year old to be doing, especially in the late 40's.

At 15 Lyons took a summer painting class at Mills College taught by Max Beckmann, the German Expressionist who came to teach in the US after WW II. "It was a motley group,"Lyons remembers,"older women with canvas boards, some not very serious painters, and then one or two serious students," one of whom was the Bay Area artist Nathan Oliveira.

Beckmann, who spoke little English, barely noticed Lyons -- "Gut Kinder" was the only comment she remembers -- but he and his art made an indelible impression on her. When he showed his works to the class at the end of the term the symbolism escaped her, but the power and intensity of the works, their "truth," was unforgettable.

The following summer Lyons studied with Fletcher Martin, a representational artist who had been an artist/correspondent for Life Magazine. Martin was very encouraging, telling Lyons that she was "The best student he ever had." Later, he gave her a more patronizing compliment: Lyons remembers bristling when he called her "A significant woman painter."

When she attended Bard College, 90 miles north of New York, Lyons studied with Stefan Hirsch, a German emigre who had once created a controversial WPA mural depicting an allegorical figure of "Justice" as being mixed-race. She also took classes with Louis Schanker -- an abstract printmaker once called a "radical among radicals" -- and Ludwig Sander, an abstract artist friendly with Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline.

Lyons also spent six or seven months in Paris where she studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere, at L'Atelier Fernand Leger, and also at the Atelier 17 of famed painter/printmaker Stanley William Hayter. Although postwar Paris and its great museums made a great impression on her, Lyons recounts that she often felt "intimidated and lonely" in Europe.

After receiving an MFA in painting from Cranbrook in l958, Lyons, now married, moved to Ann Arbor, where her husband Nick was finishing a PhD. In four and a half years the couple had four children -- the first is Paul, named after Paul Cezanne -- but somehow Mari managed to have a one woman show at the Forsythe Gallery. After moving to New York City in 1961 Mari kept a studio in the corner of her bedroom, and regularly drew from the model with upper west-side artist friends.

It has been a rich, busy life, and Lyons has been the subject of over a dozen one-person shows in New York alone. "A lot happened in the intervening years," Lyons reflects, "but I always painted." That is an understatement: Lyons's eccentric and vivid depictions of nudes, cityscapes, landscapes, still-lives, and interiors have caused critic Jed Perl to remark that she "has staked her claim as the complete painter, the master of every genre."

Since her husband Nick sold his publishing business, Lyons has been spending more time in Woodstock, where the landscape motif has called to her off and on. Writing in the New Republic about Lyon's 2008 exhibition, Jed Perl noted the "unabashed color," and "buttery seduction" of her landscape canvases. He felt that the show was "more than anything else, about color becoming light."

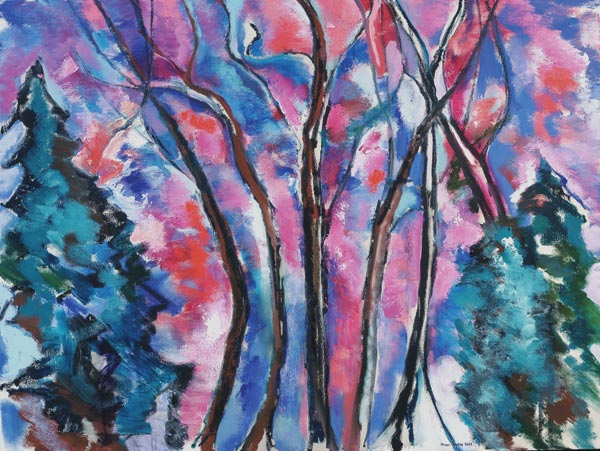

The landscapes of the "Sunsets/Hillsides" certainly are about light, and also about joy. "When you are connected, you feel a joy in seizing some aspect of the real world," Lyons says. Using color in "patch-like juxtapositions, derived from Cezanne's color modulations," her painting "Exploding Cherry Tree" achieves an exuberance tempered by a net-like interlace of dark strokes.

Although she has consistently worked as a representational painter, Lyons doesn't mind letting her work veer towards abstraction. "The question of whether they are realistic or abstract is irrelevant," she says. One of the values she seems to have absorbed from Cezanne is that there is an inherent abstract order to be gleaned from nature.

When her show opens at the First Street Gallery in New York on November 2nd, Lyons hopes that those who view the show will share her "joy of discovery." Of course, she says gently, "No two people feel the same." It is a sage observation by an artist who doesn't pursue fixed meanings or try to impose them on herself or others. Searching, not finding is her strong point.

Mari Lyons explains her constant curiosity this way: "I'm mainly striving to go deeper into the mysteries and challenges of an art that is always elusive." Elusive they may be, but moments of connection, joy, and spirit flicker brightly through the branches of the painted trees on her painted hillsides.