On November 13, 1980 I purchased a drawing called "Mazurki" by Philip Guston for $4,300.00 from Gallery Paule Anglim in San Francisco. I still have the receipt, but sadly, not the drawing. When I bought it, I was 23 years old, a recent college graduate working as an art salesman in a shopping mall. I didn't have the $4,579.50 -- the total with tax -- needed to pay for the Guston, but I did have a $500.00 deposit, and the very trusting Ms. Anglim let me take the work home, assured that I would make the payments of $500.00 per month.

What on earth was I doing spending forty-five hundred dollars on a work of art? The drawing cost more than double what my car, a used Volkswagen sedan, had cost me the year before. Come to think of it, since gas sold for 85 cents a gallon at the time, the Guston was equal to about 5,000 gallons of gas.

Looking back, there were really several motivations for my grand purchase.

A few years earlier, during my Junior and Senior years as an art student at Stanford University, I had worked as an intern to the collection of Harry and Mary Anderson, better known as "Hunk and Moo." Being surrounded by the Anderson's vast collection, and visiting their home often, I became familiar with the what it felt like to be surrounded by challenging works of modern art. Working for the Andersons had introduced me -- in a big way -- to the pleasures of collecting.

One afternoon in 1979 I was standing in the foyer of the Anderson's home with a group that included some Stanford art students and faculty when I found myself standing in front of "The Coat II" their freshly acquired Philip Guston painting.

Dr. Albert Elsen, a Professor of Art History, and a very intimidating man, mumbled to me that the Andersons had wasted their money. Dr. Elsen was not alone in his feelings: it is important to recognize that few collectors were supporting Guston at this point in his career, and that the Andersons were among the few who believed in what the aging artist was doing. What most collectors wanted were Guston's graceful abstract paintings from the 1950's, not the lumpish, ragged late works that had caused New York critic Hilton Kramer to call Guston "A Mandarin Pretending to be a Stumblebum."

Responding from my gut instinct, I told Elsen that "I loved the painting," and he brusqely asked me "Why?"

The Anderson Collection

Dr. Elsen's blunt question totally stumped me. I babbled something and felt the flush of embarrassment at the total inadequacy of my answer. One reason I may have later been compelled to buy a Guston was so that I could develop a deeper understanding of the man's work and answer Dr. Elsen's question for myself.

The following year I had was totally bowled over by a retrospective exhibition of Guston's work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. His shaggy, maudlin late paintings, many of them still smelling of linseed oil, made a powerful impression on me and deepened my interest. They had something to say, it seemed, that represented hard won wisdom and courage.

The Guston show was very strong stuff. I remember seeing the exhibition with a friend who was in medical school and she literally couldn't handle one painting that featured a pile of legs. I could handle the Gustons -- I saw poetry in the violence -- but I was grossed out a few months later when the same friend took me on a tour of her lab at UCLA where she was slicing brains with a Hobart meat slicer.

Guston died in June of 1980, a month after the opening of the San Francisco show, and that also brought a certain urgency to my feelings about his work. By the time I heard about a show of his drawings being held at the Anglim Gallery in November I was convinced that Guston's art was somehow crucial to me. "I will buy a Guston," I thought to myself grandiosely, "the way that Matisse bought the small Cezanne that became a cornerstone of his artistic life."

When I arrived at the gallery I remember seeing maybe eight or ten spare black and white Guston images. More than half were already sold, and "Mazurki" -- which was still available -- caught my attention. It featured two horizontal rows of blunt, hieroglyphic images that I found interesting and a bit peculiar. It wasn't long at all before it was hung on the wall of my rented room, radiating mystery. Owning "Mazurki" made me feel that somehow I had a foot in the door of the art world, a very imposing social and economic hierarchy that I wanted to be part of.

The Guston drawing certainly gave me something to contemplate, and to puzzle over, but I was never really able to identify all the objects that it contained, or to give the work any kind of fixed meaning. I knew that there was a Polish dance called a "Mazurka" so I assumed that the title meant "a lot of mazurkas" and left it at that. Knowing that Guston had been born in Russia somehow seemed connected to that.

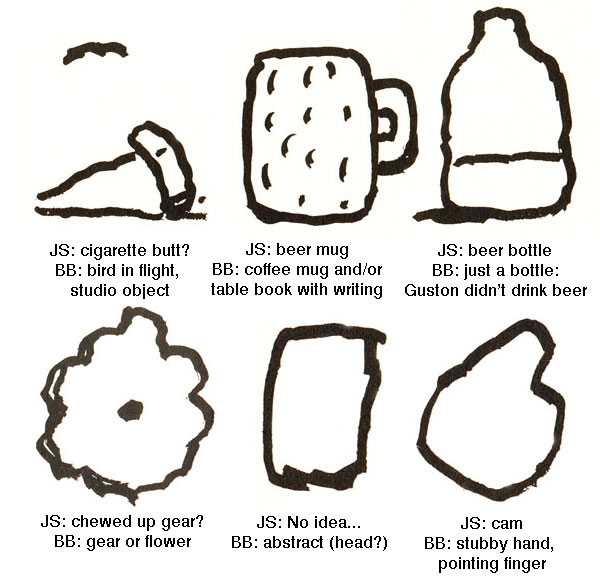

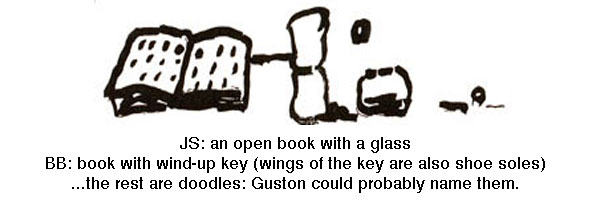

After staring at it for a few months I decided that the work somehow involved associations the artist had about his father who had been a railway machinist. I saw a gear and a cam, a beer mug and beer bottle, and a book filled with vertical dashes. I also thought over the fact that the drawing had been made as an illustration for a book of poetry, "ENIGMA VARIATIONS" by Guston's friend Bill Berkson. Although I never tried to obtain a copy of the original poem I kept it in mind that my drawing was enigmatic along the lines of the poetry that it had accompanied.

By 1981 I had enrolled in UC Berkeley as a graduate student in painting, and the Guston was part of my small collection that included a painting by Robert de Niro Sr. and several drawings by David Park that I had purchased for $200 each. Friends and visitors to my studio rarely commented on it and few would have recognized it as anything of value. One exception was the ceramicist Robert Arneson who visited during an open studio day, and he was mightily impressed.

By 1984 I had finished graduate school and had student loans and credit cards to pay. Foolishly, and a bit desperately, I looked for a buyer for the Guston, and eventually traded it for a work by Patrick Hogan which I then promptly sold for $2,700. A friend of mine says "Never sell real estate" and that is some good advice. I wish someone had told me as a young man "Never sell off your art collection."

It has been more than twenty-five years since I owned "Mazurki" but while going through an old photo album, I recently came across a snapshot of it hanging in the corner over my bed. Thinking it over, I began to realize that even though I no longer own the image, it would be a good project to do some research and answer a question that still nags me: "What was Mazurki about?"

It didn't take much effort to find a copy of Bill Berkson's "ENIGMA VARIATIONS" for sale on the internet, and when it arrived I found that the poem "Mazurki" was the second poem in the book, opposite the image of the drawing that I once owned. Reading the poem -- which Guston had in mind when he created the image -- was something I should have done years ago.

Reading the poem certainly didn't make me say "OK then, I understand everything I need to about the drawing." Just how a poem with a single plural noun, the title, a singular noun, "duffle," and 36 adjectives was connected to the cryptic forms of the drawing was going to be hard to fathom. I was going to need some help.Mazurki

Going

Thirsty

Sidelong

Plus

Duffle

Longer

Modish

Plugged

Ticklish

Simple

Hopeful

Double

Grounded

Slept-in

Sure

Uncertain

Glazed

Familiar

Hung

Deliberate

English

Tonal

Garbed

Terrific

Even

Undiminished

Plural

Anecdotal

Laid

Friendly

Shot

Decided

Torn

Rabid

Crazy

Little

Tops

poem by Bill Berkson

from ENIGMA VARIATIONS

Big Sky, 1975

Fortunately, I was able to contact Bill Berkson via e-mail, and he was more than willing to answer some questions that I really should have asked years ago.

First I asked him about the title, and here is what he had to say:

" 'Mazurki' is two things in my mind: 1) plural of mazurka (Polish dance); and 2) Mike Mazurki, an ex-boxer-type character actor in 1940s movies. The mazurka part is how the poem 'turns' on its one-word lines, all of them adjectives. I'm fond of the poem; I've never written another like it."

Mr. Berkson also took the time to tell me about the objects to be found in the Guston drawing:

"John, some are generic Guston objects, but some objects in the generic-Guston modes of meta-object -- objects that could be one thing and another. 'You're painting a shoe, you start painting the sole and it turns into a loaf of bread; you're painting the bread and it becomes the moon ...' (inexact quote of what PG said to me)."

When Berkson told me how he identified the objects I found that there were some surprises for me, particularly in the fact that he suggested that one object could "morph" into something else. Here is a chart comparing Bill Berkson's identifications of the objects with what I thought I saw many years ago.

So, a poem with thirty-six adjectives had inspired Guston to pen a group of things capable of being more than one thing, some of them cryptic and personal. Both Mazurkis -- the drawing and the poem -- seem designed to multiply ambiguities, just as the title "ENIGMA VARIATIONS" would suggest. Some of the adjectives could seemingly link to some of the images, for example "Thirsty" goes nicely with a bottle, but where could I find am image that works for "Laid" or "Shot?" Add to that, the adjectives found in the poem could describe qualities or states of objects or of people, or of both.

Of all the adjectives in the poem "Uncertain" best describes how I now felt about both the poem and the drawing. Pursuing any kind of fixed meaning for either would not seem to be a good approach. The poem seems to say "these words can spin you in any direction you like." In response, Guston's drawing seems to say "I have a stable of hard-won personal symbols, and the poem has elicited some of them. Make of them what you will." As it turns out, that isn't too far from what Mr. Guston actually did.

A comment in Bill Berkson's e-mail to me led me to contact the Special Collections Department of the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center, at the University of Connecticut. There, among papers donated by Mr. Berkson, archivist Melissa Watterworth located a note from Guston himself, which he had attached to the drawing for Mazurki when he created it. What a find: I now had, in Guston's scrawled handwriting, his own thoughts about Berkson's poem.

I love this poem - the words - I mean the "list" - keeps on working - active - never stops, I mean to say - perhaps that's what I meant by my little object pieces THINGS - as the eyes roam around anywhere in life.

- Philip Guston

Mr. Guston's note had now taken me as close as I will ever get to understanding the drawing. Apparently, the very complex, enigmatic drawing came from the simple acts of looking, seeing and remembering simple objects that were familiar to the artist.

There must be a lesson somewhere in this story. Clearly, when I was younger, my instincts told me to value and look at the work of a mature artist, but I certainly didn't look all that hard at the time. I valued Guston, but not enough that I ever took the time to really understand what I had when I owned it. If I had known just how complicated, subtle and changeable the meanings behind the drawing were I would have hung on to it.

If Dr. Elsen were still alive maybe I would send him an e-mail and finally get back to him about why I like "The Coat." I did see him at a college reunion just before he died, and I doubt he remembered me. If he were around now I might tell him that one of the reasons I now write about art is that his challenge to me caused me to want to better explain in words how I feel about works of art.

Now, in my early fifties, I am amazed at the pull I felt when I came across a snapshot of "Mazurki" in an old photo album. Maturity must make some kind of difference, and now I can at least say that I know something about the collaboration between Bill Berkson and Philip Guston, and what kind of ideas they were working with. They valued looking, poetry, ambiguity, suggestion, collaboration and introspection.

Seeing the world the way I do now, I have to tell you what I think of those qualities.

"Tops"

Written in 2006, published in the Huffington Post January, 2011