Author's Note: On February 21st the DesMoines Register announced that a bill proposing to force the sale of Jackson Pollock's "Mural," in the collection of the University of Iowa's Art Museum, had died.

This blog, about the controversy generated by the bill, and also about the cultural forces surrounding it, was composed while the bill was still under consideration. It is hopefully still worth reading, as, in the words of a good friend "This idea will come up again, and similar proposals to sell works of art from museum and university collections will multiply as the economy continues to struggle."

In "Jackson Pollock: An American Saga," a sprawling 796 biography of the artist by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, there is a description of a very awkward Pollock family reunion that took place at Pollock's Long Island farmhouse in July, 1950. During the family gathering, Pollock, an insecure man who had struggled with poverty and alcoholism for most of his life, bragged about his growing fame to his visiting brothers.

"I'm the only painter worth looking at in America. There really isn't anybody else," Pollock crowed. He then pointed to one of his abstract drip paintings, "Lavender Mist," and challenged his brother Frank: "Buy that painting for $15,000 and one day it will be worth $100,000."

Pollock, who was being grandiose in predicting such a hefty price for one of his paintings in the future, was low in his estimate. In 2006 his "No. 5, 1948" was sold to an unknown collector for $140 million dollars, a price 1,400 times higher than the seemingly outrageous prediction the artist had once made in front of his family.

Pollock's position as the preeminent American painter of the 20th century is now firmly rooted -- he had no need to be insecure about his reputation -- and prices for Pollock's key works have soared into the stratosphere. Prices for major Pollocks are so high, as are the prices for other blue chip works of art, that they seem divorced from the realities a struggling world economy.

Great works of art, which ideally should serve as symbols of human experience refined into culture, are gaining attention as symbols of the almost feudal inequalities that plague the world's distribution of wealth. We like to think of masterworks as "priceless" but as the world's economy teeters, more and more people are realizing that they have price tags.

Among those paying rapt attention are Asian and Middle Eastern billionaires who are developing a hankering for American masterworks. Authoritarian capitalists have embraced Rothko, Warhol and Pollock, and they have mountains of dollars ready to spend on art.

I have recently been reading and thinking about a bill proposed in the Iowa House of Representatives by Rep. Scott Raeker (R). The bill would force the University of Iowa to sell Jackson Pollock's "Mural," valued at an estimated $140 million dollars, and possibly worth more. The proceeds of the sale would reportedly create an endowment fund that would reportedly give between 750 and 1,000 students full scholarships to U of Iowa in perpetuity.

This is the second time that such a sale has been proposed, and the idea was shot down the first time around. Now, with another battle brewing, The Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) and the American Association of Museums (AAM) have issued a powerful joint statement explaining their alarm over the idea. Sally Mason, the President of the University of Iowa, has also made her opposition clear:

"This is an issue that I, and the entire University of Iowa community, care deeply about and my position has not changed. I do not want to sell the painting."

The proposed sale is dividing Iowans and other interested parties down political fault lines, and turning politicians into art critics. Last Fall the Iowa Press-Citizen quoted Republican Senator David Johnston, who supports the bill, as calling the Pollock mural "a fraud." Isn't it interesting that a senator is so anxious to get an astronomical price for something he considers fraudulent?

Representative Raeker, the Republican who authored the bill to force the Pollock sale, doesn't have anything so caustic to say about the painting. When I emailed him about his views on Pollock he responded with a politician's flair, stating: "I believe the 'Mural' is a fine piece of art and has considerable value on many levels."

The proposed sale is supported by at least one University of Iowa Regent, journalist and businessman Michael Gartner, who has said that "providing scholarships to Iowa students is far more important than owning a painting."

On a Facebook page started in 2008 by Tom Nixon there are 552 members listed, but not all of them are there to be supportive. One comment on the site, left by Justin Whitlock of Cedar Rapids reads: "So, the University wants to sell something they own to help pay for flood damage INSTEAD of sucking the money from flood relief funds like FEMA or the state or tax payers... SELL IT!" Another comment, sarcastically notes that U of Iowa "leads the nation in binge drinking" making it a fine setting for a Pollock.

Tom Nixon, a U of Iowa grad notes that "... the Pollock and the rest of the University's collection could accurately be called one of the best kept secrets in Iowa," hopes the controversy over the Pollock will make Iowans more aware of the importance of what they have. Acknowledging that "money is tight" he still feels strongly that "A garage sale of our prized cultural possessions is no solution at all."

Iowa's Democratic senators are pledging to block the sale. There are indications that the sale could face legal challenges, and also that the University of Iowa Museum could lose its accreditation. Speaking for myself, I don't think the sale of the mural is a good idea -- deaccessioning works of art from museum collections rarely is -- but the moral issues raised by the proposed sale are thought provoking.

It is deeply troubling that so many people are struggling while art prices soar. The situation strikes me as being Medieval. Of course, a textbook capitalist would say "It's simply supply and demand, and the market is doing its job," but I have grown disenchanted with that perspective.

Who, I have been wondering, might provide some explanations and insights to put this situation into a different light? Who might be able to offer a more profound view or even some solutions? I wanted a perspective that would be outside the usual polarities of Democrat/Republican or Liberal/Conservative.

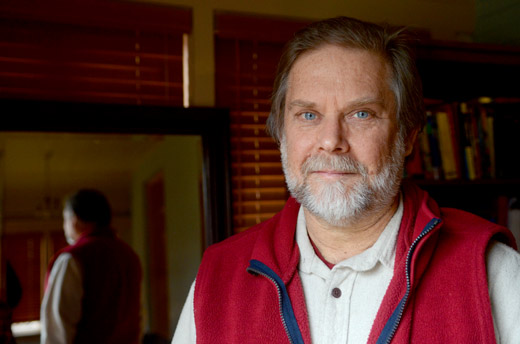

The best person I could think of was David R. Loy, an American author and professor who is an authorized teacher in the Sanbo Kyodan lineage of Japanese Zen Buddhism. Loy, whose writings present a dialogue between modernity and Buddhism, has stated that modern Capitalism is a religion. In Loy's view, modern capitalistic culture is a troubled belief system that is dogged by insecurity.

This excerpt from Loy's essay "Why We Love War" provides a sample of his point of view:

"The modern world can keep many of us alive longer and sometimes makes death less physically painful, but it has no answer to the groundlessness that plagues us individually and collectively, for nothing in the world can fill up the bottomless hole at our core. Without understanding what motivates us, we end up clinging; not only to physical objects but also to symbols..."

Clinging to physical objects and symbols? That sounds like art collecting to me. I was able to contact Loy via e-mail, and I filled him in on the Pollock situation. Then I asked him a few questions, including this one:

"In a world filled with suffering, what can be said about so much money going towards art purchases?" Loy promised to reflect on my questions and two days later I reached him on his cellphone while he was out for an afternoon walk in Ohio. We never directly dealt with the question "Should the Pollock be sold or not?" but instead talked about Loy's views of the cultural and political forces surrounding that question.

We started by talking a bit about the way that art is given a dollar value. "The basic point," Loy told me, "is that in this culture everything becomes fundamentally a commodity." Art, like any other commodity "has meaning and value if transformed into those terms."

Loy went on to suggest that one thing collectors do when they trade dollars for a Pollock might be to "appropriate the West." Certainly anyone who would want to purchase Pollock's mural would be symbolically buying a piece of America. Of course, maybe the problem is that the people of Iowa don't see it that way, while art lovers on the two coasts do.

In "Pollock: An American Saga" Pollock is quoted as saying that the inspiration for his abstract mural came from a vision of the American plains. "Cows and horses and antelopes and buffaloes. Everything is charging across that goddamn surface," he said. Part of what makes Pollock so great as an artist is that he was part Marlboro Man, part Monet. He channeled masculine American individuality into something abstract and subjective; a difficult feat.

Above: A Detail of Pollock's Mural, photo by Theron LaBounty

As our conversation continued Loy was making his way up a hill, and the pace of our conversation seemed to pick up in rhythm with his exertion. If anything, the Buddhist scholar was beginning to sound like an economist.

There is, he reminded me "a huge pool of money sloshing around." It is a world of global financial speculation full of "games" where "a great deal of money can be made in a few seconds." The result, when you get a "tidal wave of money" is that bubbles form wherever money " decides to go." Loy has that right: art is indeed the place that a tsunami of money seems to go these days.

I asked Loy, who has stated that the modern west is caught in a "crisis of immortality," if works of art served as "relics" for collectors now, in a way that the bones of a saint did a thousand years ago. He said "yes" and told me that "money has become an immortality symbol." Art dealers, he suggested, must know how to summon up fears about mortality and our insecurity.

It should be noted that when Loy talks about "insecurity" in his writings, he often connects it to a concept that he calls "lack" something he sees permeating the modern capitalist world. "Lack" he says, "is my interpretation of the dukkha (suffering) that occurs due to our discomfort with and resistance to our shunyata (emptiness)."

In his book "The $12 million Dollar Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art," economist Donald N. Thompson quotes Howard Rutkowski, the director of Bonham's auction house who says: "Never underestimate how insecure buyers are about contemporary art, and how much they need reassurance." Collectors apparently are desperate for the validation of their taste by "experts."

While doing research on Pollock's "Mural" I learned that the two artists who had the job of installing it in dealer Peggy Guggenheim's apartment -- David Hare and Marcel Duchamp -- cut 8 inches off the canvas to make it fit. Pollock was told about the trimming, but he was drunk and "didn't care." As I read this I thought to myself "Pollock is so important now that if someone suggested cutting 8 inches off the other edge of the mural there would be a national debate." Of course, the trimming might sell for millions that could provide scholarships.

As my call with David Loy progressed, and he neared the top of a hill, he gave me a few more things to think about. "From the contemporary Buddhist point of view, our lack is externalized." This manifests itself in "all the things that money can buy, and in our preoccupation with fame."

"We can only truly feel real," Loy continued, "through the eyes of others."

At this point in the conversation I felt that I had more than enough information to work with, and I thanked David for his time. Later, looking over my notes, something he had said really jumped out at me:

"The real problem isn't the future, the real problem is right now."

Talking to David Loy was energizing, and as I reflected on our conversation over the next few days, I realized that true to his form as a Zen teacher, he had caused me to ultimately come up with more questions than answers. He had given me many interesting insights, but I continued to struggle with the moral issues raised by the absurd dollar values given to works of art.

The idea of selling Jackson Pollock's "Mural" seems so wrong, but the idea of helping people right now seems so right. In fact, this is what the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, established by Pollock's widow Lee Krasner in 1985, was founded to do. With a mission of providing financial assistance to artists, the Foundation has turned the proceeds from the sale of Pollock paintings into a financial safety net for thousands of grantees. In its relatively short lifespan the PK Foundation has given out some 3,500 grants totaling over $53 million dollars.

If Pollock paintings have sold for insane amounts of money, it cuts both ways. Through the generosity of the Pollock-Foundation, cash derived from the sale of Pollocks has helped many worthy people cope with the problems of "right now." The same high prices have also caused all of us to understand, in our "money is how we value things way" that Pollock's paintings are important symbols of American culture.

Loy sent me one more e-mail when he got home after his walk.

John, he asked "Was it Warhol who said: 'Art is whatever you can get away with'?" David's email, I realized posed a kind of final Zen question intended to help me clarify my thinking.

My response was to have an "Aha!" moment and laugh to myself. Artists aren't the ones who try to get away with things. Politicians do that too.

For a moment of attention and glory, a small group of Iowa politicians wants to see if they can pull a fast one and put a price on something priceless. They are a bit jealous that Jackson Pollock has achieved immortality and they don't quite understand how he did it. Maybe, they are thinking, they can latch on and convert a potent symbol of American culture into cash and political capital.

Why, I have to wonder, aren't they suggesting that we sell the Lincoln Memorial too? It is, after all, another concrete symbol of an American who mastered his anxiety -- his sense of "lack" -- and attained greatness. There must be a Chinese billionaire who would pay to move it, and the cash would be a big help in paying down the federal deficit.

By the way, that was a Zen question.