A friend recently asked me what I think of Andy Warhol. Without hesitating, I replied that I don't care for Andy Warhol's art. Noting my friend's surprise I added that I do think Warhol was a genius, but not as an artist. I think of him as a genius in the field of sociology.

Later, as I searched the internet to find out if there were others who shared my view, I found no evidence of anyone else referring to Warhol as a sociologist. I did, however, find many references to the fact that he is a divisive figure:

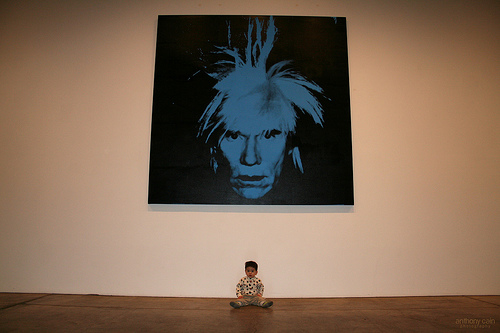

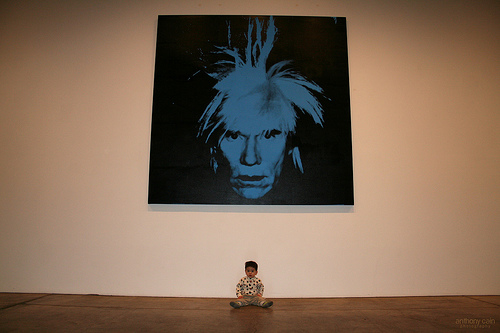

Andy Warhol "Self-Portrait," at the Warhol Museum: Photo © Anthony Cain

If I had to choose between those two views "corrupter of art" works best for me. I find many of Warhol's works chilling, and feel that his legacy has been largely negative. If, as David Dalton implies, there are many others out there who share that view, we haven't done much to dampen the art market's enthusiasm for Warhol's works.

As far as the art market is concerned, Warhol's reputation is solid gold. In fact, the dollar values of Andy Warhol's signature works have done exactly what gold has done: they have risen in reaction world fiscal instability.

When things are uncertain, the market seems to say, Warhol will outperform other investments. In a blog on the anniversary of the artist's death -- "The Top Ten Andy Warhol Prices" -- blogger Marion Maneker notes that seven of the top ten Warhol prices were achieved after the financial crash of 2008. The Warhol record of $100 million, achieved in a private sale for a photo-silkscreen image of Elvis Presley, repeated 8 times, occurred in October 2008, the same month that the world's financial crisis took off.

I don't see artistic merit supporting the gilded price range for Warhol's works. Personally, when Warhol stopped painting and began using photo-silkscreens as the basis of his imagery he lost me. There is something in the connection between the brain, the hand, the brush, and the canvas that I find essential to painting. So, Warhol in my mind made paintings without painting. Call me a reactionary, but Warhol cheated.

In my view Warhol's prices are tied to the fact that works of art have become financial instruments whose value is pegged to an artist's fame. Buying a Warhol celebrity portrait is analogous to buying a very, very expensive baseball card. A 1914 Baltimore News Babe Ruth rookie card is just a piece of cardboard with a printed image, but a good one might bring half a million dollars. A 1914 Chicago Federals Joe Tinker card, also a piece of cardboard, can be yours for about $200.00. Has anyone ever heard of Joe Tinker?

Fame gives items what I call a "relic value" and buying them makes collectors feel close to the fame of those they are associated with. The idea of relic value derives from the fact that Medieval collectors would pay quite a tidy sum for relics, i.e. an alleged finger-bone from Saint John the Baptist, a famous and much revered saint.

No other artist of the 20th century understood fame quite the way Warhol did: like a dead saint, he seems to have a firm grip on it even from the grave. Warhol depicted famous people, cultivated friendships with famous people, became famous, and in the context of our current society, achieved immortality. Quite a trick, don't you think?

Warhol's genius lay in his understanding of religion and sociology. In particular, the ideas that he intuited -- or borrowed -- about the changing role of art in a media society were devastatingly right. His grasp of the sociological changes going on around him informed his decisions to choose image over content and to speed up his production of works through mechanical methods.

He assumed -- correctly -- that more and more people were coming to share his abbreviated idea of what made a good painting, commenting: "My idea of a good picture is one that's in focus and of a famous person."

Warhol deserves credit for his insights, but so does the sociologist and media theorist Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980) who Warhol once referred to as an "Honorary Muse." Studying the two men's ideas side by side is a fascinating exercise.

Andy Warhol and Marshall McLuhan: Photomontage by Photofunia.com

Warhol and McLuhan barely knew each other, but they certainly did know of each other.

McLuhan's groundbreaking book "The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man" was published in 1951, a year before Warhol had his first New York exhibition. It is hard to believe that Warhol, who had been working in advertising, hadn't at least heard of the book, which described in depth how film posters, comic books, advertisements and magazine covers exerted their persuasive powers.

McLuhan was known for his aphorisms, and many of them are dead-ringers in terms of mirroring Warhol's social and aesthetic observations. Warhol's famous quip that everyone would have "15 minutes of fame" in the future is believed to have been paraphrased from McLuhan. Another famous quote "Art is what you can get away with," has been attributed to both men, and there seems to be no agreement about who said it or who said it first.

It is interesting to note that in the mid-60s after Warhol and McLuhan did briefly meet, McLuhan later commented that Warhol was a "rube." Do I sense some competitiveness there?

Art historian Gregory Battcock, gives Warhol the edge:

So, Battcock views Warhol as predicting the end of painting. What, one has to wonder was "killing" it? Mass media -- movies television and magazines -- all played a role, but art's real usurper, at least in Marshall McLuhan's view, was advertising.

"Advertising" declared McLuhan, "is the greatest art form of the 20th century." Warhol, of course, began his career as a commercial illustrator, and some of his earliest Pop works are deadpan copies of advertisements. Advertising in the 20th century did what religious art had done in the 13th century: it used its imagery and authority to create images that helped focus mass desires and beliefs. Of course, if you believe as I do that capitalism is a religion, the parallels are clear.

McLuhan who converted to Roman Catholicism, and Warhol, who was raised Catholic, were both very aware that the mass culture of the late 20th century was supplanting religion. In McLuhan's view, electronic mass media worked against the private and the metaphysical:

He had that right.

Warhol's portraits, which critic Robert Hughes says stripped the idea of portraiture down to its "bare chassis" lacked any shred of the metaphysical. Complexity, in the form on allegory, iconography, or philosophical speculation, wasn't necessary in a media society. Just the bare specter of celebrity, processed mechancially, was all that many of Warhol's key images relied on. A passive aggressive artist if ever there was one, Warhol understood the chilling unquestioned authority of fame as well as any dictator.

Andy Warhol and Vladamir Putin: Photomontage by Photofunia.com

Marshall McLuhan says that "One of the effects of living with electric information is that we live habitually in a state of information overload." What Warhol, in turn, understood about fame is that it cuts down the number of people we have to be interested in to a manageable number. Celebrities are the town characters in our "Global Village" -- to use McLuhan's phrase -- and they replace the saints of earlier centuries.

Andy Warhol once said that Pop art was about "liking things." I have always found that quote ingenuous: in my view Warhol's choices of subject matter tended towards parody. Yes, he was fascinated by Marilyn Monroe's power as a celebrity/goddess, but the silkscreen images he created after her death make Monroe appear clownlike. This wouldn't surprise Marshall McLuhan who believed that "Antipathy, dissimilarity of views, hate, contempt, can accompany true love."

Warhol Marilyn by caksy, on Flickr

One of Warhol's most enduring revelations was that in a media society, connoisseurship is doomed. In a society with an all powerful, highly persuasive media, careful informed distinctions weren't necessary when choosing what to buy. All that people needed, however much money they had, were the right brands.

"What's great about this country," Warhol once said, " is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest." In today's global society plutocrats seem to be replacing aristocrats, and Warhol seems dead on that the world's taste has flattened. What does it take to become an art collector? Lots and lots of money, and if you need taste there are still advisers who will rent you theirs for a fee.

Of course, in the Warholian view, even the art advisers will be gone in a few decades: "Some day everybody will just think what they want to think, and everybody will probably be thinking alike; that seems to be what is happening."

The more I read Warhol's thoughts and predictions, the more strongly I feel that his legacy has been damaging. Using his strategies -- let others make your art, become a social figure, and do everything you can to manipulate your audience -- a host of other artists have transformed whatever fame they have managed into dollars.

Although you don't often see all these names on the same list, I think of Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Mark Kostabi and Thomas Kinkade as second-generation Warholians. In the third generation you get Mr. Brainwash.

On the other hand, the more I read about Marshall McLuhan, the more impressed I am by his wisdom. He comes across as a complex and highly original thinker, as compared to Warhol who was a highly effective borrower of ideas. In fact, one of my favorite McLuhan quotes seems to be a warning for the future, where, as predicted by Warhol, where everyone will "think alike:"

Insight? Understanding? Those are essential qualities for a portrait painter, and perhaps McLuhan would have made a fine one. He and Andy Warhol should have switched jobs.

Marshall McLuhan: Photomontage by Photofunia.com

Later, as I searched the internet to find out if there were others who shared my view, I found no evidence of anyone else referring to Warhol as a sociologist. I did, however, find many references to the fact that he is a divisive figure:

"Depending on your point of view, Andy Warhol is the greatest American artist of the second half of the 20th century or a corrupter of art who destroyed painting and took us down the slippery slope of postmodernism."

- David Dalton

If I had to choose between those two views "corrupter of art" works best for me. I find many of Warhol's works chilling, and feel that his legacy has been largely negative. If, as David Dalton implies, there are many others out there who share that view, we haven't done much to dampen the art market's enthusiasm for Warhol's works.

As far as the art market is concerned, Warhol's reputation is solid gold. In fact, the dollar values of Andy Warhol's signature works have done exactly what gold has done: they have risen in reaction world fiscal instability.

When things are uncertain, the market seems to say, Warhol will outperform other investments. In a blog on the anniversary of the artist's death -- "The Top Ten Andy Warhol Prices" -- blogger Marion Maneker notes that seven of the top ten Warhol prices were achieved after the financial crash of 2008. The Warhol record of $100 million, achieved in a private sale for a photo-silkscreen image of Elvis Presley, repeated 8 times, occurred in October 2008, the same month that the world's financial crisis took off.

I don't see artistic merit supporting the gilded price range for Warhol's works. Personally, when Warhol stopped painting and began using photo-silkscreens as the basis of his imagery he lost me. There is something in the connection between the brain, the hand, the brush, and the canvas that I find essential to painting. So, Warhol in my mind made paintings without painting. Call me a reactionary, but Warhol cheated.

In my view Warhol's prices are tied to the fact that works of art have become financial instruments whose value is pegged to an artist's fame. Buying a Warhol celebrity portrait is analogous to buying a very, very expensive baseball card. A 1914 Baltimore News Babe Ruth rookie card is just a piece of cardboard with a printed image, but a good one might bring half a million dollars. A 1914 Chicago Federals Joe Tinker card, also a piece of cardboard, can be yours for about $200.00. Has anyone ever heard of Joe Tinker?

Fame gives items what I call a "relic value" and buying them makes collectors feel close to the fame of those they are associated with. The idea of relic value derives from the fact that Medieval collectors would pay quite a tidy sum for relics, i.e. an alleged finger-bone from Saint John the Baptist, a famous and much revered saint.

No other artist of the 20th century understood fame quite the way Warhol did: like a dead saint, he seems to have a firm grip on it even from the grave. Warhol depicted famous people, cultivated friendships with famous people, became famous, and in the context of our current society, achieved immortality. Quite a trick, don't you think?

Warhol's genius lay in his understanding of religion and sociology. In particular, the ideas that he intuited -- or borrowed -- about the changing role of art in a media society were devastatingly right. His grasp of the sociological changes going on around him informed his decisions to choose image over content and to speed up his production of works through mechanical methods.

He assumed -- correctly -- that more and more people were coming to share his abbreviated idea of what made a good painting, commenting: "My idea of a good picture is one that's in focus and of a famous person."

Warhol deserves credit for his insights, but so does the sociologist and media theorist Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980) who Warhol once referred to as an "Honorary Muse." Studying the two men's ideas side by side is a fascinating exercise.

Warhol and McLuhan barely knew each other, but they certainly did know of each other.

McLuhan's groundbreaking book "The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man" was published in 1951, a year before Warhol had his first New York exhibition. It is hard to believe that Warhol, who had been working in advertising, hadn't at least heard of the book, which described in depth how film posters, comic books, advertisements and magazine covers exerted their persuasive powers.

McLuhan was known for his aphorisms, and many of them are dead-ringers in terms of mirroring Warhol's social and aesthetic observations. Warhol's famous quip that everyone would have "15 minutes of fame" in the future is believed to have been paraphrased from McLuhan. Another famous quote "Art is what you can get away with," has been attributed to both men, and there seems to be no agreement about who said it or who said it first.

It is interesting to note that in the mid-60s after Warhol and McLuhan did briefly meet, McLuhan later commented that Warhol was a "rube." Do I sense some competitiveness there?

Art historian Gregory Battcock, gives Warhol the edge:

"Warhol was, during the sixties, a visual Marshall McLuhan. Though more profound than McLuhan and more a person of his time, Warhol correctly foresaw the end of painting and became its executioner."

So, Battcock views Warhol as predicting the end of painting. What, one has to wonder was "killing" it? Mass media -- movies television and magazines -- all played a role, but art's real usurper, at least in Marshall McLuhan's view, was advertising.

"Advertising" declared McLuhan, "is the greatest art form of the 20th century." Warhol, of course, began his career as a commercial illustrator, and some of his earliest Pop works are deadpan copies of advertisements. Advertising in the 20th century did what religious art had done in the 13th century: it used its imagery and authority to create images that helped focus mass desires and beliefs. Of course, if you believe as I do that capitalism is a religion, the parallels are clear.

McLuhan who converted to Roman Catholicism, and Warhol, who was raised Catholic, were both very aware that the mass culture of the late 20th century was supplanting religion. In McLuhan's view, electronic mass media worked against the private and the metaphysical:

"Christianity definitely supports the idea of a private, independent metaphysical substance of the self. Where technologies supply no cultural basis for this individual, then Christianity is in for trouble."

He had that right.

Warhol's portraits, which critic Robert Hughes says stripped the idea of portraiture down to its "bare chassis" lacked any shred of the metaphysical. Complexity, in the form on allegory, iconography, or philosophical speculation, wasn't necessary in a media society. Just the bare specter of celebrity, processed mechancially, was all that many of Warhol's key images relied on. A passive aggressive artist if ever there was one, Warhol understood the chilling unquestioned authority of fame as well as any dictator.

Marshall McLuhan says that "One of the effects of living with electric information is that we live habitually in a state of information overload." What Warhol, in turn, understood about fame is that it cuts down the number of people we have to be interested in to a manageable number. Celebrities are the town characters in our "Global Village" -- to use McLuhan's phrase -- and they replace the saints of earlier centuries.

Andy Warhol once said that Pop art was about "liking things." I have always found that quote ingenuous: in my view Warhol's choices of subject matter tended towards parody. Yes, he was fascinated by Marilyn Monroe's power as a celebrity/goddess, but the silkscreen images he created after her death make Monroe appear clownlike. This wouldn't surprise Marshall McLuhan who believed that "Antipathy, dissimilarity of views, hate, contempt, can accompany true love."

One of Warhol's most enduring revelations was that in a media society, connoisseurship is doomed. In a society with an all powerful, highly persuasive media, careful informed distinctions weren't necessary when choosing what to buy. All that people needed, however much money they had, were the right brands.

"What's great about this country," Warhol once said, " is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest." In today's global society plutocrats seem to be replacing aristocrats, and Warhol seems dead on that the world's taste has flattened. What does it take to become an art collector? Lots and lots of money, and if you need taste there are still advisers who will rent you theirs for a fee.

Of course, in the Warholian view, even the art advisers will be gone in a few decades: "Some day everybody will just think what they want to think, and everybody will probably be thinking alike; that seems to be what is happening."

The more I read Warhol's thoughts and predictions, the more strongly I feel that his legacy has been damaging. Using his strategies -- let others make your art, become a social figure, and do everything you can to manipulate your audience -- a host of other artists have transformed whatever fame they have managed into dollars.

Although you don't often see all these names on the same list, I think of Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Mark Kostabi and Thomas Kinkade as second-generation Warholians. In the third generation you get Mr. Brainwash.

On the other hand, the more I read about Marshall McLuhan, the more impressed I am by his wisdom. He comes across as a complex and highly original thinker, as compared to Warhol who was a highly effective borrower of ideas. In fact, one of my favorite McLuhan quotes seems to be a warning for the future, where, as predicted by Warhol, where everyone will "think alike:"

"A point of view can be a dangerous luxury when substituted for insight and understanding."

Insight? Understanding? Those are essential qualities for a portrait painter, and perhaps McLuhan would have made a fine one. He and Andy Warhol should have switched jobs.