My interest in theatrically is like watching people in an airport -- something you don't even really look at. - William Leavitt

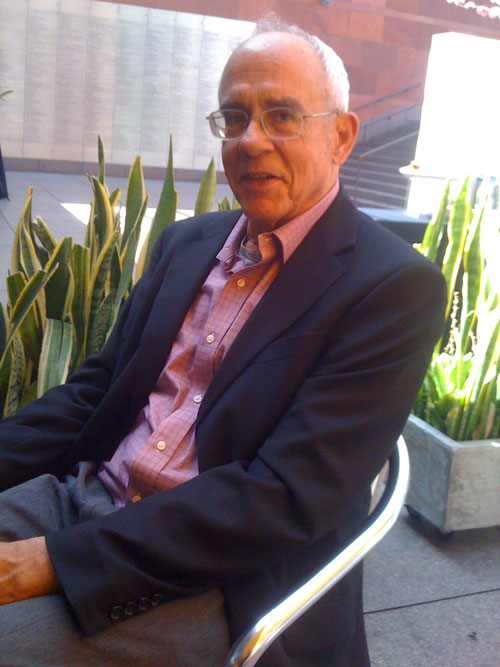

Seated on a sleek metal chair at the MOCA Cafe, artist William Leavitt looked relieved. Chatting with a few friends after the Media Preview for "William Leavitt: Theater Objects," on view at MOCA Grand Avenue through July 3rd, Leavitt was again where he likes to be: on the sidelines, watching.

During an earlier press conference, Leavitt was seated at the far left of a table facing a crowd of more than 50, where he listened to tributes from MOCA curators Paul Schimmel and Bennett Simpson, and also from former MOCA curator Ann Goldstein, now the director of Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum. Praised by Simpson as a "keen observer of the mass production and mannerism of tastes" Leavitt, who looks a bit like comedian Buck Henry, hovered close to the table and nervously took it all in.

Leavitt, who will turn 70 in November, has spent more than 45 years scanning the edges and interior spaces of Los Angeles, a city that he filters through a postmodern sensibility. When it came time for Leavitt to speak, he was quietly gracious, commenting that he was very pleased to be a part of the history and traditions of MOCA. He also recalled first arriving in Los Angeles and finding it "peculiar" but added, as a kind of public confession, that over the years he has become a bit more peculiar himself.

Peculiarity -- and particularity -- are in fact Leavitt's strengths, and the effect of his MOCA retrospective is to present a view of the culture of Los Angeles that is cerebral, slightly odd and sometimes funny. His photographs, paintings, and mixed media installations demonstrate that Leavitt, a self-conscious man, has turned his anxieties inside-out and calmed them with intelligence and a pack of cigarettes. Writer Carol Ann Klonarides says that Leavitt deals with "conventional things in a dramatic way," an astute observation.

Visitors to Leavitt's show need to keep in mind that Leavitt is, along with being a visual artist, a musician and dramatist. For example, in 2002 he presented a work called "The Radio" which featured three actors delivering non-linear dialogue in parallel with a score he composed to represent a fourth character.

Set against the clean, antiseptic spaces of MOCA's Grand Avenue galleries, Leavitt's seminal works seem alien at first glance. Then, with a bit more consideration, the realization comes that Leavitt has nailed the strangeness of a time and place not for from Isozaki's pristine galleries . One of his masterpieces, "California Patio," a 1972 mixed media installation, nails the era in Southern California where every ranch style house 50 miles of the coastline had a sliding glass door that opened out to tropical plants and Malibu lights.

When "Patio" was first shown it featured plastic plants, as did some of Leavitt's other installations. Asked if this was meant to be a comment on our "plastic society" Leavitt responded: "It's just that the plastic plants are much easier to use." Now in the collection of the Stedelijk, the first purchase made by Director Ann Goldstein, "California Patio" is a real piece of cultural anthropology that must be pleasantly puzzling to the citizens of Amsterdam.

Leavitt has an interest in interiors and their narrative potential. His 1984 pastel "Interior with Cactus Painting and Spiral" is weirdly spare. The image of looming Joshua trees that decorates on wall is drawn in an off-hand, notational style, and the various textures -- wallboard, paneling and wood-grain -- are utterly banal. If there is something off here, as Leavitt seems to suggest, he isn't going to be the one to tell you what it is.

Leavitt is inclined towards thinking schematically. He also likes visual loose ends, thematic disconnections and and other puzzles. In some of his drawings and photo groupings he raises questions Baldessari style by pairing seemingly unrelated images. Leavitt calls this process "random selection."

One pastel, "Enterprise Tomatoes," includes tomato plants growing in metal cages alongside an image of the Starship Enterprise. The end result is offhandedly surrealistic, especially since the images are drawn as if they were meant for a coffee house chalkboard.

Artificiality is a key element in Leavitt's paintings, and also in his installations. He likes electric lighting and uses it to hint that everything about his work is staged. When nature is present in Leavitt's images, it is perfunctory, contained and even a bit stunted. All of LA, Leavitt seems to imply, is a giant studio backlot, and nature is a set of props.

After I spent several minutes looking into the colored windows of the nearly identical stucco hillside homes in Leavitt's "Hillside Lights (incandescent)" I realized that each window seemed to frame its particular source of artificial light, right down to the detail of a big screen TV giving off a ghostly pale blue-gray. One of Leavitt's projects seems to be to distill human presence down to traces and empty settings.

William Leavitt, Detail of "Hillside Lights (Incandescent)," 2004, oil on canvas 24 x 60 inches

Courtesy: Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles

The lonely vibe of Leavitt's work may be the reason that curator Paul Schimmel compared him to painter Edward Hopper during the MOCA media event. There is a strong sense of people passing through Leavitt's world, and in some sense the places depicted in his works stand in for the absent characters they seem to imply.

Spending time in "Theater Objects" is mildly unsettling. At one moment you find yourself taking in something utterly familiar, and a moment later another element of the show may strike you as compellingly strange. Looking at a phony torch in one installation -- it featured fluttering colored acetate flames -- I found myself remembering the plug in campfire that I sat around during Woodcraft Ranger meetings in the 1960s.

Yes, I grew up in Los Angeles, and I was having a "William Leavitt" moment.

If you too grew up in the suburbs of LA, you are going to have some "William Leavitt" moments yourself. I walked out of the exhibition realizing that Southern California is a little more peculiar than I thought it was.

"Just what is this city?" the show seems to ask. A city with an airport restaurant that belongs in a comic book? An existential nowheresville tinged by noir? A sheetrock dystopia decorated with paintings of jungle cats and manta rays?

If anything, it is Leavitt's sense of the familiar that raises the most questions. Ann Goldstein, in conversation with the artist in a panel discussion, put it this way: "It's the recapturing of the ordinary in a world where we expect everything to be extraordinary."

William Leavitt has spent more than 40 years asking the questions and setting the stage, creating "Theater Objects" for a very ambiguous play. While seeing the show, you will be part of the play. After you leave, you will find that you still are. "You're looking for what happens next," is how Leavitt puts it.

3px;">Nine Artists (Updated) by John Seed | Make Your Own Book