Edith Park Truesdell (1888-1986) was a painter, a teacher, a writer and a poet. She was also the aunt of a very famous artist: the Bay Area Figurative painter David Park (1911-1960). Truesdell, who exhibited her paintings over a span of more than 75 years, outlived her nephew by 26 years and was able to enjoy the unfolding of Park's posthumous success, a development that delighted her greatly.

On the other hand, when exhibiting her own paintings late in life, Truesdell had to put up with people commenting that Park had influenced her as an artist. "She loathed that," recalls Natalie Park Schutz, Truesdell's great-niece, and Park's eldest daughter; "It was very much the other way around."

Edith Truesdell was a highly trained and accomplished artist whose art and presence affected the course of her nephew's development profoundly. Truesdell and Park were kindred spirits, and the shared qualities of their art -- an affinity towards elegant simplicity in representation, and a feeling for nuance -- emanated from deep familial and artistic connections.

In her book David Park, Painter: Nothing Held Back, Helen Park Bigelow is clear about the bond between her father David and his aunt Edith, asserting that "She (Edith) was David's mentor and ally all his life." Both Edith and David, who his aunt had recognized early on as being "A slow blossomer, almost a black sheep," had quietly rebelled against their minister fathers and found their calling in art. "As with David," Bigelow writes, "painting was always Edith's fierce, abiding engagement."

Edith Park was born in 1888, in Derby, Connecticut, the youngest child in a family of one boy and five girls. Their parents were Charles Ware Park and Anna Maria Ballentine Park. Charles, who an 1883 New York Times clipping describes as coming from "famous stock" was the son of a "well-known divine" and a graduate of Amherst and Andover. He served the Congregational Church as a missionary to India for ten years before ill health had caused him to return to the U.S. in 1881. After being rejected for a position with a New Haven Congregational church -- the elders were concerned by the fact Park didn't believe in infant baptism -- Charles Park preached as a Unitarian and was dropped by the Congregational Church. Like Charles, Edith's mother Anna came from a highly principled religious background; her father had also served as a missionary in India where she had been born.

Charles died at the age of 50 in Pittsfield, Massachusetts - he had been there only 3 months and hadn't yet preached a single sermon - leaving Anna a widow. Anna then moved the family to Wellesley, where her daughter Nell was an undergraduate at Wellesley College. By renting out rooms to carefully chosen young ladies from Wellesley the widow Park managed to make ends meet for the family. Despite her father's passing Edith later had pleasant memories of the period, and was very close to her siblings. An artistic girl who also played the cello, when she turned 18 in 1906 Edith did not follow her older sisters in attending Wellesley College; "She was different," says Natalie Park Schutz. Instead, Edith became a student at the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Truesdell's instructors at the museum school were associated with the "Boston School," a group of American Impressionists noted for the elegance and refinement of their subject matter. Artist and critic Guy Pène Du Bois commented in 1915 that the painters of the Boston School were "...more interested in the rendering of beauty than of fact." Truesdell's teachers included Frank Weston Benson, known for luminous paintings of his wife and daughters, Edmund C. Tarbell, a popular instructor who grounded his students in academic technique, and Philip L. Hale, the author of an important early book about the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675),

In 1912 Edith, who had contracted tuberculosis, left to recover in Denver. She remained there through 1913, and returned to the Boston Museum School in 1915. In 1916 Edith won a gold medal -- the first of many that would come her way -- for a painting she submitted to the school's summer exhibition.

In her mid 20s, the age by which proper young women of the period were expected to have married, Edith put all of her energy into art and teaching. Slope shouldered, with blue eyes and curly brown hair, Edith stood less than 5 foot 4 inches tall. She was known for her abundant energy and forthright manner, not quite a beauty, but certainly a great personality.

"She was brisk, not romantic," says Natalie Park Schutz."She had a huge sense of humor, a great big laugh-out-loud whoop; she called everyone 'boys.' She'd arrive for a visit and burst in calling out, 'Hi, boys, anyone here?'" One of Edith's favorite expressions was "corking."

"Boys, wasn't that speech of the president's corking!" she might say.

A born teacher, Edith returned periodically to the Boston Museum School as a lecturer. She also taught art and drama to children at The Park School, which operated in a brown 3 story house in Brookline where her older sister Julia had served as the principal since 1914. Edith and her sister Alice Park also worked at the school, and together the sisters were known to students as "the three Miss Parks." A 1921 photo from the Park School yearbook shows a serious looking 33 year old Edith wearing a white ruffled blouse, standing behind several rows of costumed students.

Edith Park Truesdell's oil portrait of her sister Julia still hangs at the Park School

In 1920, Edith had solo shows at the prestigious Copley Gallery in Boston, and the Denver Public Library. In the spring of 1922 "Miss Edith Park" exhibited a group of her watercolor paintings at an architectural school in Detroit. A reviewer commenting on the show of her watercolors noted: "The pictures (Watercolors) by Miss Park are rather free and summary in style, fresh and delicate in color with a good rendering of atmospheric qualities."

On March 21st of the same year, in a Boston ceremony, Edith Park married John Truesdell, an attorney based in Denver. Truesdell, a close friend of Edith's brother-in-law Ernest Knaebel, had come west in 1894. Highly educated, he had attended Philips Exeter Academy , and the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Originally trained as a civil engineer, Truesdell traveled west in the 1890s hoping mountain air would provide relief for his tuberculosis. In the 1890s he homesteaded a 2,173 acre tract of Colorado land on Bear Creek near Mt. Evans where he established a ranch. By 1903 Truesdell had earned his law degree at the University of Denver. Working for the Justice Department in Denver from 1912 onwards, he had gained a reputation as a champion of Indian rights and a "courageous" attorney. The newlywed Truesdells, who moved to Los Angeles in 1924, were known to their friends as "Jack and Edy."

Although Jack kept an office in Los Angeles, the Truesdells were often on the road, spending several months at a time in Arizona and Colorado. Later in her life, Edith painted many desert and mountain scenes inspired by her memories of these trips. In the early years of marriage Edith had several miscarriages, and the couple never had children.

From the moment that the Truesdells reached Los Angeles in 1924 Edith was active in the city's burgeoning art scene executing oils, watercolors and block prints. Edith took a first place in the 1925 Laguna Art Association show, and joined the California Art Club, showing work in the Club's annual exhibition from 1924 through 1932, and winning a gold medal in 1930. She also edited the CAC's bulletin between 1929 and 1931. She exhibited and came into contact with notable artists including Mabel Alvarez, Donna Schuster and Roger Schrader, members of the progressive "Group of Eight."

Writing about a 1927 solo show of Edith's work held at the University of California, Los Angeles Times critic Arthur Millier held up several of her works - including Sleeping Child, Old Timer and The Boss - for praise. Millier noted that Edith's paintings displayed "marked strength and beauty" and also commented that they "...show an unusually intelligent understanding of the art of space design and psychological effect of lines."

It was in 1928 that Edith's 17 year old nephew David Park - pulled from a boarding school at her insistence - drove west with her in a Model T to attend Otis Art Institute. He stayed with Jack and Edith in their home at 6310 Franklin Circle for only a short period, leaving for the Bay Area in the spring of 1929. David had been close to Edith growing up, and when he visited in 1928 he had the experience of her as a mature artist, living in a new environment, completely involved in making and exhibiting art.

Jack Truesdell retired from his position as Chief Field Counsel for the Indian Irrigation Service in 1934, and applied for a pension due to increasing health problems related to his tuberculosis. Because Edith was increasingly needed at the Ranch she gave up the teaching that she had been doing at the Winsor School for Girls in Brookline, Massachusetts in the winters of 1934 through 1936. However, that connection later helped her arrange a teaching job at the school for her nephew David, who headed the school's art department between 1936 and 1941.

After retirement, as the couple spent more time in Colorado, Jack's drinking became a problem. He was a binge drinker who was affectionate towards his "Dear Edy" when sober, but during his long periods of binging he was abusive and cruel. At least once, he threw her suitcases down the stairs and yelled "Get out!"

Edith made the most of her increasingly isolated living situation, and visits by friends and family - who found the Truesdell ranch a paradise - kept her spirits high. Her unmarried sister "Cad" Park was a frequent visitor, and she and Edith liked to dress in the same eccentric garb, which included knee socks and knickers. There was a croquet ground at the ranch as the game was a lifelong favorite of Edith's. There was also a room for painting, and during the war years Edith offered summer painting courses.

When David Park's young daughters Natalie and Helen came to visit in 1942, they found Edith in high spirits, a trooper who used humor to deal with difficulty. Natalie recalls:

"Edith had a little vegetable garden there, and was cooking some nice fresh beets in her pressure cooker; Edy, Helen and I were all in the kitchen when the pressure cooker gasket blew, and red inky water shot up, hit the white ceiling, made great splash marks all over it, dripped down on all of us. We all dropped our jaws and gaped, then Edith gave that whoop of a laugh. What a way to deal with disaster!"

During the war years, seeking escape and craving family, Edith would return to the east coast each winter, where she busied herself teaching painting both at the Waynflete School in Main, and at the Boston YMCA. In an article from the Christian Science Monitor dated January 9th, 1942, Edith discusses the positive effects of the art classes for "laymen" that she had been teaching at the YMCA on Clarendon Street in Boston. "Mrs. Truesdell's experience has been that her pupils find it not so much an escape from pressing duties as a restorative, a new side to life, a means toward fuller use of the faculties, and thus an aid to normalcy." That statement also describes precisely how Edith viewed the role of art in her own life.

On December 17, 1944, in a magazine published by the New York Times, Edith published an article titled "It May Not Be Art, But It's Fun." Exhorting Americans to take up the brush, the piece is filled by Edith's enthusiastic maxims: "So little is needed to make art part of our lives!" From her experiences in teaching art to beginners and amateurs Edith concludes that people who develop their "innate gift" for art will have "happier lives." The result, she feels, will be "...more people who will understand an important terrain of thought and feeling that now amounts to an enigma."

Edith briefly returned to the Winsor School for the 1943-44 and 1944-45 school years. In December of 1943 Director Frances Dorwin Dugan reported to the school's board: "After Christmas Edith Park Truesdell joins us for work in the Studio for four months, the only four months she can be in Boston. As some of you know, she is a distinguished and dynamic teacher of drawing and painting."

Later in her life, Edith told friends that between 1940 and Jack's death in 1953 she did not work on her own paintings. She continued to teach and in 1948 she designed and marketed original wallpapers. Writing in the Christian Science Monitor, reporter Hazel Henly recorded that "After years as an art teacher, helping others develop talents which, sometimes, they hadn't known they possessed, Mrs. Truesdell is tackling her new career with all the zest of a child let out of school." The same clipping, which notes that the artist's husband "cooperates" with her dedication to art, gives some insight into the state of the Truesdell's marriage:

"Although Mr. Truesdell, a lawyer who is now retired, does no painting himself, he has a keen interest in his wife's work, and especially enjoys her summer courses, held in the wagonshed on the ranch. One of his responsibilities, Mrs. Truesdell said, is to remind them all when it is dinnertime - a thing which artists, intent on their work, are apt to forget."

By 1948 Edith had given up her teaching and her trips to the East Coast to care for her ill husband. The couple bought a home in Englewood and sold their beloved ranch to the State of Colorado for creation of a Wildlife Management Area --with a provision for lifetime use of the main house. After Jack's death in 1953 Edith also deeded the ranch house itself to the Fish and Game Service, telling relatives that it held too many difficult memories for her.

Edith later told a Colorado biographical publication that at this point she had to decide "...whether to stay here in the house on Clarkson, or go back and join my sisters at the farm house in New England, or turn a new leaf and go somewhere else. I decided to try living along and concentrating on my painting - that's when I moved to California." Now 65, she arrived in California in a bright red MG convertible.

While searching for a place to live Edith rented a room in Berkeley and took classes at UC Berkeley while searching for a place to build a home. She eventually bought property on Mt. Tamalpais, a steep lot far above Mill Valley. To fit the shape of the lot, her new home was designed with triangular rooms, including a generous living room. It also had a broad deck for taking in the view. Edith living there for nearly 13 years, making and entertaining friends and family, writing poetry, collecting Mexican folk pottery, and painting; in acrylic rather than oil.

When David Park died after a painful struggle with bone cancer in 1960, Edith was devastated. Still, she was someone that handled life's tragedies with stoicism and resilience. In her diary, after David Park's death she wrote, simply; "David died last night, well, that's that." As Helen Park Bigelow sees it, Edith's diary entry is especially poignant as it "says what someone else might take pages to express."

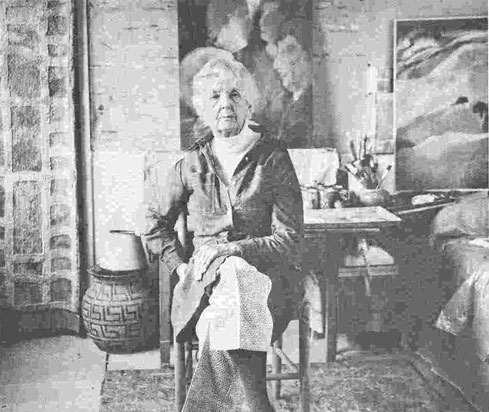

In 1963, determined not to be a burden to her nephews and nieces, Edith took a room at Carmel Valley Manor, a coastal retirement home. She immediately started a magazine, taught poetry, hung her paintings on the walls, and taught painting. She painted using acrylic on Masonite - or sometimes sheetrock -- laid flat across her bed.

Edith's most precious possessions, including Navajo baskets and the best of her paintings, were labeled with masking tape with the name of the person she wanted to have them. Since she lived to be 98, she out-lived most of the people they were intended for, and commented to friends on the "strangeness" of outliving so many members of her generation.

During the more than 20 years that Edith lived in Carmel, she worked hard to put her paintings in front of the public. She had solo shows at the Boston Museum School in 1970, and also at the Monterey Peninsula Museum in 1983. She participated in group shows with the Carmel Art League, had several shows at Gordon Newell's studio/gallery in Monterey, and also a one woman exhibition at the Pat Carey Gallery in 1979.

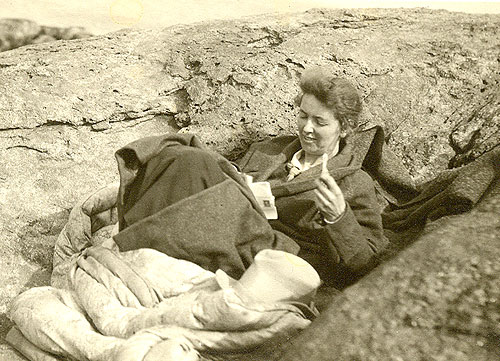

Edith paints on the floor in an undated photo

Despite all the exposure, her reputation remained local. "She always hoped to be discovered," says Natalie Park Schutz, "... still hopeful like a girl in her 80s, but her hopes faded in her 90s." To some degree, Edith may have been held back by modesty. "She never seemed to be selling herself as an artist," recalls Barbara Loeffler, a grand-niece.

Another thing that complicated Edith's career was her connection to David Park. On the one hand, he had paved the way for Bay Area Figurative art to be taken seriously as an alternative to Abstract Expressionism, but it hurt Edith that she was seen as his "follower" and not the other way around. Edith and David's paintings have a similar "energy" in Helen Park Bigelow's view, but she points out that "If there was ever anyone on earth that was totally her own person it was Edith. They did not borrow from each other; they looked long and thoughtfully at each others work during their shared years..." Many of Edith's late figurative paintings have a kind of shorthand that resembles that of David Park, but Edith also had a deep engagement with landscape painting, a subject that David had left alone.

Edith Park Truesdell's long lifeline runs parallel to that of the first American woman artist to achieve real fame; Georgia O'Keefe. Edith was born just four months later than O'Keefe, and outlived her by nine months. Perhaps with a different life script - for example if she had married an art dealer as O'Keefe did - Edith might have come to the end of her long life having received broader recognition as an artist. Edith's dedication to others, as a teacher, an aunt, and as a wife, also deflected her from the pursuit of fame. Selflessness was Edith Park Truesdell's strength; not self-promotion.

When Edith died in December of 1986, she had made sure that there would be no fuss. "She specifically requested no memorial," says Natalie Park Schutz, "Like David, she had made Neptune Society arrangements." Her "memorial" was the legacy of her paintings, scattered among her family and friends. She also left six paintings to decorate the reception area of Carmel Valley Manor.

"But oh boy! Did she make an impression," remembers Roger Cogswell, a relative, "She was so full of energy, so penetrating and so overpowering."

The Christian Science Monitor of January 9th, 1942 quotes some choice advice Edith gave to other women considering taking up art: "She believes that women should have no compunction about pursuing this artistic by-path, although it may seem merely a diversion in the midst of stern realities."

Edith Park Truesdell lived precisely by her own advice, with no complaints. She loved life too much to complain, and there was art to be made.

Below: A slideshow of paintings by Edith Park Truesdell