The single most beautiful and moving Abstract Expressionist painting I have ever seen is "Basel Mural I" by Sam Francis. I know, that is quite a strong statement, but I'll stand by it until I come across a painting I like better. I doubt that will happen anytime soon.

Painted between 1956 and 1958, "Basel Mural I" originally hung in a stairwell of the Kunsthalle Basel along with two companion pieces, "Basel Murals II and III." The group of paintings was broken up and disbursed in 1964.

In 1967, after some conservation work, "Basel Mural I" was donated by Francis to the Pasadena Art Museum, which later became the Norton Simon Museum. It now shares a room at the Simon with two vertical fragments of "Basel Mural III," -- which was re-stretched into 4 tall, separate panels after it was damaged during shipping -- while "Basel Mural II" which is intact, is 5,500 miles away in the collection of Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum. In other words, "Basel Mural I" is a survivor: one panel of a triptych that will never again be entirely whole.

"Basel Mural I" is a painting that never fails to touch me at a very deep level. Majestic in scale, measuring just under 13 feet tall and nearly 20 feet wide, its vivid blues, blazing oranges and golden yellows burn brightly in a white field that to me represents what art historian Kirk Varnedoe called "the white light of mysticism."

Sam Francis, "Basel Mural I," 1956-58

Oil on canvas, 151-3/4 x 237-3/8 in.

Norton Simon Museum, Gift of the Artist

© 2011 The Sam Francis Foundation/Artists Rights Society

Photo Credit: Kimberly Mackey

Gorgeous, seemingly alive, and resolutely abstract, "Basel Mural I," and the two other murals that once accompanied it, have their aesthetic roots in the vast, horizonless Monet "Nymphéas" installed on the lower floor of the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris. It also draws inspiration from Japanese art, one of Francis' lifelong preoccupations. Painted in oil, with some areas that have the transparency of watercolor, "Basel Mural I" is a painting that goes beyond its visual sources, and beyond the tangible, into something else entirely.

Trying to put into words -- in aesthetic and art historical terms -- just where it came from, where it went, and how it did so strikes me as a potentially frustrating and limited exercise. Simply calling the painting and the artist who made it "mystic" might be the best approach. Francis would have agreed: "The making of a painting has no past that can be traced," he once told an interviewer. "You can't trace it through the art history, through the forms and analysis and all that crap." Francis may have been in a bad mood when he said that, but I'll keep his words in mind, and write as well as I can despite the warning.

If you haven't seen the Basel Mural, you very likely don't know what Sam Francis was capable of at the height of his powers. When I was an art student in the late 1970s and early 1980s I remember seeing Sam Francis prints almost everywhere. Yes, works by Francis could be found in major American, European and Japanese art museums, and at the prestigious Andre Emmerich Gallery on 72nd Street in New York, but they could also be found in the tourist trap galleries on Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco alongside works by over-exposed artists like Salvador Dali, Peter Max and Leroy Neiman.

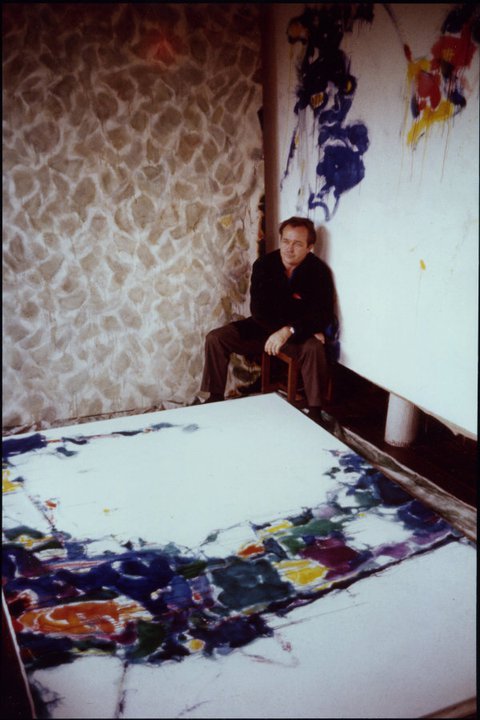

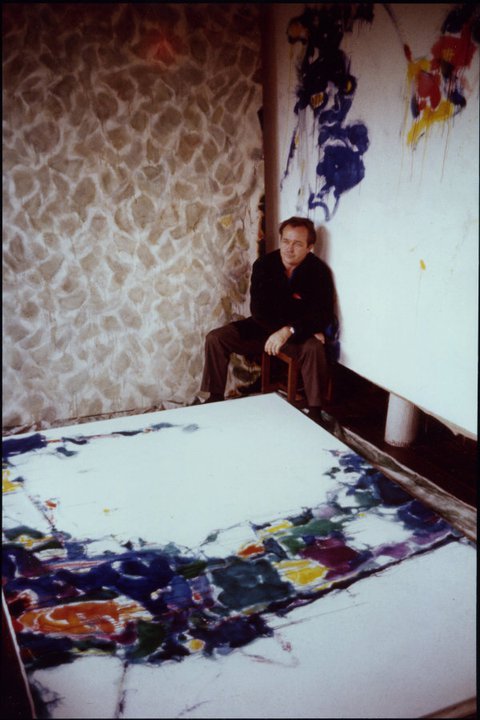

During a visit I made to Francis' Santa Monica studio with dealer Riko Mizuno in 1983, I was more impressed by the productive chaos of the place than I was by any of the paintings I saw. That experience reinforced the idea that Sam Francis knew how to make a lot of art and turn it into a lot of money, but I didn't yet understand the man's greatness.

The Basel Mural has served to re-educate me: Sam Francis was extraordinary.

Sam Francis in his Tokyo Studio, 1957

© 2011 The Sam Francis Foundation

"When Sam was good," says one of his lifetime friends, art dealer Paula Kirkeby, "he was very, very good." Critic Peter Plagens, writing in ArtForum in 1999 commented; "I've always thought the greatest Francises are easily better than the best Diebenkorns." "I've worked with lots of artists," master printer Jacob Samuel told the LA Times in 1995, "but nobody had what he (Francis) had." In a 2008 film by Jeffrey Perkins, "The Painter Sam Francis" art collector and museum director Pontus Hulten states that at one point in the 50s Francis was the most expensive living artist in the world, an amazing feat considering that Picasso was still alive at the time.

"Basel Mural I" strikes me as having a very full emotional range; from exultation to pain. Pain was certainly a constant in Francis' adult life. In fact, his career as an artist began with pain. While piloting an Air Force trainer over the Arizona desert in 1943 Francis ran out of gas and was badly injured in the crash that followed. He spent more than a year in the hospital recovering from spinal injuries, and experienced lifelong problems related to spinal tuberculosis. Francis was devastated that he never earned his Air Force wings, and that he was never able to become a Reconnaissance pilot as he had planned.

Learning to paint, initially with watercolors, was a way for Francis to cope with disappointment, intense boredom, injury and illness. "He painted to stay alive," says Debra Burchett-Lere, the Director of the Sam Francis Foundation.

Antoine de Saint-Exupery, the French writer and aviator wrote that "One of the miracles of the airplane is that it plunges a man directly into the heart of a mystery." Saint-Exupery, who wrote that after he, like Francis, walked away from an airplane crash, understood how flight transformed the modern psyche. Francis' son Shingo says that the freedom his father felt while painting related to the freedom and exhilaration he had felt while flying. I can't help thinking of Francis rising Phoenix-like in the decade after his accident, transformed from a medical student studying the rational sciences into an abstract artist pursuing the unknowable.

Peter Plagens has written metaphorically about Francis' paintings of the late 50's as pilot's-eye views over an ocean, characterizing them as "mural-sized canvases whose oceans of glaring white are interrupted by continents, islands, peninsulas, and isthmuses of intense blue, red, and yellow..." The website of the Norton Simon characterizes the fragments of "Basel Mural III" as containing "References to the sea and sun through radiant blues, oranges and yellows..." Francis himself wrote in his journal that the working on the Basel murals was like "doing huge sails dipped in color...They are like huge sails and I must be a strong wind for them."

A detail of "Basel Mural I"

© 2011 The Sam Francis Foundation/Artists Rights Society

Photo Credit: Kimberly Mackey

Although it is tempting to see the horizonless "Basel Mural I" that way -- as related to sails, islands and oceans -- I also feel strongly that it has something to do with experience of flight. "I have destroyed the ring of the horizon and got out of the circle of objects," exhorted the Russian abstractionist Kasmir Malevich, "Comrade aviators, sail on into the depths." That is the call that I think Francis was heeding, the lure of the depths of the unfathomable and the purely abstract.

The idea of a floating world, inspired by Monet's water lilies, gave Francis a visual threshold to cross. Aviation gave Francis the yin and yang of flight as the portal to mystery and also taught him about gravity, the enemy of flight. There is nothing like a crash in the desert to teach a young man the mortal power of gravity, or at least it seems that way to me. When I look at the drips and rivulets of "Basel Mural I" I feel the action of gravity pulling on its hovering brushstrokes.

Francis' use of bold, complimentary colors gives his "Basel Mural I" its dramatic counterbalance and also its considerable emotional tension. It should be noted that the complimentary colors scheme of the mural is reminiscent the way that Vincent Van Gogh punctuated his blue night skies with yellow and orange lights, stars and moons.

The philosopher and literary theorist Jean-Francois Lyotard, in his book "Sam Francis, Lesson of Darkness," states "Color evokes conflicting feelings in the artist: . . . color says to me: 'Come, I am your consolation, I cure your melancholy.'" Shingo Francis, an artist himself, remembers dropping by his father's studio after school and working on his own paintings. When Sam would comment on his son's canvasses, color was the central aspect of many of his critiques. Looking over his son's painting he would discuss "This yellow, this blue..." and so on.

As an adult, Shingo Francis has visited "Basel Mural I" and the two fragments of "Basel Mural III" at the Norton Simon, where they have made a strong impression. "There is a quality there that is very light and spacious," he says. Recalling the mood that the mural evoked as he approached it, Shingo Francis felt that its "melancholic blues" became "more and more intense: as you get into the room they are singing. The drips and blues and some of the red have the quality of sadness."

Sam Francis, "Basel Mural III Fragments," 1956-58

Oil on canvas, 152-5/8 x 40-1/4 in. and 152-5/8 x 43-5/8 in

Norton Simon Museum, Gift of the Artist

© 2011 The Sam Francis Foundation/Artists Rights Society

Photo Credit: Rob Corder

Shingo also recalls seeing the two verticals from "Basel Mural III" in the storage racks at his father's studio. "They were in his racks for years: he used to say it was really too bad that they were damaged in the shipment from New York in the hull of a ship." At the Norton Simon, two vertical sections of "Basel Mural III," donated to the Simon by the Sam Francis Foundation in 2009, are on display to the right of "Basel Mural I." "The strips in themselves are really beautiful," says Shingo Francis, but he also acknowledges that his father saw "Basel Mural III" as "something lost forever that will never come back."

Two other salvaged verticals cut from "Basel Mural III" were given by Francis to his friend, philanthropist Betty Freeman, who paid for the conservation of the Basel works. Those paintings remain in the estate of Freeman, who died in 2009.

When Sam Francis died in 1994, he left behind a huge trove of art, and a trail of personal tangles to sort out. "Sam was dark and light and loved complete chaos," says Paula Kirkeby.

Attorney Frederick Nicholas wrote that the artist, who had been married 5 times, was "highly organized in his work and unusually disorganized in his personal life." After a long, legal fight involving more than 10 attorneys and millions of dollars in legal fees, Francis' heirs were given their shares, and the remaining assets were left to establish the Sam Francis Foundation.

The Foundation, which was established to "research, document and perpetuate the creative legacy of Sam Francis," is on the verge of completing an important publication. Titled: "Sam Francis: Catalogue Raisonné of Canvas and Panel Paintings, 1946-1994," it will be issued by the University of California Press in October of this year.

The catalog will bring together a number of elements including:

Conceived as a kind of living document, the catalog will be regularly supplemented by electronic updates. An additional catalog of more than 5,000 prints and works on paper will be the Francis Foundation's next project. Of course, even as the catalogs are being issued, more images and more stories about Sam Francis are appearing. "Sam touched so many lives," comments Burchett-Lere.

If "Basel Mural I" is any indicator, the Sam Francis Catalogue Raisonné should hold some amazing revelations. Of course, if Francis were here he might not think too much of the words I have written here -- or of the words in the catalog -- but I am sure he would be pleased to know that a visual catalog of his vast output had been created. He would also certainly be pleased to know that some of us were at least taking the time to sit on the bench in front of "Basel Mural I" and soar with him once more.

Painted between 1956 and 1958, "Basel Mural I" originally hung in a stairwell of the Kunsthalle Basel along with two companion pieces, "Basel Murals II and III." The group of paintings was broken up and disbursed in 1964.

In 1967, after some conservation work, "Basel Mural I" was donated by Francis to the Pasadena Art Museum, which later became the Norton Simon Museum. It now shares a room at the Simon with two vertical fragments of "Basel Mural III," -- which was re-stretched into 4 tall, separate panels after it was damaged during shipping -- while "Basel Mural II" which is intact, is 5,500 miles away in the collection of Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum. In other words, "Basel Mural I" is a survivor: one panel of a triptych that will never again be entirely whole.

"Basel Mural I" is a painting that never fails to touch me at a very deep level. Majestic in scale, measuring just under 13 feet tall and nearly 20 feet wide, its vivid blues, blazing oranges and golden yellows burn brightly in a white field that to me represents what art historian Kirk Varnedoe called "the white light of mysticism."

Oil on canvas, 151-3/4 x 237-3/8 in.

Norton Simon Museum, Gift of the Artist

© 2011 The Sam Francis Foundation/Artists Rights Society

Photo Credit: Kimberly Mackey

Gorgeous, seemingly alive, and resolutely abstract, "Basel Mural I," and the two other murals that once accompanied it, have their aesthetic roots in the vast, horizonless Monet "Nymphéas" installed on the lower floor of the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris. It also draws inspiration from Japanese art, one of Francis' lifelong preoccupations. Painted in oil, with some areas that have the transparency of watercolor, "Basel Mural I" is a painting that goes beyond its visual sources, and beyond the tangible, into something else entirely.

Trying to put into words -- in aesthetic and art historical terms -- just where it came from, where it went, and how it did so strikes me as a potentially frustrating and limited exercise. Simply calling the painting and the artist who made it "mystic" might be the best approach. Francis would have agreed: "The making of a painting has no past that can be traced," he once told an interviewer. "You can't trace it through the art history, through the forms and analysis and all that crap." Francis may have been in a bad mood when he said that, but I'll keep his words in mind, and write as well as I can despite the warning.

If you haven't seen the Basel Mural, you very likely don't know what Sam Francis was capable of at the height of his powers. When I was an art student in the late 1970s and early 1980s I remember seeing Sam Francis prints almost everywhere. Yes, works by Francis could be found in major American, European and Japanese art museums, and at the prestigious Andre Emmerich Gallery on 72nd Street in New York, but they could also be found in the tourist trap galleries on Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco alongside works by over-exposed artists like Salvador Dali, Peter Max and Leroy Neiman.

During a visit I made to Francis' Santa Monica studio with dealer Riko Mizuno in 1983, I was more impressed by the productive chaos of the place than I was by any of the paintings I saw. That experience reinforced the idea that Sam Francis knew how to make a lot of art and turn it into a lot of money, but I didn't yet understand the man's greatness.

The Basel Mural has served to re-educate me: Sam Francis was extraordinary.

"When Sam was good," says one of his lifetime friends, art dealer Paula Kirkeby, "he was very, very good." Critic Peter Plagens, writing in ArtForum in 1999 commented; "I've always thought the greatest Francises are easily better than the best Diebenkorns." "I've worked with lots of artists," master printer Jacob Samuel told the LA Times in 1995, "but nobody had what he (Francis) had." In a 2008 film by Jeffrey Perkins, "The Painter Sam Francis" art collector and museum director Pontus Hulten states that at one point in the 50s Francis was the most expensive living artist in the world, an amazing feat considering that Picasso was still alive at the time.

"Basel Mural I" strikes me as having a very full emotional range; from exultation to pain. Pain was certainly a constant in Francis' adult life. In fact, his career as an artist began with pain. While piloting an Air Force trainer over the Arizona desert in 1943 Francis ran out of gas and was badly injured in the crash that followed. He spent more than a year in the hospital recovering from spinal injuries, and experienced lifelong problems related to spinal tuberculosis. Francis was devastated that he never earned his Air Force wings, and that he was never able to become a Reconnaissance pilot as he had planned.

Learning to paint, initially with watercolors, was a way for Francis to cope with disappointment, intense boredom, injury and illness. "He painted to stay alive," says Debra Burchett-Lere, the Director of the Sam Francis Foundation.

Antoine de Saint-Exupery, the French writer and aviator wrote that "One of the miracles of the airplane is that it plunges a man directly into the heart of a mystery." Saint-Exupery, who wrote that after he, like Francis, walked away from an airplane crash, understood how flight transformed the modern psyche. Francis' son Shingo says that the freedom his father felt while painting related to the freedom and exhilaration he had felt while flying. I can't help thinking of Francis rising Phoenix-like in the decade after his accident, transformed from a medical student studying the rational sciences into an abstract artist pursuing the unknowable.

Peter Plagens has written metaphorically about Francis' paintings of the late 50's as pilot's-eye views over an ocean, characterizing them as "mural-sized canvases whose oceans of glaring white are interrupted by continents, islands, peninsulas, and isthmuses of intense blue, red, and yellow..." The website of the Norton Simon characterizes the fragments of "Basel Mural III" as containing "References to the sea and sun through radiant blues, oranges and yellows..." Francis himself wrote in his journal that the working on the Basel murals was like "doing huge sails dipped in color...They are like huge sails and I must be a strong wind for them."

© 2011 The Sam Francis Foundation/Artists Rights Society

Photo Credit: Kimberly Mackey

Although it is tempting to see the horizonless "Basel Mural I" that way -- as related to sails, islands and oceans -- I also feel strongly that it has something to do with experience of flight. "I have destroyed the ring of the horizon and got out of the circle of objects," exhorted the Russian abstractionist Kasmir Malevich, "Comrade aviators, sail on into the depths." That is the call that I think Francis was heeding, the lure of the depths of the unfathomable and the purely abstract.

The idea of a floating world, inspired by Monet's water lilies, gave Francis a visual threshold to cross. Aviation gave Francis the yin and yang of flight as the portal to mystery and also taught him about gravity, the enemy of flight. There is nothing like a crash in the desert to teach a young man the mortal power of gravity, or at least it seems that way to me. When I look at the drips and rivulets of "Basel Mural I" I feel the action of gravity pulling on its hovering brushstrokes.

Francis' use of bold, complimentary colors gives his "Basel Mural I" its dramatic counterbalance and also its considerable emotional tension. It should be noted that the complimentary colors scheme of the mural is reminiscent the way that Vincent Van Gogh punctuated his blue night skies with yellow and orange lights, stars and moons.

The philosopher and literary theorist Jean-Francois Lyotard, in his book "Sam Francis, Lesson of Darkness," states "Color evokes conflicting feelings in the artist: . . . color says to me: 'Come, I am your consolation, I cure your melancholy.'" Shingo Francis, an artist himself, remembers dropping by his father's studio after school and working on his own paintings. When Sam would comment on his son's canvasses, color was the central aspect of many of his critiques. Looking over his son's painting he would discuss "This yellow, this blue..." and so on.

As an adult, Shingo Francis has visited "Basel Mural I" and the two fragments of "Basel Mural III" at the Norton Simon, where they have made a strong impression. "There is a quality there that is very light and spacious," he says. Recalling the mood that the mural evoked as he approached it, Shingo Francis felt that its "melancholic blues" became "more and more intense: as you get into the room they are singing. The drips and blues and some of the red have the quality of sadness."

Oil on canvas, 152-5/8 x 40-1/4 in. and 152-5/8 x 43-5/8 in

Norton Simon Museum, Gift of the Artist

© 2011 The Sam Francis Foundation/Artists Rights Society

Photo Credit: Rob Corder

Shingo also recalls seeing the two verticals from "Basel Mural III" in the storage racks at his father's studio. "They were in his racks for years: he used to say it was really too bad that they were damaged in the shipment from New York in the hull of a ship." At the Norton Simon, two vertical sections of "Basel Mural III," donated to the Simon by the Sam Francis Foundation in 2009, are on display to the right of "Basel Mural I." "The strips in themselves are really beautiful," says Shingo Francis, but he also acknowledges that his father saw "Basel Mural III" as "something lost forever that will never come back."

Two other salvaged verticals cut from "Basel Mural III" were given by Francis to his friend, philanthropist Betty Freeman, who paid for the conservation of the Basel works. Those paintings remain in the estate of Freeman, who died in 2009.

When Sam Francis died in 1994, he left behind a huge trove of art, and a trail of personal tangles to sort out. "Sam was dark and light and loved complete chaos," says Paula Kirkeby.

Attorney Frederick Nicholas wrote that the artist, who had been married 5 times, was "highly organized in his work and unusually disorganized in his personal life." After a long, legal fight involving more than 10 attorneys and millions of dollars in legal fees, Francis' heirs were given their shares, and the remaining assets were left to establish the Sam Francis Foundation.

The Foundation, which was established to "research, document and perpetuate the creative legacy of Sam Francis," is on the verge of completing an important publication. Titled: "Sam Francis: Catalogue Raisonné of Canvas and Panel Paintings, 1946-1994," it will be issued by the University of California Press in October of this year.

The catalog will bring together a number of elements including:

- An essay by art historian William Agee

- A biographical timeline compiled by Debra Burchett-Lere

- A searchable DVD of over 1,850 images, many of them "zoomable," supported by documentary images and photos

- A 2nd DVD with 2 films of Francis, a photo album and additional essays

Conceived as a kind of living document, the catalog will be regularly supplemented by electronic updates. An additional catalog of more than 5,000 prints and works on paper will be the Francis Foundation's next project. Of course, even as the catalogs are being issued, more images and more stories about Sam Francis are appearing. "Sam touched so many lives," comments Burchett-Lere.

If "Basel Mural I" is any indicator, the Sam Francis Catalogue Raisonné should hold some amazing revelations. Of course, if Francis were here he might not think too much of the words I have written here -- or of the words in the catalog -- but I am sure he would be pleased to know that a visual catalog of his vast output had been created. He would also certainly be pleased to know that some of us were at least taking the time to sit on the bench in front of "Basel Mural I" and soar with him once more.