"Humanity is not something man simply has. He must fight for it anew in every generation, and he may lose his fight." - Paul Tillich

The last time that San Francisco's John Berggruen Gallery opened a Nathan Oliveira exhibition it seemed like the world was about to come to an end. "Singular," an exhibition of Oliveira paintings dedicated to the painter Balthus opened on September 12, 2001, a day after the calamitous terror attacks of September 11th plunged America, and the world, into shock, grief, and uncertainty.

On the day of the opening, people lingered in front of Oliveira's canvases of lithe, isolated figures, described in the catalog as "...moving gracefully about in their private worlds," and talked about their renewed fears for the future. At a time when Oliveira, then 72, should have been able to enjoy his commercial and critical success -- "Singular" was a sold out show -- the images of 9/11 and its aftermath threw him into a deep personal and creative funk.

For Oliveira, a lifelong pacifist who had made anti-war posters during the Viet Nam era, the senseless loss and destruction was a direct assault on his hopes for the world. A father of 3, and a college art professor for a total of 34 years, Oliveira was a nurturing man who took people under his wing, improving the world one person at a time. "He helped so many people," remembers his son Joe. "He was all about humanity, and he painted from his heart and from his soul."

When a traveling retrospective of his work opened at the Neuberger Museum of Art opened ten months later the recognition helped to renew his sense of mission. Before long he was back in the studio, trying to search out a new stream of images that could channel his emotions. Near the end of 2002 a trickle of works began to appear, including "Runner," a large oil painting that shows a fleeing figure inspired by the haunting news images of New Yorkers racing from the inferno of the twin towers. "All I can remember of that fateful day, " Oliveira told art historian Dore Ashton, "aside from the terror of the buildings collapsing, was that I saw a lot of people running."

The ashen palette of "Runner" and its theme of flight contrast starkly with the rust and violet reverie of "Cobalt Dancer" from the year before. 9/11 had shaken the world outside, and it changed Oliveira on the inside. "Oliveira's works are always drawn from himself," notes Dore Ashton, and his late works would be no exception.

A side by side of Oliveira paintings created before and after the 9/11 attacks.

Left: Nathan Oliveira, "Cobalt Dancer," 2001, oil, alkyd & wax on canvas, 84 x 70 inches

Right: Nathan Oliveira, "Runner," 2002, oil on canvas, 84 x 70 inches

The few canvases that Oliveira produced in 2003 and 2004 had themes that suggested a regaining of equilibrium. They include a skater, some paintings of intertwined couples walking, and also a series of "Rockers." The rockers, who balance on graceful curved skids, are about "...those that simply move back and forth and never really get anywhere no matter what they are attempting." Composed of red and earthen hues inspired by the deserts of the American Southwest, the rockers emerge from environments created with translucent washes of oil pigments modified with alkyd resins. Color, which Oliveira often spoke of as a kind of food, was his means of transmitting deep emotions, and also of recharging himself.

Nathan Oliveira, "Red Rocker #1," Oil and alkyd on canvas, 84 x 70 inches

Painting came to a halt in late 2004 when Oliveira required heart valve replacement surgery. Then, in 2005 Mona Oliveira was diagnosed with cancer. Nathan devoted himself to caring for her during her illness, and together they talked about their shared dream of establishing a meditation center on the Stanford Campus, to be filled with the soaring images of Nathan's Windhover paintings. That project, which is now in the late stages of planning, came from the couple's conviction that the world needs more places for quiet rest and contemplation.

When Mona died the following year, after 56 years of marriage, Nathan lost his anchor. "They were so great to be around," recalls painter Roy Borrone, a family friend. "He was a great storyteller, but when he exaggerated she corrected. Mona was so strong for him, and she when it came to his art she was the only critic he listened to."

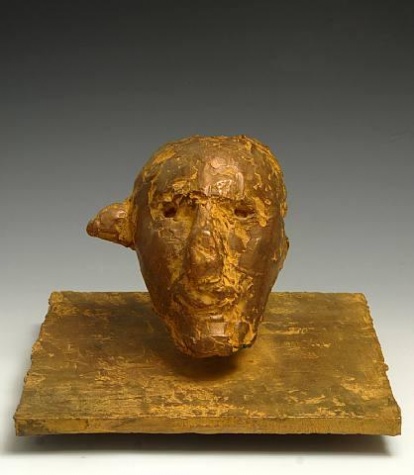

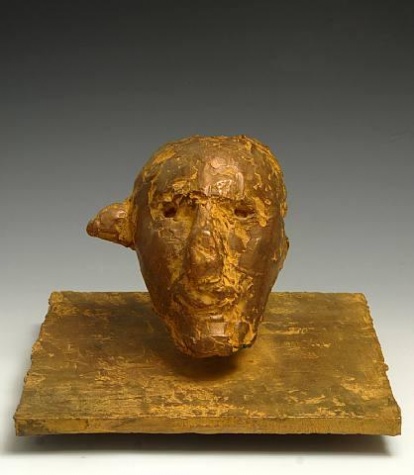

After Mona's death, the couple's son Joe stepped in to help around the house and also in the studio. Nathan wasn't feeling like painting. "Then," says Joe, " I put some clay in front of him," Oliveira went on to create a series of small masks, later cast in bronze and patinated in earthen shades. "They speak of deeply felt grief and of that forbidden subject in our culture, death," wrote curator Signe Mayfield when they were shown in 2008 as part of retrospective of Oliveira's works in bronze.

Nathan Oliveira, Mask VI, 2007, bronze with custom patina, approx. 7 3/4 inches high

By 2008 pulmonary fibrosis required the artist to rely on an oxygen tank much of the time, and other health problems, including diabetes, and low blood sugar took their toll. After a fall, Oliveira broke his left elbow, requiring a titanium insert, and there were scary moments when he felt himself barely able to breathe. Despite the setbacks, Oliveira never lost his sense of humor. "He was such a magical guy," says Roy Borrone, "and so fun to be around."

In the last year and half of Oliveira's life, there were wonderful developments in the studio. "The old Nathan came back," says Joe Oliveira, "the guy who wanted to be in the studio every day. He couldn't wait to get back in there; something new and beautiful was happening." Starting with rich, abstract washes of color, Oliveira was again inspired to conjure up haunting, solitary figures. Working on several paintings at a time, the finished works began to add up: first 10, then 12, then 15 large paintings with dreamy translucent atmospheres. There were also small, softly brushed portraits with pensive expressions.

It was also a time of friendship. Oliveira greatly enjoyed visits from old friends, visiting artists, and former students. He took great pleasure in his lunches at the Stanford Faculty Club, and the sumptuous dinners at Marché in Menlo Park. Roy Borrone remembers that Nathan loved "...his lamb chops, his martinis and all the pretty women who walked by."

Applying a wash, late 2010

With his friend and fellow artist William Theophilus Brown, 2010

Of course it wasn't all smooth sailing: one 8 foot wide canvas had its figure re-painted 7 times before Nathan eliminated the figure entirely and covered it with a complicated "site" image that was left unfinished at his death. Oliveira also began to question his continuing reliance on the human figure, something that art critics had chided him about over the years. More than once he complained to Joe, "I'm tired of these damned figures." Despite the many others subjects he had developed over the years -- including images of animals, semi-abstract sites, and visionary images of flight -- the human figure was Oliveira's touchstone; a primary vehicle for the dialogue that his art required. "They are images that I can interact with," Oliveira said of his figures in an interview just 10 days before his death.

In his final months Oliveira was also very aware of his own mortality, and at one he had a talk with Joe to let him know that it wouldn't be too long before he left for the "big studio in the sky." Still, on his good days he was doing so well that Joe Oliveira was sure his father would make it to his wedding, planned for June of 2011. "Nate was invigorated," Joe says, "He was one of the lucky ones: he had his passion."

"Even with his oxygen mask and his knee trouble he was squatting down and working on canvasses set on 4" x 4" blocks on the floor," says Roy Borrone. "He would get excited about a painting, and then the next day he would turn the figure around. It was amazing how well he could draw, and he could re-paint things so quickly and easily."

Nathan Oliveira, with his Rottweiler Rocky in a final studio shot, October 2010

On Saturday, November 13th, 2010, Oliveira spoke to Joe's fiancée Melissa on the telephone and told her that he had finished a painting. It wasn't often that he told someone that, as he had a tendency to keep going back over most of what he did. That evening, after dinner and drinks with friends, Nathan Oliveira retired to his bedroom one last time. He was found there the next morning, guarded by his dog Rocky.

On the other end of the house, leaning against walls and resting on easels was a new family of human figures, both male and female, running, striding or simply looming. When he entered Oliveira's studio several weeks after the artist's death, dealer John Berggruen found himself "...completely taken aback by the scope and beauty of the work he (Nathan) had completed since my previous visit."

Those paintings, assembled in Nathan's Memorial show along with a selection of earlier bronzes and drawings, are Nathan Oliveira's final visions. They embody the qualities that he was seeking all his life: beauty, timelessness, and mystery. They seem to belong to another world, just beyond what can be put into words.

Nathan Oliveira: A Memorial Exhibition

Opening reception: Thursday, September 8th from 5:30-7:30pm

John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco

September 8 - October 22, 2011

www.berggruen.com

The last time that San Francisco's John Berggruen Gallery opened a Nathan Oliveira exhibition it seemed like the world was about to come to an end. "Singular," an exhibition of Oliveira paintings dedicated to the painter Balthus opened on September 12, 2001, a day after the calamitous terror attacks of September 11th plunged America, and the world, into shock, grief, and uncertainty.

On the day of the opening, people lingered in front of Oliveira's canvases of lithe, isolated figures, described in the catalog as "...moving gracefully about in their private worlds," and talked about their renewed fears for the future. At a time when Oliveira, then 72, should have been able to enjoy his commercial and critical success -- "Singular" was a sold out show -- the images of 9/11 and its aftermath threw him into a deep personal and creative funk.

For Oliveira, a lifelong pacifist who had made anti-war posters during the Viet Nam era, the senseless loss and destruction was a direct assault on his hopes for the world. A father of 3, and a college art professor for a total of 34 years, Oliveira was a nurturing man who took people under his wing, improving the world one person at a time. "He helped so many people," remembers his son Joe. "He was all about humanity, and he painted from his heart and from his soul."

When a traveling retrospective of his work opened at the Neuberger Museum of Art opened ten months later the recognition helped to renew his sense of mission. Before long he was back in the studio, trying to search out a new stream of images that could channel his emotions. Near the end of 2002 a trickle of works began to appear, including "Runner," a large oil painting that shows a fleeing figure inspired by the haunting news images of New Yorkers racing from the inferno of the twin towers. "All I can remember of that fateful day, " Oliveira told art historian Dore Ashton, "aside from the terror of the buildings collapsing, was that I saw a lot of people running."

The ashen palette of "Runner" and its theme of flight contrast starkly with the rust and violet reverie of "Cobalt Dancer" from the year before. 9/11 had shaken the world outside, and it changed Oliveira on the inside. "Oliveira's works are always drawn from himself," notes Dore Ashton, and his late works would be no exception.

A side by side of Oliveira paintings created before and after the 9/11 attacks.

Left: Nathan Oliveira, "Cobalt Dancer," 2001, oil, alkyd & wax on canvas, 84 x 70 inches

Right: Nathan Oliveira, "Runner," 2002, oil on canvas, 84 x 70 inches

The few canvases that Oliveira produced in 2003 and 2004 had themes that suggested a regaining of equilibrium. They include a skater, some paintings of intertwined couples walking, and also a series of "Rockers." The rockers, who balance on graceful curved skids, are about "...those that simply move back and forth and never really get anywhere no matter what they are attempting." Composed of red and earthen hues inspired by the deserts of the American Southwest, the rockers emerge from environments created with translucent washes of oil pigments modified with alkyd resins. Color, which Oliveira often spoke of as a kind of food, was his means of transmitting deep emotions, and also of recharging himself.

Painting came to a halt in late 2004 when Oliveira required heart valve replacement surgery. Then, in 2005 Mona Oliveira was diagnosed with cancer. Nathan devoted himself to caring for her during her illness, and together they talked about their shared dream of establishing a meditation center on the Stanford Campus, to be filled with the soaring images of Nathan's Windhover paintings. That project, which is now in the late stages of planning, came from the couple's conviction that the world needs more places for quiet rest and contemplation.

When Mona died the following year, after 56 years of marriage, Nathan lost his anchor. "They were so great to be around," recalls painter Roy Borrone, a family friend. "He was a great storyteller, but when he exaggerated she corrected. Mona was so strong for him, and she when it came to his art she was the only critic he listened to."

After Mona's death, the couple's son Joe stepped in to help around the house and also in the studio. Nathan wasn't feeling like painting. "Then," says Joe, " I put some clay in front of him," Oliveira went on to create a series of small masks, later cast in bronze and patinated in earthen shades. "They speak of deeply felt grief and of that forbidden subject in our culture, death," wrote curator Signe Mayfield when they were shown in 2008 as part of retrospective of Oliveira's works in bronze.

By 2008 pulmonary fibrosis required the artist to rely on an oxygen tank much of the time, and other health problems, including diabetes, and low blood sugar took their toll. After a fall, Oliveira broke his left elbow, requiring a titanium insert, and there were scary moments when he felt himself barely able to breathe. Despite the setbacks, Oliveira never lost his sense of humor. "He was such a magical guy," says Roy Borrone, "and so fun to be around."

In the last year and half of Oliveira's life, there were wonderful developments in the studio. "The old Nathan came back," says Joe Oliveira, "the guy who wanted to be in the studio every day. He couldn't wait to get back in there; something new and beautiful was happening." Starting with rich, abstract washes of color, Oliveira was again inspired to conjure up haunting, solitary figures. Working on several paintings at a time, the finished works began to add up: first 10, then 12, then 15 large paintings with dreamy translucent atmospheres. There were also small, softly brushed portraits with pensive expressions.

It was also a time of friendship. Oliveira greatly enjoyed visits from old friends, visiting artists, and former students. He took great pleasure in his lunches at the Stanford Faculty Club, and the sumptuous dinners at Marché in Menlo Park. Roy Borrone remembers that Nathan loved "...his lamb chops, his martinis and all the pretty women who walked by."

Applying a wash, late 2010

Of course it wasn't all smooth sailing: one 8 foot wide canvas had its figure re-painted 7 times before Nathan eliminated the figure entirely and covered it with a complicated "site" image that was left unfinished at his death. Oliveira also began to question his continuing reliance on the human figure, something that art critics had chided him about over the years. More than once he complained to Joe, "I'm tired of these damned figures." Despite the many others subjects he had developed over the years -- including images of animals, semi-abstract sites, and visionary images of flight -- the human figure was Oliveira's touchstone; a primary vehicle for the dialogue that his art required. "They are images that I can interact with," Oliveira said of his figures in an interview just 10 days before his death.

In his final months Oliveira was also very aware of his own mortality, and at one he had a talk with Joe to let him know that it wouldn't be too long before he left for the "big studio in the sky." Still, on his good days he was doing so well that Joe Oliveira was sure his father would make it to his wedding, planned for June of 2011. "Nate was invigorated," Joe says, "He was one of the lucky ones: he had his passion."

"Even with his oxygen mask and his knee trouble he was squatting down and working on canvasses set on 4" x 4" blocks on the floor," says Roy Borrone. "He would get excited about a painting, and then the next day he would turn the figure around. It was amazing how well he could draw, and he could re-paint things so quickly and easily."

On Saturday, November 13th, 2010, Oliveira spoke to Joe's fiancée Melissa on the telephone and told her that he had finished a painting. It wasn't often that he told someone that, as he had a tendency to keep going back over most of what he did. That evening, after dinner and drinks with friends, Nathan Oliveira retired to his bedroom one last time. He was found there the next morning, guarded by his dog Rocky.

On the other end of the house, leaning against walls and resting on easels was a new family of human figures, both male and female, running, striding or simply looming. When he entered Oliveira's studio several weeks after the artist's death, dealer John Berggruen found himself "...completely taken aback by the scope and beauty of the work he (Nathan) had completed since my previous visit."

Those paintings, assembled in Nathan's Memorial show along with a selection of earlier bronzes and drawings, are Nathan Oliveira's final visions. They embody the qualities that he was seeking all his life: beauty, timelessness, and mystery. They seem to belong to another world, just beyond what can be put into words.

Nathan Oliveira: A Memorial Exhibition

Opening reception: Thursday, September 8th from 5:30-7:30pm

John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco

September 8 - October 22, 2011

www.berggruen.com