In the Fall of 1981 I was an incoming graduate student in Painting at UC Berkeley, anxious to meet my new professors including the respected Bay Area Figurative artists Elmer Bischoff and Joan Brown. Because I was so intent on getting Brown's opinion of my work I scheduled an individual critique with Joan, and installed a recent 7 by 9 foot canvas in UCB's downstairs gallery especially for her viewing.

Joan arrived promptly, a striking woman with piercing eyes accented by heavy mascara and bright hennaed hair. She immediately made stinging observations about my work, which was titled "Dead Duck." She told me that my painting -- a cartoonish canvas depicting a duck being shot out of the sky -- was incoherent, impossible to respect, and lacking in focus. No teacher had ever spoken to me that way before.

Stunned, I asked Joan if there wasn't anything she liked about the work. I will never forget her response, which she made in a raised voice as she stormed out of the gallery:

"You need your ass kicked."

Although I later took Brown's class and saw her softer side, that first impression has lingered with me for 30 years. Brown, in her words and in her art, was uncompromisingly assertive. Her toughness didn't endear her to everyone, but over the long haul it was the quality that distanced her from a difficult childhood and moved her towards the visionary optimism that characterized her final works.

Joan Brown, "Self-Portrait with a Scarf," 1972, enamel on canvas, 16 x 12 inches

Collection of Wanda Kownacki and John Holton

Jodi Throckmorton, an Associate Curator at the San Jose Museum of Art, and the organizer of "This Kind of Bird Flies Backward: Paintings by Joan Brown," says that Brown was a strong, original individual who avoided ideology. Although often seen as a feminist, Brown's life and art fall into a kind of "grey area of feminism" according to Throckmorton. "Her apolitical approach to the subjects of domesticity, gender, aging, relationships, and motherhood may be the cause of her exclusion," Throckmorton writes, "nonetheless, time has shown that her choices as a woman and as an artist were anything but neutral."

The title of the San Jose exhibition is taken from the title poem of Diane di Prima's "This Kind of Bird Flies Backwards," and was chosen because Brown and di Prima -- a rare female beat poet who used street language -- seem like kindred spirits. Both were women who uncompromisingly made there way into male dominated fields while struggling to maintain their identities as women. Adele Landis Bischoff, whose husband Elmer was an important mentor to Brown in the late 50's recalls that Brown was indeed a tough young "bird."

"Early on, when I met her, she was like a young -- if a rooster can be female -- she was like a rooster," says Landis.

Brown's biographer, Karen Tsujimoto, puts it this way: "In her art she had no one whom she had to answer to or to be responsible for, and she relished and protected this freedom fiercely." Joan was an artist and an individual first. "I can't do without making pictures of my own," she once commented, "And I don't know why this is so. But it's true..."

Brown's toughness was, in fact, the result of a childhood that was emotionally claustrophobic. The only child of an alcoholic father and a mother who often threatened to jump off the Golden Gate bridge and who eventually did take her own life in 1969, Joan later recalled her early years as being "...dark, I mean dark in the psychological way." She was anxious to grow up quickly; "All I wanted to do was grow up and get the hell out of there." Joan Beattie graduated from high school a self-proclaimed "con artist" who knew when she could get away with things, and when to fade into the woodwork.

Bill and Joan Brown, by C.R. Snyder, from the film "San Francisco's Wild History Groove"

Photo courtesy filmmaker Mary Kerr.

Seventeen year old Joan's life pivoted when she noticed an advertisement for the California School of Fine Arts, which she decided to attend instead of the Catholic college her parents had in mind. Entering in 1955, she fell in love with the beatnik atmosphere of the school: bongo drums playing in the halls, guys with long hair, beards and sandals. Bright and charismatic, she immediately attracted male attention. "I have this extraordinary student," Elmer Bischoff told his colleague Wally Hedrick, "She's either a genius or very simple." In her first year at CSFA Joan married her first husband, painter Bill Brown, met important artistic mentors including Bischoff and Frank Lobdell, and also connected with another student, Manuel Neri, who would be her second husband and the father of her son Noel.

Brown's student paintings were "clumsy" and she became something of a school legend because she was always covered with paint from head to toe. Moving back and forth between abstraction and figuration, she gradually developed a representational style that had a kinship with the "Bay Area Figurative Style" championed by several of her male instructors. Brown didn't feel held back by being a woman: in a sense she was one of the guys, and later remembered being "supported like hell" by the men who surrounded her.

In 1959 her paintings caught the attention of visiting lecturer David Park who said "I just love these paintings." Her mentor Elmer Bischoff felt differently -- "I can't stand them" was his comment -- but her thickly painted works had an affinity with Park's late canvases. It was Park's dealer, visiting from New York who dropped by Brown's studio by accident in 1959, paid $300 for 2 of her paintings and launched her career. Brown was so convinced that the check was fake, that she took it to her father, a bank employee, to see if it was real.

By 1962 Brown, now married to Manuel Neri and about to become a mother, had shown in New York and at the Whitney Museum. A 1961 trip to Europe with Neri had opened her eyes to Goya, Velasquez, Rembrandt and other masters, and she had a great studio relationship with her new husband, a sculptor. Unfortunately, she would later recall, the studio was the only place they ever got along.

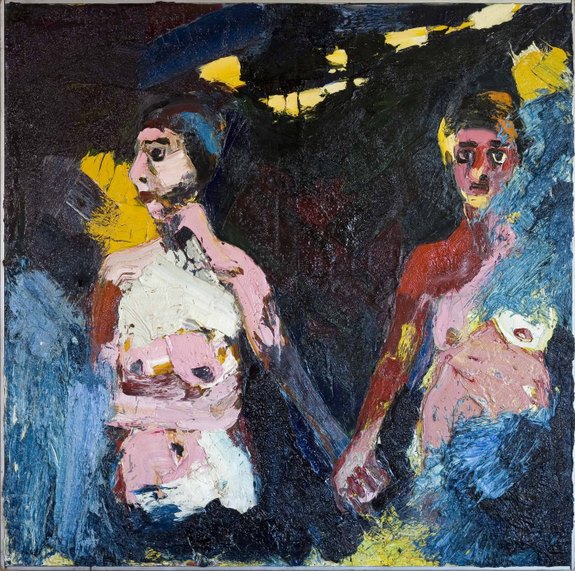

A 1962 painting on view at San Jose, "Brown Girls in the Surf with Moon Casting a Shadow," shows the "cacophany of pure color and energy" that Brown could generate. The encrusted, ragged slabs of pigment, achieved with inexpensive "Bay City Paints" poured from one gallon cans have some of the craggy abstract energy of Clyfford Still, but the poetry and tenderness of the image was Brown's alone. She had borrowed her subject matter -- nudes by the water -- from Park and Bischoff, and reconstituted them with a helping of gentle, slapdash parody. Bischoff's nudes of the early 60s have a Wagnerian seriousness about them, while Brown's figures are ice cream sundaes in paint, with a cherry on top.

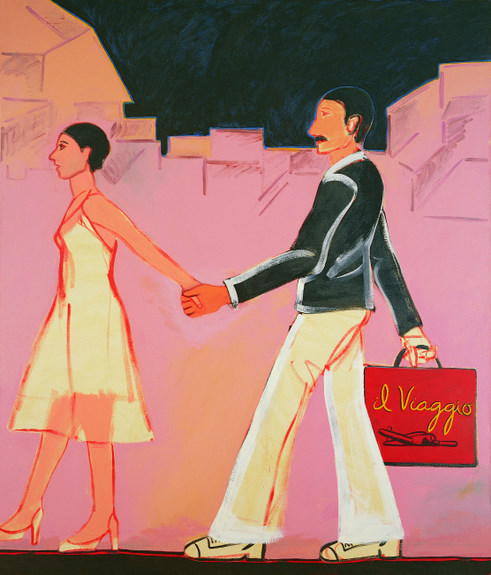

Driven by her need to tell stories, Brown's style moved over time towards illustration, and thinly brushed lines of enamel began to supplant and replace the heavy, troweled applications of oil paint. Because her career had been launched by imitating the styles of older artists who had already rebelled, Brown had never mastered traditional rendering, and she was to some degree always a naive painter. Recognizing this she took to heart the example of Henri Rousseau and let stylization, narration and a dose of Egyptian stiffness carry her work. In "The Journey, #1" she appears leading a lover forward in an frieze-like composition; it's clear who is in charge. Like many of her best paintings, the image is crisp, smart and engaging.

Brown was a prolific maker of self-portraits that broadcast her considerable emotional range and also her social observations. Her densely patterned 1977 "Self-Portrait," which has been said to "call into question the stereotypical image of the female artist," demonstrates that Joan's way of exploring the role of women was to start from her personal experience. It also seems like a transitional painting in which an artist seeking clarity and order rises above the mess that covers her floor. Sure enough, within a few short years Brown's art and imagery would enter a distinctive new phase.

A 1980 trip to India with her 4th husband, SFPD officer Michael Hebel, brought her into contact with Sai Sathya Baba, a yogic guru who insisted on the divine nature of all men and women. When Sai Baba briefly made direct eye contact with Brown during a blessing ceremony at his ashram, she later told friends that she had developed a red third eye on her forehead. From that point forward Joan became one of his devotees, and incorporated many of his teachings into her art.

Brown's imagery took on a new turn, and her canvases began to fill with animal images; one was the tiger, her Chinese astrological symbol. Esoteric signs and symbols replaced the domestic situations of the previous decade. The paintings and public artworks that Brown created in the final phase of her life were stocked with a bestiary of birds, cats, dogs and fish as well as hybrid creatures that illustrated Brown's personal belief that the Age of Aquarius was indeed dawning. One assignment she often gave her undergraduate painting students was to paint themselves in the form of animals.

"One of my main interests is archeology and anthropology," she told Zan Dubin in 1986, "and in the last 10 years I've traveled to archeological sites in Egypt, India, South and Central America and the Orient. In the art I saw, the thread running through all the ancient cultures is the symbolism of a golden age -- whether represented by the yin and yang or by men and women shown as the sun and moon." Brown's New Age convictions, and her continuing insistence on doing things her way, gave her images a cryptic quality. "Brown," states journalist Abby Wasserman, "after all is said and done, has written in a code known only to her."

Critics often gave Brown a tough time. In a 1986 review of Brown's exhibition "From the Heart," Colin Gardner of the LA Times called Brown out for her "self-righteous body of work," and didn't stop there. "This art is so absorbed in its own blinkered ego that it makes the need for critical response totally irrelevant," he wrote. Of course, Gardner wrote that just before the similarly self-righteous qualities of Frida Kahlo's paintings began to draw critical attention and public adoration.

After her heart-opening introduction to Sai Baba in 1980, Brown tried to create works that expressed her new ideals of service and compassion. In the 80's Brown's public works began to appear in "democratic" spaces including parks, plazas and shopping malls. Her 36 foot tall "Horton Plaza Obelisk," dedicated in 1985, is divided into three sections -- the earth, sea and sky -- and features images of a jaguar, fish, the sun and the moon. In a lecture given to a San Diego Sai Baba group coinciding with the monument's dedication, Brown stated that her art was an expression of "...the superconcious, which is a very spiritual way of being."

In the Fall of 1990 Joan was in India completing the project of a lifetime, an obelisk meant to celebrate Sai Baba's sixty-fifth birthday. In a freak accident, a concrete turret of the new museum where the installation was taking place collapsed, instantly killing Brown and two assistants who had traveled to India with her. By the time of her death at the age of 52, Joan's dark childhood had faded into a distant memory. Six months before, she had written to Sai Baba, who she now considered to be both her spiritual mother and father in one being:

"Words cannot express the great joy and gratitude that I feel within my heart."

It hadn't been an easy journey, but the years of painting the journey her own life as a visual diary had turned Joan Brown inside out, opening her up to unexpected joy.

October 14, 2011 through March 11, 2012

The San Jose Museum of Art

The San Jose Museum of Art