"Well, crazy wisdom--that's a very good question--is when you have a complete exchange with the road, so that the shape of the road becomes your pattern as well. There's no hesitation at all."It has been almost exactly thirteen years since Eric Orr, the Kentucky born Light and Space artist, died of a heart attack, just short of his sixtieth birthday. He would be pleased to know that his wife, Peggy Tilbury Orr, and his daughter and son, Elizabeth and John, are all thriving. Orr would also be proud to know that both of his adult children have recently become very active in preserving his artistic legacy.

-Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Elizabeth Orr is an artist and video editor. She is also, most recently, a lighting and sound designer who has been re-lighting the European revival of a Guy de Cointet play that her father did the lighting and stage design for 30 years ago. In fact, Elizabeth's parents met during the production of the play.

John Speed Orr has matured into a gifted ballet soloist; "He looks just like his father, but without the beard," Peggy says. In January of 2012 Eric Orr's 1968 sculpture and performance "Wall Shadow" will be restaged in Los Angeles as part of Pacific Standard Time, in a collaboration between LAND (Los Angeles Nomadic Division) and Corazon del Sol. John Speed Orr will be building and then removing the cinderblock wall used in the piece, just as his father once did.

Elizabeth, who was very close to her father has spent the past 5 years piecing together a forty minute film about him. She was fourteen when he died -- the same age that Eric was when his father died -- and the film project has been her way of re-connecting and of remembering. "Just hearing stories about him and how much of an impact he had on his friends lives was really amazing," Elizabeth says. "It fills in my memory of him and what he was doing with his work when I was a kid."

The film is called "Crazy Wisdom," in honor of the kind of holy madness that Orr admired in Buddhist thought, and that he lived every moment of his life. Peggy Orr says that her husband was "a showman, a personality, a genius..." His friends, interviewed by Elizabeth for her film, concur, and have a few more comments on top of that.

He was "an outlaw," says Kent Hodgetts, "a raconteur," says Larry Bell, "terrifically literate," says Maurice Tuchman. Susan Kaiser Vogel remembers his "unconditional friendship," and that he provided "adventures in the crazy zone." Orr was, in fact, California's version of Yves Klein, a metaphysical adventurer who was unafraid of limits and who saw potential where others saw impediments and voids.

"Stop moving," Orr once exhorted, "and see the electric man inside."

Twenty-five years ago I briefly visited Orr in his Venice studio after purchasing one of his paintings, a deep emerald field framed in lead and gold. I don't remember what we talked about, but as I was leaving he handed me a small black book that has sat unopened in my bookshelf until now. A catalog for a twenty year survey of his work held at San Diego State in 1984, it includes a biographical timeline peppered by short, vivid entries that hint at Orr's sense of counter-cultural adventure.

"My father was a horse breeder and trainer, " Orr told Kristine McKenna of the LA Times in 1996. "My mother was a former flapper, and I had a privileged upbringing that ended with the death of my father and the disappearance of the family fortune when I was 14." After a few years in a military school, Orr was feeling curious, rebellious, and ready to take on the world.

As his timeline tells the story he had a "first brush with death" in Mexico City at age sixteen, traveled to Cuba at eighteen, and hitch-hiked to the East Coast at nineteen, where he had an encounter with artist Marcel Duchamp's famous "Large Glass." Reading what happened next -- peyote experiments with friends, the founding of a motorcycle club, agitating for civil rights in Mississippi -- establishes Orr's connection to idealistic ferment and experimentation of the early 60's.

His first exhibited artwork, "Colt 45," consisted of a chair set in front of a box containing a .45 automatic pistol, which had its trigger attached to a foot-pedal. The gun was aimed directly at the chair. "Seated there," wrote Eric's great friend and advocate, Thomas McEvilley, "one gazed down the muzzle of a gun about 3 feet away." Of course, the gun wasn't loaded, but Orr's piece -- made years before Chris Burden created similar works dealing with bodily harm and imminent fear -- announced that Orr "was against painting and sculpture and what they stand for."

"I'm interested in the stuff you don't see but its there," he told McEvilley.

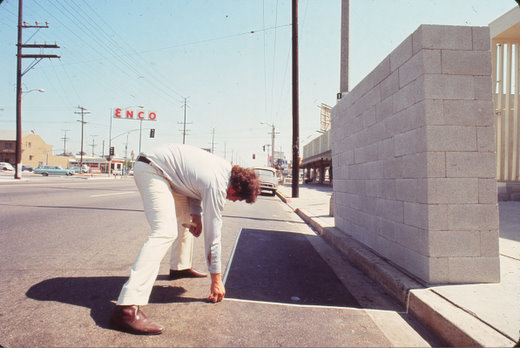

Orr moved to Los Angeles in 1965 to work for sculptor Mark di Suvero, after "terminating his formal education." He had attended 5 universities without ever finishing a degree. In 1968 he participated in experiments in hypnosis and passed out 10,000 bags of fresh air in downtown Los Angeles. He made dry ice sculptures with Judy Chicago and Lloyd Hamrol, and also created a seminal work called "Wall Shadow."

For "Wall Shadow," Orr built a 7 foot wide wall of cinderblocks and then traced and painted in its afternoon shadow on the asphalt of La Cienega Boulevard. He then removed the bricks and left only the painted shadow behind. Until the very end of his life, Orr would continue to create challenging works that fused performance and sculpture.

After spending 2 years making a "Sound Tunnel" and the first version of his "Zero Mass" installation, Orr sold everything he owned and took a trip around the world, visiting Burma, Japan, Egypt, and India, seeking sacred sites. In the years that followed, one of Orr's artistic preoccupations was the creation of sacred spaces and experiences in a contemporary context.

Upon his return to California he Orr was immediately busy, making sub-atomic drawings and solar fountains. He also conducted what he called "Out of Body" experiments. Orr's interest in sound eventually culminated in a 1981 museum installation called "Silence and the Ion Wind," in which he attempted to create "profound silence."

Although he was most often linked by critics to the California "Light and Space" Movement, which had its artistic roots in Minimalism, Orr's many interests and experiments continued to make his work hard to label. Orr's fascination with the intangible didn't help. As he once expressed it: "The most widely held misconception about Light and Space art is that it involves things; in its purest form, it's completely intangible and exists only in the sensate mind."

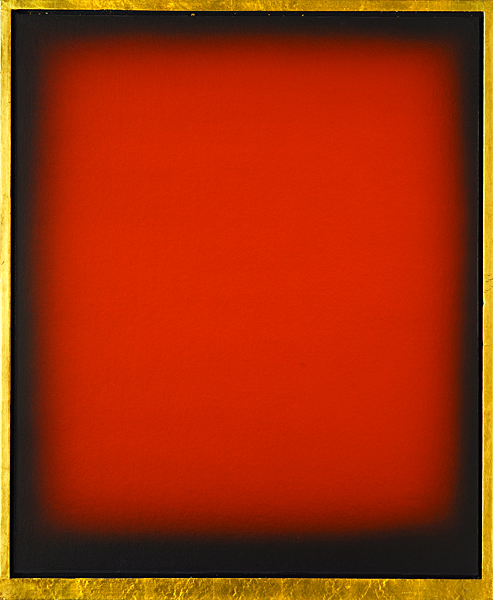

Despite his earlier rejection of the art of paintings, by the early 1980s Orr was selling quite a few of them. He now had a family to support; he and Peggy married in 1982, and Elizabeth arrived in 1984, a year after Eric purchased health insurance for the first time in his life. Orr's paintings -- enticing voids and floating gem-hued color fields -- were often compared with Mark Rothko's paintings, but there were some key differences. Rothko's ragged fields of paint float somberly, suggesting atmosphere, while Orr's paintings seem serenely empty. "I make a work as simple as the concept of zero," is how he put it.

Eric Orr, Marin Red Void, 1996, oil on canvas with gold leaf wrapped wood, 29 x 24 inches

Orr's paintings were framed in lead-wrapped gilded edges, and had touches of the artist's own blood discretely applied to each canvas. Each week, recalls art dealer Mark Moore, a doctor came to draw some of Eric's blood which he kept vials in the refrigerator along with champagne and Häagen-Dazs bars. "Many of his works now have mold where the blood was applied," Moore notes; "It is, after all, an organic substance." Blood wasn't Orr's only unusual ingredient. He was also known to incorporate crushed AM/FM radio parts and bits of human skull in some works.

Moore also remembers how hard driving and hard working Orr was. "He lived as big as he could, and when the money came in he would get a bigger place. Every time I sold a piece he had me FedEx him the check the same day."

Part of the artist's constant need for money was related to his water sculptures. Inspired by cultic sites he had visited and studied in Egypt and Zaire, Orr had developed horizontally ridged water sculptures that featured sheer streams of water clinging to their surface as it flowed downwards. In 1981 he exhibited a 20' tall example at the LA County Museum of Art. Water sculptures -- he did not think of them as fountains -- became one of Orr's signature products, and their fabrication was expensive and time consuming.

As his children grew up, they were mesmerized by their father's energy and activities. "He was really fun, and also very hardworking," Elizabeth remembers. "He would listen to the Oldies station all the time while he was working in his studio, gold leafing, airbrushing paintings etc. In the Venice studio there was always a long table in the studio with great wood chairs for friends to sit around in. I remember loving going to sleep when there were tons of people in the other room, talking, smoking, drinking and laughing; so comforting. "

Orr wasn't just interested in art. "Eric was obsessed with cars," Peggy Orr recalls, "and he couldn't wait until the new issue of Auto Trader came out. He would read it, smoking Tarrington filters. He bought a Porsche, a Cadillac convertible, a 1963 Thunderbird, and Buick Skylark from the 60s..." Elizabeth remembers "...lots of speeding on the PCH in some great car he would buy; my mother and father were both great at talking themselves out of tickets. My brother John Speed and my dad were big into Jr. Dragster racing; my brother's car was named Godspeed."

One of the "crazy wisdom" qualities that Eric demonstrated to both his children was fearlessness. "We were once watching the Blue Angels on the San Francisco Bay, and he suggested we just simply walk onto a high security military ship with all the decorated high ranking officials to watch the Blue Angels," Elizabeth recalls. " We did."

As he became an international figure -- Orr took part in the 1988 Olympic Arts Festival in Korea -- major commissions were coming his way. In 1991 he completed twin 35' tall bronze towers, to be situated in front of a 55 story office complex at the northwest corner of Wilshire and Figueroa in Los Angeles. Titled "Prime Matter," the sculpture has a remarkable feature: fire, which normally shoots upwards, moves down the towers alongside clinging sheets of water. "When that fire goes on the traffic stops at a green light," Orr boasted. At night, a xenon lamp shoots light upwards 1,000 feet, adding to the spectacle.

A 1996 piece, "Fire Window," installed in Viaduct Harbor in Auckland, New Zealand, combines gas jets and flowing water. As hidden gas jets in a cast-iron window frame create an invisible "pane" of heat, water flows over it. To suggest the "unpredictable forces of nature," the gas jets periodically burst into flame.

Orr's final major commission, "The Electrum Project," completed the year before death, used a new medium: giant bolts of electricity. Working with Greg Lehy, an electrical engineer, he constructed the world's largest Tesla coil -- rated at 130,000 watts -- on the farm of a private patron in New Zealand. Conceived as a sculpture/performance object, after "Electrum's" completion Orr sat on a plastic chair and read inside the coil while it was discharging, a mesmerizing stunt. "He read Plato in the chair," recalls Peggy Orr, "He did Tesla one better."

Sophie Chahinian, who managed Orr's studio on Abbot Kinney Boulevard, remembers that the summer before Eric's death he was feeling "nostalgic," and working on a series of short recollections that he called "Ghost Stories." Some were about his friends, some about his boyhood in Kentucky and all of them were quite short.

Much of Orr's time was now spent on water sculptures, which had become his most important studio products. "The simple elegance of his water sculptures made them majestic and subtle at the same time," says Chahinian. "His proposals were original and organic and he was so amazingly smart. He had such a good sense of humor, with a sardonic edge, an affinity for that which was reduced to absurdity, a fatalism that was his undoing. He should have quit smoking two packs a day a long time ago, but that wasn't something he was going to entertain."

Orr died in November of 1998, just after returning from a trip to Las Vegas, where he had presented a proposal for a water sculpture for a major hotel. Members of his studio team, including Sophie Chaninian, Tudor Farmer, and others, completed a final commission -- which features undulating panels of water flowing over copper in the atrium at Center of Science and Industry in Columbus, Ohio -- after his death.

"He was such a great spirit," Elizabeth Orr says. "His work is really powerful, timeless... His installations, performances, and objects are so present even now and you've probably seen his works in major museums, and in his public installations without even realizing it." In particular, Orr's water sculptures -- and fountains derived from his ideas, which he never managed to patent -- seem to be everywhere. They can be found in corporate lobbies, public plazas and even department stores where small "Zen" fountains mass produced in Asia are derived from Orr's water sculptures.

By his death in 1998, Eric Orr had fearlessly taken his experiential art in an astonishing range of directions, while at the same time remaining interested in essential experiences and elements. He might have been surprised to find that his work has had a kind of reincarnation through the efforts of his children. " I also relate to early Buddhism in that I have no sense of the afterlife, he once told an interviewer. "I think we're like television sets, and when we die, the off button is pushed and the show is over."