If you were to tell the New Zealand born artist Matthew Couper that he is living in the wrong era -- and possibly the wrong city -- he would just smile. He is more than comfortable being anachronistic.

Couper, who specializes in making contemporary paintings that have their stylistic roots in Spanish Baroque colonial art, says that he is "... OK with being part of a tradition." Add to that, working and living in Las Vegas, a city known for theatricality, luxury and its tolerance of sin, suits Couper beautifully. His style may be 300 years old, but his art needs social extremes to activate its sense of morality, and he sees potential in the city. "Las Vegas is a one in a million place," Couper comments, "and there is no parochial sense of what art is."

Matthew Couper with the sarcophagus of Fra Angelico in Rome, Photo: Jo Russ

Being a recent immigrant to the U.S. has also contributed to the complex, hybrid nature of Couper's imagery. "I'm starting from scratch," he notes, "but knowing that I need to assimilate socially and culturally but while retaining a sense of where I came from." Couper came to Las Vegas -- by choice -- in mid-2010, and although many of his themes are universal, he knew that Vegas would give him something he could "tap into."

An artist with a Kafkaesque view of the world, Couper uses his art to narrate personal uncertainties, and frustrations. He has found more than enough strangeness in Vegas -- and in America -- to challenge and stimulate his secular piety. Couper is both an intuitive, a moralist and a visionary. His recent oil "Trickle-Down Theory," which features the Las Vegas Stratosphere tower pissing out a golden stream of urine over a Boschian cast of characters, makes a dark pun on conservative economic theory, and somehow manages to do so with religious conviction. The resulting image is compelling, perplex and idiosyncratic; a Pagan Catholic Cirque du Soleil.

Matthew Couper, "Trickle Down Theory," 2011, Oil on canvas, 58" x 46"

Couper grew up in a religious household, but not a visually devout one. He recalls that religion was "kind of there... but no dripping Spanish crucifixes." Still, at age 4 he drew his first crucifix: he had seen one at his grandparent's house

As an art student, when Couper first came across an ex-voto painting -- a small blue painting on rippled tin -- he felt an immediate pull. "That small image of a Mexican woman kneeling before a vision of the Virgin of Guadalupe held it's own on the wall," says Couper; "It pinged!" As he intuitively realized, Spanish colonial art, with its saints, monsters, and acts of devotion, represents a very powerful moment in culture; the moment when a pagan society collided with orthodoxy.

Couper soon started collecting both retablos -- paintings dedicated to a particular saint -- and ex-votos, which describe personal experiences and offer thanks. They have given him a narrative vocabulary, and he also admires their humility. "I think I like them because there's no cult-of-personality tied up with these works," Couper comments. " In fact the artists were really artisans just doing 'God's' work. No politics, no egos, what a great way to earn a wage!"

Ex-votos and retablos, with their stark symbolism, were painting to be instantly understood by largely illiterate populations. Couper, on the other hand, is painting for a population that has been overstimulated by too much information and too much entertainment. By appealing to our neglected religious imaginations, Couper has paradoxically managed to make images that stand out as literally unorthodox.

Couper likes what happens when an ancient symbol is brought into a contemporary context. In "Trickle Down Theory" a snake with the dollar bill's Great Seal on it's back stands for the shrewdness and astuteness of art collectors. In "21st Century Caravaggisti, Las Vegas, NV" a painting monkey "multi-tasks" at a strip club, evoking Couper's sense of the "work hard/play hard" American blue collar workers that frequent Vegas casinos.

His symbols, which can seem jarring in a contemporary context, may strike some as Surrealist, but that isn't quite right: they are Pre-Surrealist -- in fact they are Pre-Englightenment -- and don't need to be seen as having Freudian meanings. Couper puts it this way: "I do like Surrealist artists such as de Chirico and Magritte, but I see them as part of a long lineage of painters going back to the image-makers in the Lascaux Caves." Couper's symbols aren't self-conscious or over-thought; they are an acquired vocabulary that his imaginative mind uses nimbly.

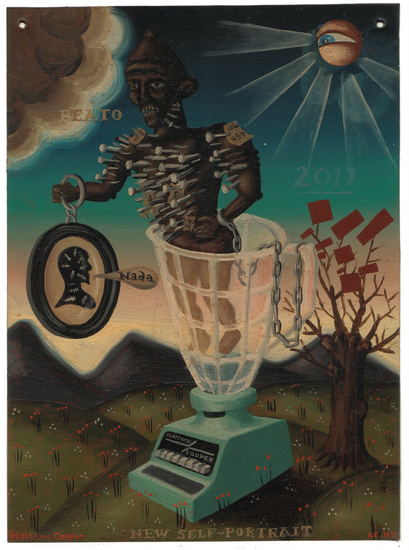

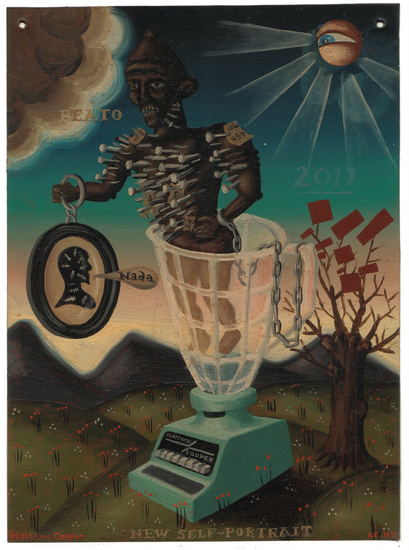

Matthew Couper, "New Self-Portrait," 2011, oil on metal, 11" x 8"

Interested in what happens when cultures merge and hybridize, Couper doesn't hesitate to combine eclectic cultural products. In a recent self-portrait, an African power figure stands in a blender, holding the scarred silhouette of the artist in an uncertain symbolic relationship. Behind the figure a tree sprouts red planar leaves that recall the Suprematist paintings of Kasmir Malevich. "The Nkisi Nkondi power figures interest me because of their devotional significance," Couper comments, "but I still haven't entirely worked out what this painting means."

Couper's ideas, whether they appear to him in the shower, or in a dream, come from simple personal experiences, but take on a new life when expressed by his anachronistic and esoteric symbols. In a 2009 retablo, for example, Couper conjured up a robed Friar gnawing a human leg to express how he felt about a 15 hour per week job teaching art at Wellington High School. A red inscription -- "A man's gotta EAT!" -- provides a rationalization for this instance of Catholic cannibalism.

Darkly funny, and dense with symbols, Couper's paintings are his attempt to bridge the gap between the mundane and the spiritual. It isn't an easy job, but Couper has a powerful set of artistic traditions to draw on when he gets stuck. Couper is, in fact, one of the more humble and sincere contemporary artists working today. He is a storyteller on a pilgrimage, recording his experiences in a visual language that once spoke power to people kneeling in a church.

His best paintings shatter our cultural narcissism and remind us of what ancient peoples once knew: our fate is determined by Saints and monsters.

Couper, who specializes in making contemporary paintings that have their stylistic roots in Spanish Baroque colonial art, says that he is "... OK with being part of a tradition." Add to that, working and living in Las Vegas, a city known for theatricality, luxury and its tolerance of sin, suits Couper beautifully. His style may be 300 years old, but his art needs social extremes to activate its sense of morality, and he sees potential in the city. "Las Vegas is a one in a million place," Couper comments, "and there is no parochial sense of what art is."

Being a recent immigrant to the U.S. has also contributed to the complex, hybrid nature of Couper's imagery. "I'm starting from scratch," he notes, "but knowing that I need to assimilate socially and culturally but while retaining a sense of where I came from." Couper came to Las Vegas -- by choice -- in mid-2010, and although many of his themes are universal, he knew that Vegas would give him something he could "tap into."

An artist with a Kafkaesque view of the world, Couper uses his art to narrate personal uncertainties, and frustrations. He has found more than enough strangeness in Vegas -- and in America -- to challenge and stimulate his secular piety. Couper is both an intuitive, a moralist and a visionary. His recent oil "Trickle-Down Theory," which features the Las Vegas Stratosphere tower pissing out a golden stream of urine over a Boschian cast of characters, makes a dark pun on conservative economic theory, and somehow manages to do so with religious conviction. The resulting image is compelling, perplex and idiosyncratic; a Pagan Catholic Cirque du Soleil.

Couper grew up in a religious household, but not a visually devout one. He recalls that religion was "kind of there... but no dripping Spanish crucifixes." Still, at age 4 he drew his first crucifix: he had seen one at his grandparent's house

As an art student, when Couper first came across an ex-voto painting -- a small blue painting on rippled tin -- he felt an immediate pull. "That small image of a Mexican woman kneeling before a vision of the Virgin of Guadalupe held it's own on the wall," says Couper; "It pinged!" As he intuitively realized, Spanish colonial art, with its saints, monsters, and acts of devotion, represents a very powerful moment in culture; the moment when a pagan society collided with orthodoxy.

Couper soon started collecting both retablos -- paintings dedicated to a particular saint -- and ex-votos, which describe personal experiences and offer thanks. They have given him a narrative vocabulary, and he also admires their humility. "I think I like them because there's no cult-of-personality tied up with these works," Couper comments. " In fact the artists were really artisans just doing 'God's' work. No politics, no egos, what a great way to earn a wage!"

Ex-votos and retablos, with their stark symbolism, were painting to be instantly understood by largely illiterate populations. Couper, on the other hand, is painting for a population that has been overstimulated by too much information and too much entertainment. By appealing to our neglected religious imaginations, Couper has paradoxically managed to make images that stand out as literally unorthodox.

Couper likes what happens when an ancient symbol is brought into a contemporary context. In "Trickle Down Theory" a snake with the dollar bill's Great Seal on it's back stands for the shrewdness and astuteness of art collectors. In "21st Century Caravaggisti, Las Vegas, NV" a painting monkey "multi-tasks" at a strip club, evoking Couper's sense of the "work hard/play hard" American blue collar workers that frequent Vegas casinos.

His symbols, which can seem jarring in a contemporary context, may strike some as Surrealist, but that isn't quite right: they are Pre-Surrealist -- in fact they are Pre-Englightenment -- and don't need to be seen as having Freudian meanings. Couper puts it this way: "I do like Surrealist artists such as de Chirico and Magritte, but I see them as part of a long lineage of painters going back to the image-makers in the Lascaux Caves." Couper's symbols aren't self-conscious or over-thought; they are an acquired vocabulary that his imaginative mind uses nimbly.

Interested in what happens when cultures merge and hybridize, Couper doesn't hesitate to combine eclectic cultural products. In a recent self-portrait, an African power figure stands in a blender, holding the scarred silhouette of the artist in an uncertain symbolic relationship. Behind the figure a tree sprouts red planar leaves that recall the Suprematist paintings of Kasmir Malevich. "The Nkisi Nkondi power figures interest me because of their devotional significance," Couper comments, "but I still haven't entirely worked out what this painting means."

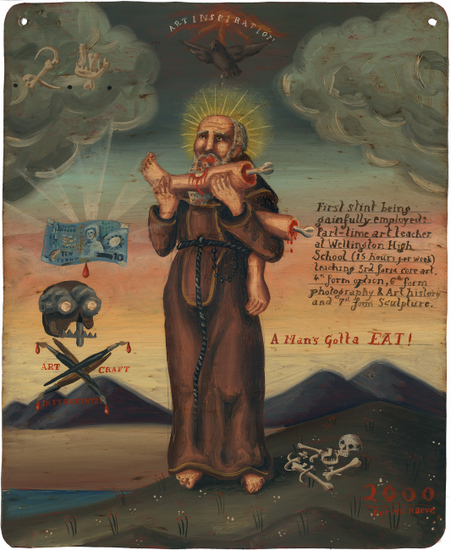

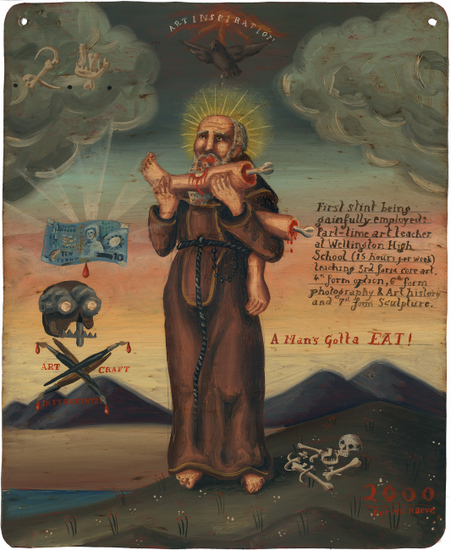

Matthew Couper, "2000 (retablo)," 2009, oil on metal, 14" x 11," image courtesy of www.paulnache.com

Couper's ideas, whether they appear to him in the shower, or in a dream, come from simple personal experiences, but take on a new life when expressed by his anachronistic and esoteric symbols. In a 2009 retablo, for example, Couper conjured up a robed Friar gnawing a human leg to express how he felt about a 15 hour per week job teaching art at Wellington High School. A red inscription -- "A man's gotta EAT!" -- provides a rationalization for this instance of Catholic cannibalism.

Darkly funny, and dense with symbols, Couper's paintings are his attempt to bridge the gap between the mundane and the spiritual. It isn't an easy job, but Couper has a powerful set of artistic traditions to draw on when he gets stuck. Couper is, in fact, one of the more humble and sincere contemporary artists working today. He is a storyteller on a pilgrimage, recording his experiences in a visual language that once spoke power to people kneeling in a church.

His best paintings shatter our cultural narcissism and remind us of what ancient peoples once knew: our fate is determined by Saints and monsters.