After artist Kyle Staver lost her older brother 6 years ago, she was moved to honor and memorialize him in the language that suits her best: the language of painting. The resulting trio of canvasses, a "Biker Triptych" now on view at the Pennsylvania College of Art as part of "Kyle Staver: A Survey of Paintings and Prints," manage to be forthright, funny, and affectionate. "To make a painting without excess irony or strategic cynicism is very edgy and I think courageous," remarks the artist. Staver, who strives to create images that balance human warmth and frailty, paints while respecting the courageous idea that "...the bravest thing in the world is to take a position without a pre-planned fall back."

Staver, who grew up in Northern Minnesota, believes that she was born strongly predisposed to art, but it took her some time, and some help from a few mentors, to find her way. While attending a girl's boarding high school as a teenager, a history teacher took her aside and told her "I know what is wrong with you; you are an artist." A few years later Staver enrolled at Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) and found that her teacher had been right. Artists were her "tribe" and the art world was her nation.

Studying with Iranian/American artist Siah Armajani, Staver developed site specific sculptures and initially had no interest in painting. That changed after graduation when, after losing her studio, a friend brought her a set of watercolors. The explosion of creativity that followed was a revelation. I couldn't believe what painting could do," is how Staver puts it. "I had no idea! I went through something like $700 worth of watercolors," Staver recalls." I made very thick impasto watercolors that first time out."

When she entered Yale for graduate work, Staver found a mentor in the late painter and critic Andrew Forge. Initially, Staver painted landscapes, but when Forge found them "lonely" she borrowed the figure of Olympia from Cezanne's painting and inserted her. "She seems a bit fearful," was Forge's comment. From that point forward Staver's engagement with the human figure became central to her practice.

In the 2 decades following her 1987 graduation from Yale, Staver gradually established herself as a painter of intimate vignettes of human relationships presented in a quirky, personal and playful style. She developed the conviction that painting had become her own non-verbal form of language capable of expressing what words cannot. Staver likes what Picasso had to say about this: "As far as I am concerned, a painting speaks for itself. What is the use of giving explanations, when all is said and done? A painter has only one language."

Honored by the National Academy Museum of New York with its "Benjamin Altman Figure Prize" in 1996 and again in 1998, Staver received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award in 2003 and began to exhibit regularly in New York.

Kyle Staver

"Cinnamon Rolls #2," 2007

Oil on linen, 54 x 64 inches

A 2003 review of Staver's work in the New York Observer notes some of the influences flavoring her work -- "... the cloistered vignettes of Vuillard... the monolithic figures of David Park, the quirky stiffness of folk art..." -- and credits her with having achieved a personal "...brand of intimism, acutely observed and gracefully set forth..." In 2006, a brief New York Times column highlighted Staver's "...playful, lushly painted pictures of people enjoying holiday or domestic pleasures."

As early as 2003 another strand had begun to appear in Staver's work that seemed to counter or even contradict the steady warmth of her established subject matter. Janice Nowinski, a Yale MFA classmate, characterizes it as "...psychological / Minnesota / backwoods stuff. Its more personal only in that its more psychological. More menace, more men -- it might have nothing to do with her personally -- but its something she tapped into which became a good subject." This strand would eventually include the biker triptych.

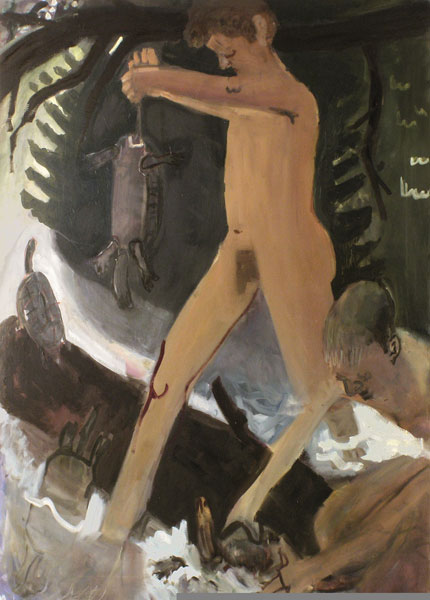

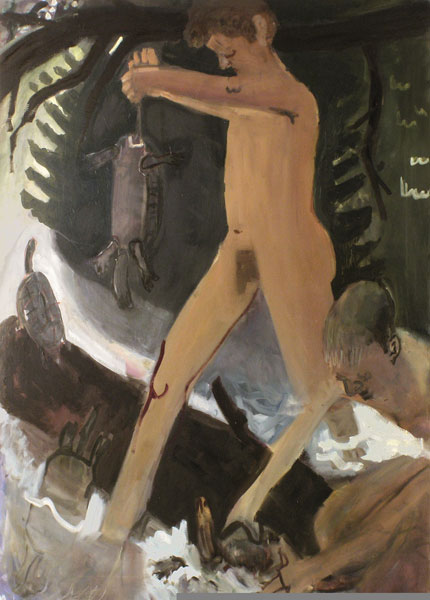

One backwoods painting, "Christmas Lake Turtle Hunt," which depicts 2 adolescent boys, is set at the sandy shoreline of a Minnesota Lake. Like several other recent paintings, "Turtle Hunt" includes male nudity, something that the artist has worked hard to depict with the right mix of humor and dignity. "In my work," she explains, "the people are naked by preference." Striving to develop nudes who were "casual and confident, humane and funny" was an ongoing artistic project. "For a man it took me years," Staver observes. "Turtle Lake" also displays the artist's increasingly confident use of stylized figures, limned with assured calligraphic details and lit with swaths and slivers of turbulent light.

Kyle Staver

"Christmas Lake Turtle Hunt," 2009

Oil on linen, 50 x 70 inches

After her brother's death Staver began the set of 3 paintings that together make up the largest sequence she has ever attempted. Each canvas has its own distinctive events and mood, but also links to the other panels; dogs appear in all 3. Because her brother had been a biker and a Harley enthusiast, Staver wanted to use the motorcycle the way Velasquez used horses in his equestrian pictures of Spanish Habsburg royalty: as the hero's mount. In each painting the artist's brother -- who was known to friends and family as "Fub"-- appears astride a motorcycle.

In the first panel, "Bad Dog on Sparta Road," Fub is embraced by a white-clad guardian angel/biker chick as he confidently zooms past a fierce dog with bared teeth. Crisp graphic rhythms -- among them handlebars and a handlebar moustache -- and a downward compositional thrust endow "Bad Dog" with dynamism and panache. It shows a man at the peak of his confidence and power, a protector who is himself protected.

Fub, leaning back with a cigarette pinched between his fingers, dominates the central panel. He is joined only by his dog Tippy, a loyal and diminutive sidekick. The motorcycle, its wheel turned forward, is delicately balanced, about to turn a corner. The bike's rear wheel sparkles like a gilded icon while Fub's firmly rendered features project saintly gravitas.

Finally, in "Dead Dog," Fub halts his bike to look over his shoulder at death in the form of a dog's broken body. A new companion, a dark haired woman, shares the view as the motorcycle's headlight illuminates the sepulchral gloom ahead of the road ahead. As in a Baroque painting, strong contrasts of light and dark suggest the dualities of life and death.

Although the paintings can be seen together as a cycle, Staver is mainly concerned that each image tells a strong story that can be related to the other panels. "What is important for me, as a painter," she relates, "is that the 3 panels hold together and have the 'gestalt' to be cohesive, without relying on pictured sequencing, as in comic books." Another element that connects the paintings is humor, something Staver finds essential; "I do think humor is terribly important in painting. It is the constant and steady reminder of our humanity; the foible aspect of being alive."

Even in working with dark material, Kyle Staver has managed to keep her sense of humor and speak from the heart. It is a vulnerable posture for a contemporary artist to take, and also a very genuine one. "I adored my brother," Staver comments, and the language of representational painting -- a language she has studied, borrowed from and personalized -- has allowed her to render that adoration in paint. "Her faith in the history of her medium may mark her (Staver) as a conservative," noted New York Times critic Roberta Smith, in a 2010 review, "but she is a very good painter."

Kyle Staver

Staver, who grew up in Northern Minnesota, believes that she was born strongly predisposed to art, but it took her some time, and some help from a few mentors, to find her way. While attending a girl's boarding high school as a teenager, a history teacher took her aside and told her "I know what is wrong with you; you are an artist." A few years later Staver enrolled at Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) and found that her teacher had been right. Artists were her "tribe" and the art world was her nation.

Studying with Iranian/American artist Siah Armajani, Staver developed site specific sculptures and initially had no interest in painting. That changed after graduation when, after losing her studio, a friend brought her a set of watercolors. The explosion of creativity that followed was a revelation. I couldn't believe what painting could do," is how Staver puts it. "I had no idea! I went through something like $700 worth of watercolors," Staver recalls." I made very thick impasto watercolors that first time out."

When she entered Yale for graduate work, Staver found a mentor in the late painter and critic Andrew Forge. Initially, Staver painted landscapes, but when Forge found them "lonely" she borrowed the figure of Olympia from Cezanne's painting and inserted her. "She seems a bit fearful," was Forge's comment. From that point forward Staver's engagement with the human figure became central to her practice.

In the 2 decades following her 1987 graduation from Yale, Staver gradually established herself as a painter of intimate vignettes of human relationships presented in a quirky, personal and playful style. She developed the conviction that painting had become her own non-verbal form of language capable of expressing what words cannot. Staver likes what Picasso had to say about this: "As far as I am concerned, a painting speaks for itself. What is the use of giving explanations, when all is said and done? A painter has only one language."

Honored by the National Academy Museum of New York with its "Benjamin Altman Figure Prize" in 1996 and again in 1998, Staver received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation award in 2003 and began to exhibit regularly in New York.

A 2003 review of Staver's work in the New York Observer notes some of the influences flavoring her work -- "... the cloistered vignettes of Vuillard... the monolithic figures of David Park, the quirky stiffness of folk art..." -- and credits her with having achieved a personal "...brand of intimism, acutely observed and gracefully set forth..." In 2006, a brief New York Times column highlighted Staver's "...playful, lushly painted pictures of people enjoying holiday or domestic pleasures."

As early as 2003 another strand had begun to appear in Staver's work that seemed to counter or even contradict the steady warmth of her established subject matter. Janice Nowinski, a Yale MFA classmate, characterizes it as "...psychological / Minnesota / backwoods stuff. Its more personal only in that its more psychological. More menace, more men -- it might have nothing to do with her personally -- but its something she tapped into which became a good subject." This strand would eventually include the biker triptych.

One backwoods painting, "Christmas Lake Turtle Hunt," which depicts 2 adolescent boys, is set at the sandy shoreline of a Minnesota Lake. Like several other recent paintings, "Turtle Hunt" includes male nudity, something that the artist has worked hard to depict with the right mix of humor and dignity. "In my work," she explains, "the people are naked by preference." Striving to develop nudes who were "casual and confident, humane and funny" was an ongoing artistic project. "For a man it took me years," Staver observes. "Turtle Lake" also displays the artist's increasingly confident use of stylized figures, limned with assured calligraphic details and lit with swaths and slivers of turbulent light.

After her brother's death Staver began the set of 3 paintings that together make up the largest sequence she has ever attempted. Each canvas has its own distinctive events and mood, but also links to the other panels; dogs appear in all 3. Because her brother had been a biker and a Harley enthusiast, Staver wanted to use the motorcycle the way Velasquez used horses in his equestrian pictures of Spanish Habsburg royalty: as the hero's mount. In each painting the artist's brother -- who was known to friends and family as "Fub"-- appears astride a motorcycle.

Bad Dog on Sparta Road, 2007

Oil on linen, 56 x 68 inches

Oil on linen, 56 x 68 inches

In the first panel, "Bad Dog on Sparta Road," Fub is embraced by a white-clad guardian angel/biker chick as he confidently zooms past a fierce dog with bared teeth. Crisp graphic rhythms -- among them handlebars and a handlebar moustache -- and a downward compositional thrust endow "Bad Dog" with dynamism and panache. It shows a man at the peak of his confidence and power, a protector who is himself protected.

Fub and Tippy, 2007

Oil on linen, 76 x 66 inches

Oil on linen, 76 x 66 inches

Fub, leaning back with a cigarette pinched between his fingers, dominates the central panel. He is joined only by his dog Tippy, a loyal and diminutive sidekick. The motorcycle, its wheel turned forward, is delicately balanced, about to turn a corner. The bike's rear wheel sparkles like a gilded icon while Fub's firmly rendered features project saintly gravitas.

Dead Dog, 2007

Oil on linen, 54 x 64 inches

Oil on linen, 54 x 64 inches

Finally, in "Dead Dog," Fub halts his bike to look over his shoulder at death in the form of a dog's broken body. A new companion, a dark haired woman, shares the view as the motorcycle's headlight illuminates the sepulchral gloom ahead of the road ahead. As in a Baroque painting, strong contrasts of light and dark suggest the dualities of life and death.

Although the paintings can be seen together as a cycle, Staver is mainly concerned that each image tells a strong story that can be related to the other panels. "What is important for me, as a painter," she relates, "is that the 3 panels hold together and have the 'gestalt' to be cohesive, without relying on pictured sequencing, as in comic books." Another element that connects the paintings is humor, something Staver finds essential; "I do think humor is terribly important in painting. It is the constant and steady reminder of our humanity; the foible aspect of being alive."

Even in working with dark material, Kyle Staver has managed to keep her sense of humor and speak from the heart. It is a vulnerable posture for a contemporary artist to take, and also a very genuine one. "I adored my brother," Staver comments, and the language of representational painting -- a language she has studied, borrowed from and personalized -- has allowed her to render that adoration in paint. "Her faith in the history of her medium may mark her (Staver) as a conservative," noted New York Times critic Roberta Smith, in a 2010 review, "but she is a very good painter."