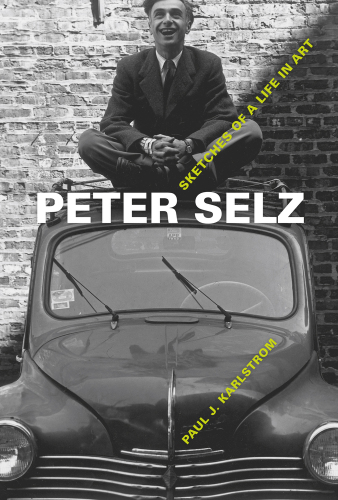

The book could have opened in Munich where Selz's art dealer grandfather introduced him to "beautiful and thrilling objects." It was this early, informal education that ultimately shaped Selz more than his official German education, which ended at age 16 when Selz was expelled from Realgymnasium for being a Jew. Since Selz's acclaimed book "Art of Engagement" opens in the Nazi death camps and then follows the thread of political art in the American ferment of the 60s and beyond, it seems reasonable to expect that the preface to his biography would open in Germany.

Then again, the summer of 1966 might have worked: Karlstrom could have described Selz and Mark Rothko meeting in Rome and driving north in a Fiat to Arezzo to see the Piero della Francesco murals in the church of San Francesco. Close friendships with artists -- including Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Sam Francis, Christo and Nathan Oliveira -- have been enormously important to Selz. When I spoke to Selz on the phone recently and asked him what he was most proud of in his career he answered without hesitation: "My friendships with artists and advocacy of artists."

Still, Karlstrom worried that opening his book with a vignette of Peter Selz hanging out with Mark Rothko or helping Sam Francis choose the title of a picture wouldn't say what really needed to be said: that the essence of Peter Selz is to be found in his individualism and his willingness to experiment and explore. "Peter is a force of nature," relates his daughter Gabrielle, "accountable only to himself."

With that in mind, Karlstrom opens his book at a restaurant in Los Angeles, where he and Selz found themselves after a long day at the College Art Association's annual conference in 1999. "The preface," notes Karlstrom, "was the only place where our personal relationship was allowed to appear." When Karlstrom suggests that Selz might want to join him after dinner at a performance art/rock concert event at Whisky a Go Go on Sunset Boulevard, Selz responds enthusiastically:

"Let's go!"

The book takes off from there, as the author and his subject walk through the door of the Whisky into a wall of highly amplified sound. "I wanted to start far away from the College Art Association annual meeting," Karlstrom says wryly. "He (Selz) is not like most of his colleagues." Norton Wisdom, a painter who assists rock and jazz musicians with putting their music into visual form -- and also a former student of Selz's -- was the featured performer that night. When asked years later, Wisdom recalled that Selz looked "at his ease, comfortable" at the event. "Selz is never out of place in any environment," writes Karlstrom." The book he has written about Peter Selz is a paean to a man who is both vastly experienced and eternally youthful in his outlook.

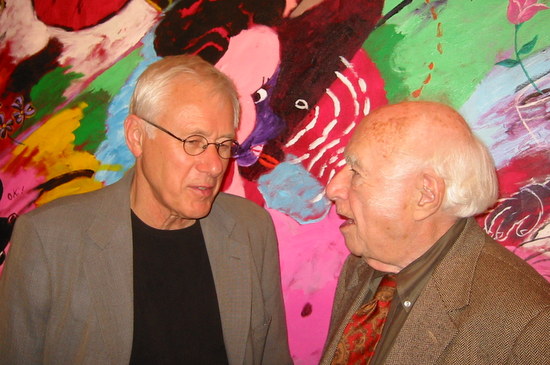

Karlstrom and Selz are friends. In fact, now that the book is finished they are closer than ever. "I got to know him very, very well," says Karlstrom, who adds that "very, very" is a Selzian way of emphasizing a key point. They first met almost 40 years ago when Karlstrom came to Northern California in 1973 to set up the first regional center of the Smithsonian Archives at San Francisco's De Young Museum. He immediately recognized that Selz, who was on his Bay Area advisory committee, was "different."

"He was supportive and he showed an interest in what I was doing," Karlstrom recalls. "Peter relates to people, and wants to get to know them. He also wants to know what people might have to offer." Although Karlstrom was at first a bit intimidated -- Selz's book "German Expressionist Painting" was the major assigned reading in Albert Elsen's modern art class at Stanford and the former undergraduate saw Selz as an icon -- friendship seemed to be almost inevitable. "It snuck up on me," laughs Karlstrom, "I realized we were friends."

"Peter Selz: Sketches of a Life in Art," was originally intended as modest collection of artist anecdotes brought together as told through interviews with Peter; at least that is what UC Press asked Karlstrom for in 2007. The book soon evolved into a full biography and the one year deadline was extended to a four year deadline. During that period, Karlstrom conducted numerous sessions with Selz -- who he had first interviewed in 1984 for the Smithsonian -- and with more than 50 of his friends, family members and associates. There were "bumps along the way" as Karlstrom dealt with some of the contradictions and complexities he discovered in Selz's personal and professional histories. For example, Selz, who has been married five times, told Karlstrom, when discussing various marital infidelities; "basically I am not monogamous."

As the book moves through Selz's dynamic postwar experiences -- as a PhD student in Chicago, an art department chair and gallery director in Pomona, and a curator of modern art at MOMA in New York -- there is a kind of collage effect as Karlstrom tries to objectively comment on the man's triumphs and trespasses. If any one pattern emerges, it seems to be that Selz simultaneously thrilled some people, while distancing others.

When Selz and his critic friend Dore Ashton proposed to use MOMA's sculpture garden as the setting for Jean Tinguely's self-destructing kinetic sculpture/contraption "Hommage to New York," his colleague Dorothy Miller scolded him: "No, our job at the museum is to preserve, not destroy works of art."

Of course "Hommage to New York" became a legend. Calvin Topkins, in his book "The Bride and the Bachelors," later described the 90 minutes of enchanting chaos that ensued as the ten dollar antique piano at the heart of Tinguely's "machine" burst into flames and destroyed itself; but not everyone was amused. Curatorial infighting, rivalry and the perception of a "glass ceiling" which kept Jews from rising to the position of museum director all colored Selz's tenure at MOMA.

By the time Selz left MOMA after seven years, "encouraged -- indeed urged" by the museum's director to take a job at UC Berkeley, Selz's vision of the art world had clarified. He had, and still has, a high regard for the tradition of the human figure in art and a dislike for the nexus cozy artist/dealer/museum connections that came on strong in the era of Pop Art. Selz has a feeling for subjectivity and metaphor, and willingness to say "yes" to new experiences and sensations. Selz also genuinely likes artists; "He literally thinks of himself as one," reports Karlstrom.

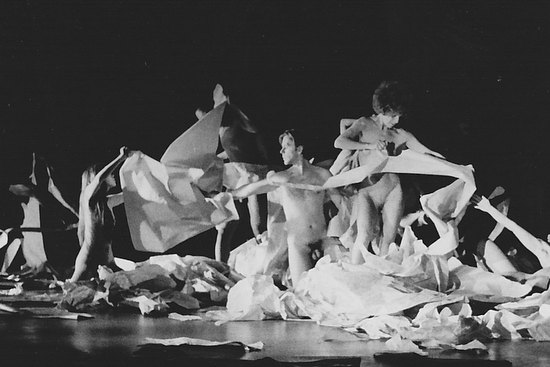

When Selz arrived at Berkeley in 1965, "as something of a star," he became both a tenured faculty member and the founding director of the University Art Museum, which was completed in 1970. He was, paradoxically, the right man for the times; a cultural authority figure who himself distrusted authority figures. Selz commissioned the avant-garde dancer Anna Halprin to create an opening performance for the new museum in which "beautiful naked young men and women flowing throughout the museum...soft flesh against hard gray concrete."

Karlstrom's book goes on to sketch many other colorful anecdotes, but he balances them with forthright accounts of some of the more mundane problems Selz the wave-maker has faced in his more than 45 years in the Berkeley community. For example, art historian James Cahill states that Selz "seldom came to faculty meetings," something Selz denies. Cahill also reports that "relations between him and most of the faculty were indeed very cool." To his students -- and Selz became a full-time professor of art history in 1972 -- Selz was often a key figure who became a mentor first, and a loyal friend over time.

"Peter Selz: Sketches of a Life in Art," is an original, idiosyncratic book about an original, idiosyncratic man. It has also been a surprise success and is on the current bestseller list of the UC Press: the first run of 2,500 hardbound copies sold out in a month. In Karlstrom's mind, it was a book begging to be written: "One of the reasons that his (Selz's) story warrants a bio is that he is truly an individual who created the place where he wanted to be." Yes, there were adjustments that had to be made along the way -- "Peter does spin" comments Karlstrom -- but Selz loves and is very proud of the completed book.

When I spoke to Selz he reminded me that his life is still a work in progress. Now 93, he is still extremely active in the art world, and is currently co-curating "The Painted Word," an exhibition which will present visual art by poets of the "San Francisco Poetry Renaissance" of the 1950s and 60s. "Then there are my 20 books," Selz notes proudly, "There wasn't time for Paul to write about those." Karlstrom gently counters that "A thorough study of Selz's books would take another volume, and that academic focus was not the goal. In fact, the main publications, including exhibition catalogues, are mentioned and described as they illuminate important themes."

Karlstrom, for his part, is happy with how the book turned out, and with the reception it has received. "Telling a life is very hard work," he says, "but I find it suits me. It allows me to indulge a keen interest in people and their stories. After all, artists -- people -- create the art, and in his way Peter is one of them." Karlstrom and his wife Ann -- who served as the book's co-author, and who calmed Selz down when the drafts in progress rattled him -- are close to Peter Selz and his wife Carole. They are always ready to come along when Selz says "Let's go!"

Who could possibly be a better guide to the "subjective, unpredictable, and contradictory world of contemporary art," through which Karlstrom says Selz has steered a "focused, if not always steady course" for more than seven decades.