Do you ever worry that there aren't any contemporary painters who have the skill of Old Masters? Have a look at the paintings of Peter Zokosky: you will likely feel reassured, and maybe just a bit weirded out. Zokosky, whose seamlessly executed and bracingly eclectic paintings have caused some to call him a "New Old Master," handles past styles and methods quite nicely. In fact, he is often asked to use his skills as teaching tools.

Ten years ago, a curator at the Getty Center in Brentwood asked Zokosky if he would be willing to create a replica of one of the museum's Rembrandt oils, "Old Man in a Military Costume." Peter knocked out a convincingly impastoed replica which he then presented next to the original at a public event while discussing Rembrandt's working methods. The replica, which Zokosky kept for himself, feels absolutely right: the old soldier's ostrich feather wavers in an implied breeze as his antique metal collar glimmers with Rembrandtian clarity.

Versatile to a fault, Zokosky has painted a portrait in the manner of Jacques Louis David in front of an audience, and in a video made for the Getty -- view it here on the Getty's youtube channel -- Zokosky's deft palette knife recreated the scabrous surface of Gustave Courbet's "Grotto of Sarrazine." Zokosky's friend, painter Jon Swihart, says he once saw a Zokosky drawing in the style of Leonardo Da Vinci "... that could have fooled even Carlo Pedretti," (the leading Leonardo expert.)

Peter Zokosky

Where did all this technical versatility and painterly confidence come from? Zokosky, who is 55, went to school during a time when most of his teachers still knelt at the altar of Abstract Expressionism. He found his direction after graduate school when he became the protégé of Richard Saar, an art restorer who taught him traditional skills and methods -- including glazing, varnishing, and water gilding -- that his previous teachers wouldn't have known how to teach him if they had cared to.

From that point forward Zokosky committed himself to representational painting, gradually moving towards greater and greater refinement. Through decades of experimentation, study, and self-teaching, he has mastered skills and techniques that most artists of his generation assume went the way of the Dodo bird. Come to think of it, the Dodo bird is something Peter might paint, if he hasn't already.

Considering his ability there isn't any doubt that if Zokosky wanted a lucrative doing society portraits - and maybe a few discreet, under the table forgeries -- he could move to Palm Beach and take it from there. The crystalline formal portrait that Zokosky executed of Bermuda's of former Premier, Alexander Scott, after a recent residency on the island, more than proves that point.

Peter Zokosky presenting his portrait of Alexander Scott, February, 2011

The problem - and what a wonderful problem it is - is that Zokosky has no interest in finding a lucrative groove. Throughout his career as an artist he has consistently followed his instincts, choosing idiosyncratic subject matter and avoiding the development of a marketable "signature style." Zokosky may have the firm hand of Rembrandt Van Rijn, but it does the bidding of an imagination that works like William Blake's. The results can be confusing, but confusion is a state that Zokosky recognizes as a state of being "open," a situation he actively seeks out.

Peter Zokosky is both tremendously earnest and genuinely curious, utterly determined to walk his own artistic path. Zokosky also embraces contradictions: he has a fascination with rational science but is equally attracted to psuedoscience and the just plain weird. His subject matter is so diverse that he has been told that his one man shows look like group shows. "Beautiful and odd, or unfamiliar, seem really important to me," Zokosky states. "I love to have opposite sensibilities coexist. Reality feels that way, and I like when paintings have that too.

Peter Zokosky, "Attraction", 2008, oil on panel, 23" x 22" framed

"Peter has a truly quirky mind, and a wonderfully wicked sense of humor," says his friend F. Scott Hess. "What other artist can you name that does food sculptures, Abe Lincoln diving for lobsters, the three graces, dead baby mummies, a portrait commission of an island president, a whole show of clowns from A to Z, Mona Lisa monkeys, and a dog doing a back flip?"

Eleana Del Rio, of Koplin Del Rio Gallery also admires Zokosky's imaginative range. "The narrative paintings of Peter Zokosky are sparked by curiosity and intuition. His paintings teem with predators and their prey, cavorting babies, and aquatic creatures enacting life and death struggles and primordial dramas. Zokosky favors subjects that instinctually appeal to him, utilizing his fascination with anatomy and marvels in the natural world."

Zokosky observes "I understand that my paintings can seem quirky. I never set out to make them that way, there not meant to be strange for the sake of being strange, they just deal with things I find fascinating and I just want to see those things exist in the outer world."

"His work," says artist Sarah Perry, "is the pinnacle of concept, mastery of material, subtlety of wisdom and absolute joy of beauty that many of us strive for. "

Peter Zokosky, "Tapir and Snake", 2008, oil on panel, 24" x 35"

In two group shows at Koplin Del Rio Gallery in Los Angeles, "Between Truth and Fiction: Pictorial Narratives," and "Self-Possessed: Examining Identity in the 21st Century." Zokosky's recent works will be giving viewers plenty to admire and puzzle over. "Between Truth and Fiction" includes Peter's "Grand Marshall," in which the artist's clown-doppelganger leads a canine Bone Parade through a barren glade.

Peter Zokosky, "Grand Marshall", 2011, oil on panel, 34" x 30"

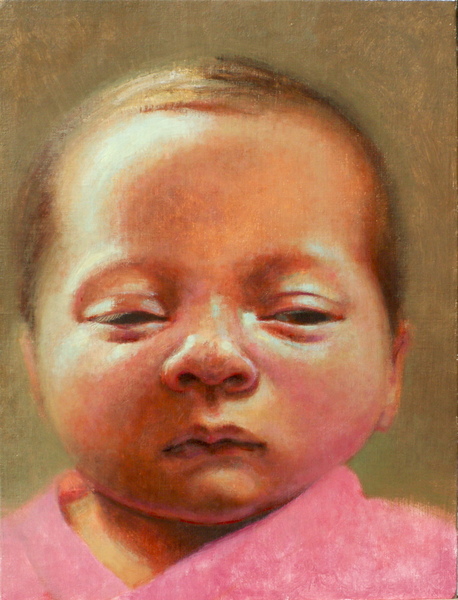

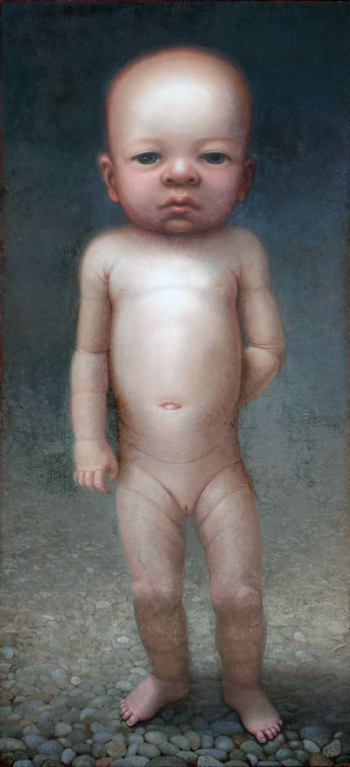

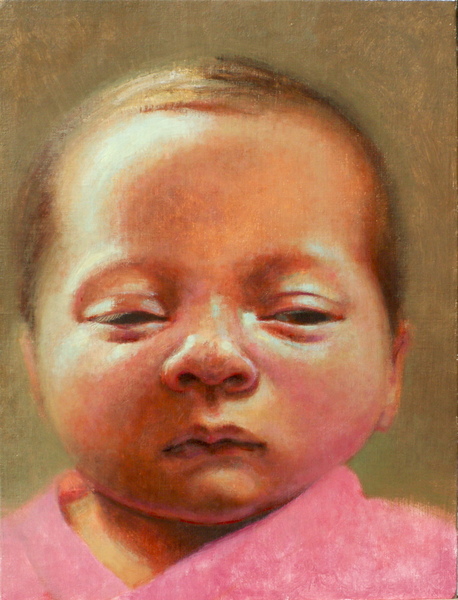

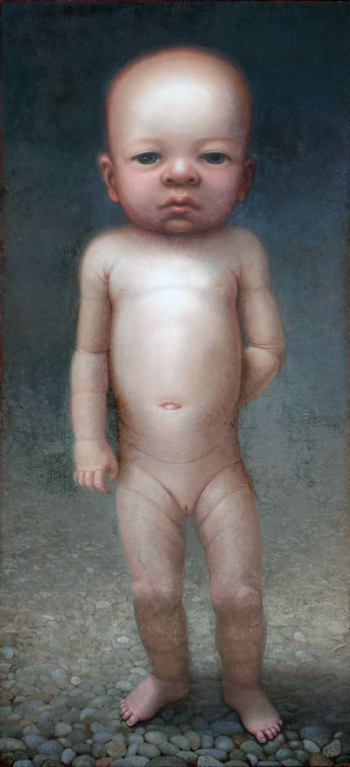

Zokosky has also been working on paintings of babies -- tiny boddhisatvas who seem to already know the world well -- that are technically stunning and engagingly subtle.

Peter Zokosky "Raina," 2012, oil on canvas, 21" x 16"

Calling Peter "a unique figure" is something of an understatement: He is a true non-conformist in a world of phony non-conformists, a painter whose best images are unaffectedly original. "Peter can take some really unworthy stupid subject," notes Scott Hess, "something other artists would never touch, and make a sublime artwork out of it." In era when curators and collectors embrace the cunning workshop productions of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons as the "norm" Zokosky's arcane, labor and skill intensive paintings look "weird," in the best possible sense of the word.

John Seed Interviews Peter Zokosky

JS: When did you know you were an artist?

PZ: It's hard to say, but I recall clearly some "insights" that might indicate an artistic, or odd, sensibility. My parents both painted and drew, both started out as artists, and both found ways to apply those interests and skills. I remember seeing their nude life drawings, and our walls had lots of their paintings on display. I loved looking at their work.

I remember being very young and awakening frightened, and going into their bedroom. Lying in bed with them I saw that the paintings had all come to life. My mother did a painting of a boy walking over stones, I saw the boy moving, rising up and down as he navigated the stream-bed, he stayed centered in the frame and the dappled light flickered over his body. My Dad had a scratchboard drawing of a New Guinea man with a pierced nose, I saw him grimace and scowl.

Another watercolor of an Indian brave on horseback seemed to move forward at a full gallop, then the Indian threw the spear he was carrying. That scared me. I also remember pondering the permanence of objects, I had a childhood theory that things disappeared when I wasn't looking at them, I would open my eyes suddenly, or turn my head, in an attempt to "catch" the thing before it reappeared. I had some strong notion that the world of appearances was somehow in flux, and if I was fast enough I'd have proof.

I recall clearly seeing a dramatic, fiery red sunset and thinking "I painted that when I was old." I'm not sure how to interpret that idea, but I was certain that I had done that. I remember some synesthesic ability. I liked to drink coffee, with lots of milk and sugar. I found that if I faced the sun with my eyes shut, I could adjust the light coming through my eyelids and achieve whatever color I wanted; when I scrunched my eyes just right I could see the color of sweet, milky coffee.

If I stuck the tip of my tongue out slightly I could taste coffee. I spent a lot of time looking at a huge book of the engravings of Gustav Dore' and I'd have fantastic dreams. I don't think I had the idea of being an artist, in a career sense, but I was fascinated by perception and loved examining things in great detail.

Peter Zokosky, "Opal", 2011, oil on canvas, 72" x 36"

JS: Can you tell me something about the importance of your mentor Dick Saar?

PZ: I met Dick Saar as Alison Saar's father. A few years later I started working for him. He was fine art conservator and restorer, and I worked for him for 6 years restoring paintings and art objects. Aside from my father, Dick Saar was the closest thing to a mentor I've had. He was a wonderful man and a great friend. He taught me everything I know about restoration, he had a remarkable patience and skill, and he knew so much about painting.

Dick was a great man; he embraced life's full range. He attended the Cleveland Art Institute, fought in World War II, raised three amazing daughters, lived a full life, and had such a great outlook on life. He loved art and he knew its structure from the ground up. Working with him was always a pleasure and often a revelation. I realized that sometimes he would spend more time with a painting than the artist had. When you examine every square inch of a painting, re-adhere loose paint, fill in losses, and retouch missing sections, you get to really know a painting and appreciate good craftsmanship and see the effects of bad craftsmanship.

I don't know if Dick's temperament came first, or he developed it doing art restoration, but he was an example of a man who loved his work, took pride in doing the best possible job, he was always honest with clients, and he treated me as an equal. He passed away a few years ago, even in declining health, he was full of gratitude, patience, and love. I often think of Richard Saar as a great role model who taught me so much more than technical skills.

JS: Is it fair to say that you have strong connections to various sciences; for example anthropology?

PZ: As a practicing artist, and an "art world" participant I'm familiar with that realm, but as a casual observer of "the science world", what goes on there, seems amazing and wondrous. I know that art and science have a different purpose, and both achieve something the other can't. I have to admit a profound respect for the scientific mind and process. There was a time when the two paths intertwined more.

Leonardo Da Vinci was both a scientist and artist. George Stubbs was a serious anatomist. Henry Fox Talbot made major contributions to the science of photography. Curiosity and wonder fueled both artists and scientists. I like to keep those motivations in mind. Too often, for my taste, art ends up in the fashion and entertainment arena. I like the rigors of science and the search for wisdom.

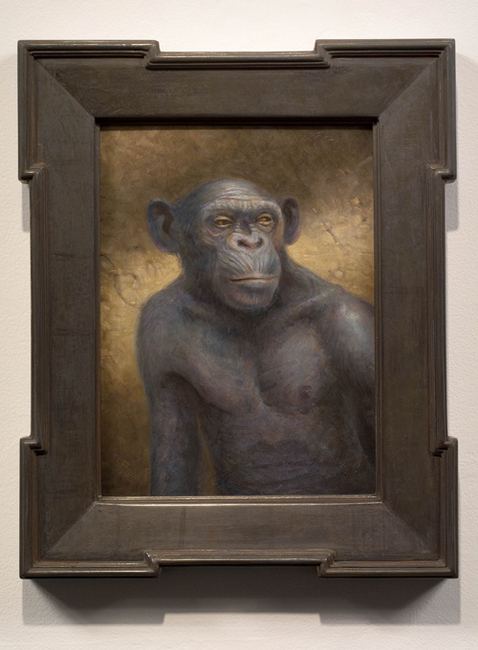

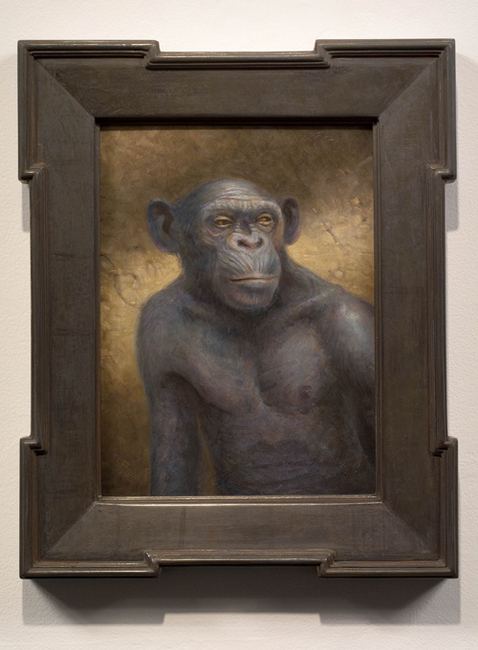

The profound creativity of someone like Paul MacCready, who made viable human powered flight, is so inspiring. I got to hear him talk and his mind was so agile and his curiosity was boundless. Primatology is another passion of mine, I've painted lots of primate portraits; I'm especially intrigued by the apes using sign language to communicate. I met some of them at Central Washington University and it was profound and humbling. Primates offer some valuable insights into our own social order and thought process.

Peter Zokosky, "Uncle", 2008, oil on panel, 16 5/8" x 13 1/2" framed

Another exciting field is neuroaesthetics, it still seems in its infancy, but it seeks to locate, measure and understand the source of the aesthetic experience. It's interesting to see that artists are, in a sense, way ahead of scientists in that field, they have been using empathy in art for centuries, and scientists have recently discovered mirror neurons. I wish there was more dialogue between the worlds of art and science, I think we could benefit each other in understanding the human condition.

JS: When people ask you about the wide and eclectic range of your subjects over the years, what do you tell them?

PZ: I understand that my exhibitions can look like group shows. I tend to wander, or, to put politely, "have a wide and eclectic range." I don't worry about that. I made an agreement with myself a long time ago to pursue whatever interests me. If each work focuses on something different, or if one subject holds my interest, I'm committed to follow through wherever it takes me.

Peter Zokosky, "El Santo", 2007, oil on panel, 31" x 25 1/2"

I recognize the commercial advantage to style, branding, and series, but I think it's a mistake to let those concerns lead you as an artist. The creative impulse is a delicate thing, if you ignore it, it goes away. My problem is I have too many things I want to make, and I know I'll never get to do them all, but I don't mind having that problem.

Never being bored or out of ideas feels right.

Under the Skin: The Art of Peter Zokosky on Vimeo.

Paintings by Peter Zokosky are included in:

Between Truth and Fiction: Pictorial Narratives

September 8 - October 19, 2012

Self-Possessed: Examining Identity in the 21st Century

October 27 - December 8, 2012

Koplin Del Rio, 6031 Washington Blvd, Culver City, CA 90232

Ten years ago, a curator at the Getty Center in Brentwood asked Zokosky if he would be willing to create a replica of one of the museum's Rembrandt oils, "Old Man in a Military Costume." Peter knocked out a convincingly impastoed replica which he then presented next to the original at a public event while discussing Rembrandt's working methods. The replica, which Zokosky kept for himself, feels absolutely right: the old soldier's ostrich feather wavers in an implied breeze as his antique metal collar glimmers with Rembrandtian clarity.

Versatile to a fault, Zokosky has painted a portrait in the manner of Jacques Louis David in front of an audience, and in a video made for the Getty -- view it here on the Getty's youtube channel -- Zokosky's deft palette knife recreated the scabrous surface of Gustave Courbet's "Grotto of Sarrazine." Zokosky's friend, painter Jon Swihart, says he once saw a Zokosky drawing in the style of Leonardo Da Vinci "... that could have fooled even Carlo Pedretti," (the leading Leonardo expert.)

From that point forward Zokosky committed himself to representational painting, gradually moving towards greater and greater refinement. Through decades of experimentation, study, and self-teaching, he has mastered skills and techniques that most artists of his generation assume went the way of the Dodo bird. Come to think of it, the Dodo bird is something Peter might paint, if he hasn't already.

Considering his ability there isn't any doubt that if Zokosky wanted a lucrative doing society portraits - and maybe a few discreet, under the table forgeries -- he could move to Palm Beach and take it from there. The crystalline formal portrait that Zokosky executed of Bermuda's of former Premier, Alexander Scott, after a recent residency on the island, more than proves that point.

Peter Zokosky is both tremendously earnest and genuinely curious, utterly determined to walk his own artistic path. Zokosky also embraces contradictions: he has a fascination with rational science but is equally attracted to psuedoscience and the just plain weird. His subject matter is so diverse that he has been told that his one man shows look like group shows. "Beautiful and odd, or unfamiliar, seem really important to me," Zokosky states. "I love to have opposite sensibilities coexist. Reality feels that way, and I like when paintings have that too.

"Peter has a truly quirky mind, and a wonderfully wicked sense of humor," says his friend F. Scott Hess. "What other artist can you name that does food sculptures, Abe Lincoln diving for lobsters, the three graces, dead baby mummies, a portrait commission of an island president, a whole show of clowns from A to Z, Mona Lisa monkeys, and a dog doing a back flip?"

Eleana Del Rio, of Koplin Del Rio Gallery also admires Zokosky's imaginative range. "The narrative paintings of Peter Zokosky are sparked by curiosity and intuition. His paintings teem with predators and their prey, cavorting babies, and aquatic creatures enacting life and death struggles and primordial dramas. Zokosky favors subjects that instinctually appeal to him, utilizing his fascination with anatomy and marvels in the natural world."

Zokosky observes "I understand that my paintings can seem quirky. I never set out to make them that way, there not meant to be strange for the sake of being strange, they just deal with things I find fascinating and I just want to see those things exist in the outer world."

"His work," says artist Sarah Perry, "is the pinnacle of concept, mastery of material, subtlety of wisdom and absolute joy of beauty that many of us strive for. "

In two group shows at Koplin Del Rio Gallery in Los Angeles, "Between Truth and Fiction: Pictorial Narratives," and "Self-Possessed: Examining Identity in the 21st Century." Zokosky's recent works will be giving viewers plenty to admire and puzzle over. "Between Truth and Fiction" includes Peter's "Grand Marshall," in which the artist's clown-doppelganger leads a canine Bone Parade through a barren glade.

Zokosky has also been working on paintings of babies -- tiny boddhisatvas who seem to already know the world well -- that are technically stunning and engagingly subtle.

John Seed Interviews Peter Zokosky

JS: When did you know you were an artist?

PZ: It's hard to say, but I recall clearly some "insights" that might indicate an artistic, or odd, sensibility. My parents both painted and drew, both started out as artists, and both found ways to apply those interests and skills. I remember seeing their nude life drawings, and our walls had lots of their paintings on display. I loved looking at their work.

I remember being very young and awakening frightened, and going into their bedroom. Lying in bed with them I saw that the paintings had all come to life. My mother did a painting of a boy walking over stones, I saw the boy moving, rising up and down as he navigated the stream-bed, he stayed centered in the frame and the dappled light flickered over his body. My Dad had a scratchboard drawing of a New Guinea man with a pierced nose, I saw him grimace and scowl.

Another watercolor of an Indian brave on horseback seemed to move forward at a full gallop, then the Indian threw the spear he was carrying. That scared me. I also remember pondering the permanence of objects, I had a childhood theory that things disappeared when I wasn't looking at them, I would open my eyes suddenly, or turn my head, in an attempt to "catch" the thing before it reappeared. I had some strong notion that the world of appearances was somehow in flux, and if I was fast enough I'd have proof.

I recall clearly seeing a dramatic, fiery red sunset and thinking "I painted that when I was old." I'm not sure how to interpret that idea, but I was certain that I had done that. I remember some synesthesic ability. I liked to drink coffee, with lots of milk and sugar. I found that if I faced the sun with my eyes shut, I could adjust the light coming through my eyelids and achieve whatever color I wanted; when I scrunched my eyes just right I could see the color of sweet, milky coffee.

If I stuck the tip of my tongue out slightly I could taste coffee. I spent a lot of time looking at a huge book of the engravings of Gustav Dore' and I'd have fantastic dreams. I don't think I had the idea of being an artist, in a career sense, but I was fascinated by perception and loved examining things in great detail.

JS: Can you tell me something about the importance of your mentor Dick Saar?

PZ: I met Dick Saar as Alison Saar's father. A few years later I started working for him. He was fine art conservator and restorer, and I worked for him for 6 years restoring paintings and art objects. Aside from my father, Dick Saar was the closest thing to a mentor I've had. He was a wonderful man and a great friend. He taught me everything I know about restoration, he had a remarkable patience and skill, and he knew so much about painting.

Dick was a great man; he embraced life's full range. He attended the Cleveland Art Institute, fought in World War II, raised three amazing daughters, lived a full life, and had such a great outlook on life. He loved art and he knew its structure from the ground up. Working with him was always a pleasure and often a revelation. I realized that sometimes he would spend more time with a painting than the artist had. When you examine every square inch of a painting, re-adhere loose paint, fill in losses, and retouch missing sections, you get to really know a painting and appreciate good craftsmanship and see the effects of bad craftsmanship.

I don't know if Dick's temperament came first, or he developed it doing art restoration, but he was an example of a man who loved his work, took pride in doing the best possible job, he was always honest with clients, and he treated me as an equal. He passed away a few years ago, even in declining health, he was full of gratitude, patience, and love. I often think of Richard Saar as a great role model who taught me so much more than technical skills.

JS: Is it fair to say that you have strong connections to various sciences; for example anthropology?

PZ: As a practicing artist, and an "art world" participant I'm familiar with that realm, but as a casual observer of "the science world", what goes on there, seems amazing and wondrous. I know that art and science have a different purpose, and both achieve something the other can't. I have to admit a profound respect for the scientific mind and process. There was a time when the two paths intertwined more.

Leonardo Da Vinci was both a scientist and artist. George Stubbs was a serious anatomist. Henry Fox Talbot made major contributions to the science of photography. Curiosity and wonder fueled both artists and scientists. I like to keep those motivations in mind. Too often, for my taste, art ends up in the fashion and entertainment arena. I like the rigors of science and the search for wisdom.

The profound creativity of someone like Paul MacCready, who made viable human powered flight, is so inspiring. I got to hear him talk and his mind was so agile and his curiosity was boundless. Primatology is another passion of mine, I've painted lots of primate portraits; I'm especially intrigued by the apes using sign language to communicate. I met some of them at Central Washington University and it was profound and humbling. Primates offer some valuable insights into our own social order and thought process.

Another exciting field is neuroaesthetics, it still seems in its infancy, but it seeks to locate, measure and understand the source of the aesthetic experience. It's interesting to see that artists are, in a sense, way ahead of scientists in that field, they have been using empathy in art for centuries, and scientists have recently discovered mirror neurons. I wish there was more dialogue between the worlds of art and science, I think we could benefit each other in understanding the human condition.

JS: When people ask you about the wide and eclectic range of your subjects over the years, what do you tell them?

PZ: I understand that my exhibitions can look like group shows. I tend to wander, or, to put politely, "have a wide and eclectic range." I don't worry about that. I made an agreement with myself a long time ago to pursue whatever interests me. If each work focuses on something different, or if one subject holds my interest, I'm committed to follow through wherever it takes me.

Never being bored or out of ideas feels right.