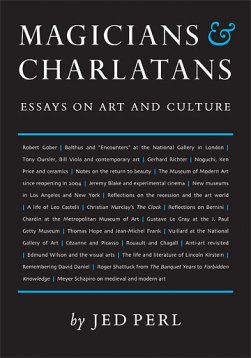

Jed Perl, who has served as the art critic for the New Republic since 1994, has a new book out: Magicians and Charlatans: Essays on Art and Culture. Published by the Eakins Press, the book is a collection of essays written between 1995 and 2011. The writings include profiles of seminal cultural figures such as Meyer Schapiro and Lincoln Kirstein, historical studies of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and Édouard Vuillard, and critical commentaries on contemporary artists Robert Gober, Gerhard Richter and Jeremy Blake.

Perl, who poet John Ashberry has called "an almost solitary and essential voice," opens the book by stating that in the past few years he has found the art world "unpredictable, fragmented, disorienting, like a hair-raising rollercoaster ride." An erudite critic who delivers his opinions unvarnished, Perl gives high praise to the 18th century master Chardin, in whose works he detects "a bold but elusive presence." He slams the contemporary German painter Gerhard Richter in whose "chilly stuff" he discerns "a loathing for painting's true magic." In his 2008 essay "Postcards from Nowhere" Perl recounts his visit to the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the LA County Museum, commenting that "BCAM is about high-end shopping" and that "you do not get the feeling that a curator has left a mark."

I recently interviewed Jed Perl to learn more about the book, his view of the art world, and about his personal approach to criticism.

John Seed Interviews Jed Perl

JS: Your book opens with a prologue titled "Laissez-Faire Aesthetics" in which you tell your readers that we are facing "a weakening of conviction, an unwillingness to take a stand." You also mention that one of your motivations for writing criticism is that you still care. In the situation that you describe, how do you keep your personal sense of caring about art and culture alive?

JP: The love of art and literature and music is very deep in us. Caring about these things is just part of being alive -- at least that's how I see it. So although I can be bummed out by a lot of what I see, the appetite is always there. Whenever I go to the galleries, whenever I go to a museum, I'm hoping I'm going to find something that satisfies this craving. And I do -- and I've written about those experiences in Magicians and Charlatans, not just the experiences with classics in the museums but also the experiences with contemporary art, like the DVDs of Jeremy Blake, about which I've written a long essay, included here. And then there's the challenge of explaining what I'm thinking and feeling; I find that challenge invigorating, even when the experiences are anything but upbeat.

JS: Clearly, you favor magicians over charlatans. Can you mention a few qualities that you feel consistently distinguish the works of the "magicians?"

JP: Magicians convince us that they've created a parallel universe -- with its own ambience and atmosphere and history and laws and legends. An artist creates an imaginative universe that is in many respects a reflection of the artist's personality and sensibility -- but also stands apart, that has a freestanding value.

JS: In your 2008 essay "Private Lives: The recession and the art world" you write that "Experience has taught me that every decade or so the art market gets weak in the knees, and when it roars back a few years later the picture palaces specializing in Warhol and other assorted idiocies are doing better than ever before." Do you see any indications that this cycle might be ready to end?

JP: Predicting the future is very difficult -- probably impossible. What has interested me in the past couple of years is the extent to which more and more people in the art world are talking about how fed up they are with our new Gilded Age. A few weeks ago, I published in The New Republic a very critical essay about Warholism and its adverse impact on the arts. I've been absolutely astonished at the depth and extent of the positive response. People I would never have dreamed of hearing from have been in touch and told me how much the essay means to them. So it seems we are at a moment when there's a lot of frustration with our market-driven art world. Where it will all lead, I can't say.

JS: Your 2002 essay on Gerhard Richter is very tough: you call him a "bullshit artist masquerading as a painter." Given that Richter is currently a market darling, have you taken heat for that statement?

JP: I've never worried about "what people think." I began writing out of a passion for art -- and out of a desire to get into prints ideas that were not in general circulation. My friends -- the people whose opinions really matter to me -- are artists and writers. I've always tried to be true to what I think -- and to more generally reflect the values and viewpoint of a community of artists and writers. I've been very lucky, in that I've found editors who support my work, often editors who are not by and large concerned with the visual arts. What has surprised me over the years, at least from time to time, is that I'll write something I think people will find absolutely outrageous -- off-the-wall -- but then it turns out that at least some people are glad I've said it. The Richter piece had that kind of impact.

Anyway, what exactly is a "market darling"? How do certain artists get that reputation? I sometimes suspect that even the people who are bidding up the prices at the auctions don't really know what they think about the work. They're just buying Warhol or Richter because their rich friends are buying it. And in some cases the main reason the museums are showing the stuff is because the trustees are major collectors. I don't think many people are really passionate about Warhol or Richter -- at least not the way artists I know are passionate about Giacometti or Morandi.

JS: "Ordinary Magic," in which you discuss the 2000 Metropolitan Chardin exhibition, comes across as one of the most heartfelt and inspired essays in your book. Is it fair to say that Chardin's ability to fuse the everyday with the extraordinary is something that few contemporary artists have managed to emulate?

JP: Different artists do different things. What Chardin did he did sublimely. But part of the glory of art is that it's as varied as human nature. And contemporary artists have their own qualities and characteristics. One of the great privileges I've had as a critic has been to write about the paintings Balthus did in his last decades when they were first exhibited. In Magicians and Charlatans I write about one of his last paintings -- a nude in a moonlit landscape -- and I do believe it's a work that adds something fresh and unique to the history art. There's always that possibility.

JS: What do you do when you aren't looking at art or writing about it?

JP: I read a great deal. Just walking around New York is something I enjoy enormously. I feel very lucky that I live in a city I find endlessly fascinating.

JS: What do you think that the situation of contemporary art -- which you indicate is driven by market forces and a desire for spectacle -- says about the times we live in?

JP: I'm a little wary about broad generalizations. Our period is a mixed bag. It's not all bad, not by any means. There are artists, writers, and curators who are doing serious work; I've written about some of what they're doing in "Magicians and Charlatans." Maybe the most important thing to remember is that we criticize because we care.