At Lora Schlesinger Gallery in Santa Monica painter/teacher/critic Lawrence Gipe is currently exhibiting thirty small paintings that simultaneously reflect both his interest in history and his ability to evoke emotion. Working from archival images that channel 20th century themes -- progress, industry, and ideology -- Gipe's subtle and somewhat abstract handling of paint adds the gleam and gloss of Romanticism. Paradoxically old and new, Lawrence Gipe's paintings have an alchemical ability to make what might be considered mundane or outdated subject matter come alive and raise new questions.

I recently interviewed Gipe and asked him about his background, his work, and his future plans.

John Seed Interviews Lawrence Gipe:

Lawrence Gipe

JS: Lawrence, can you tell me about your background, and about how you evolved into a representational artist?

LG: I went to undergraduate school in Richmond, VA at Virginia Commonwealth University (1980-84). My instructors -- many of who had been educated by Hans Hofmann in Provincetown -- taught me how to paint through abstraction. I was pushing and pulling with the best of them. The idea that color -- and juxtapositions of color alone -- could create depth, was essential to this education. It was only in my last year of graduate school at Otis (1984-6) that I decided to "convert" to imagery. Today, the lessons of Hofmann's retinal process are still behind each painting. I'm always working warm-cold, Phthalo Blue vs. Van Dyke Brown, layering transparent glazes against each other.

Lawrence Gipe, Panel No. 22 from Salon (Korea, 1950), 2012, oil on panel, 9" x 12"

My MFA studies at Otis Art Institute had a much less rigor than VCU -- there was Mike Kelley hanging around, Scott Grieger -- they were imagists as well as conceptual artists. I went to critiques at CalARTS, and, Michael Asher notwithstanding, there was a hunger for images (or at least an obsession with them), from Baldessari to Kruger. LA was an "image" city to me and I never turned back to abstraction once I hit the West Coast. A few of the instructors at Otis were swept up by the Derrida-Foucaultian revolution that was being used as critical cannon fodder at the time. I didn't see the use in much of it outside of Foucault - who I regarded highly. His identification of authoritarian structures took on a narrative power in my mind and informed my early work.

Lawrence Gipe, Panel No. 20 from Salon (Leica-Amateurs, 1937), 2012, oil on panel, 24" x 36"

JS: Nostalgia is a recurring theme in your work: how did that come about?

LG: I arrived in LA originally because my father was writing movies; he wrote a few films with Steve Martin including "Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid" -- a parody of film noir that spliced the comedian into old classics like "Double Indemnity" to make a new comedic narrative. I think a lot of my ideas surrounding the notion of "nostalgia" started to get formed then. My father -- who died at age 52 in 1986 -- lived in the past - and my primary intimacy with him was watching late-night 1930's Warner Bros. movies - which became my nostalgia as well. The highlights of his childhood became my childhood: that compression, that transparency of time and visual culture, became my own generative fiction. I'm interested in how other artists have dealt with the notion of nostalgia and have a small blog dedicated to it.

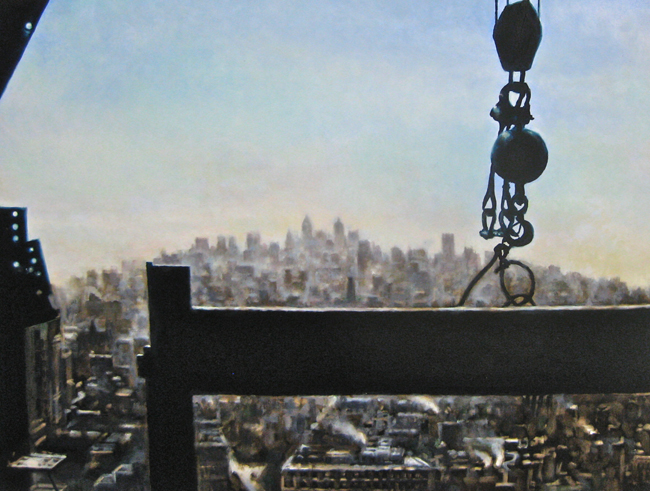

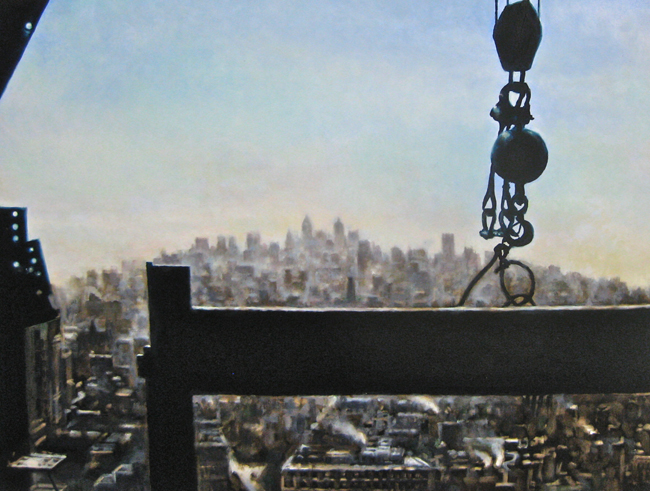

Lawrence Gipe, Panel No. 11 from Salon (New York, 1929), 2012, oil on panel, 18" x 24"

JS: Tell me about the themes of progress and industry that have been appearing in your paintings.

LG: I think my obsession with industrial images and what I call the "Cult of Progress" was inspired by my early surroundings (Baltimore) and contact with an older generation that regarded the United States as an unflawed land of opportunity. I was in a "cusp" generation: still proud of the past but anxious about the present. By the time I was growing up in the late-70's the optimism bubble had burst: gas lines, the end of the Vietnam War - it wasn't pretty! The same factories portrayed in the WPA-era, for instance, looked much less attractive in the 70's. To me, a line of towering smokestacks belching into the clouds was a very ambivalent image; it meant people were working, but it also illustrated how the filthy end of the industrial revolution was coming to roost for my generation to clean up. Industry is glorious - and horrible. I'm always attracted to themes like that.

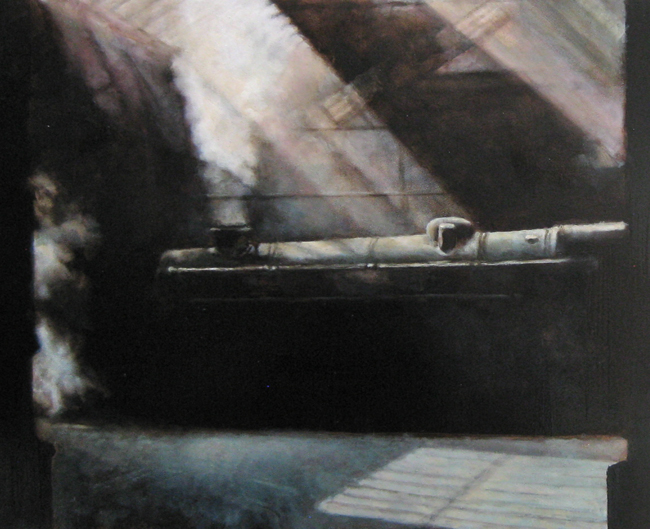

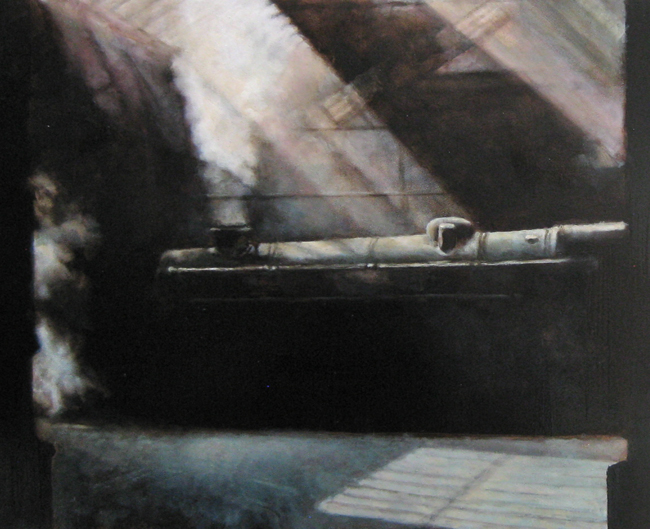

Lawrence Gipe, Panel No. 23 from Salon (Sicily, 1944), 2012, oil on panel, 11" x 44"

JS: Although you have a strong intellectual bent -- and also an interest in history -- your work also has an overlay of emotion and romanticism, right?

LG: A typical painting that straddles emotions, and a favorite image of mine from the current show, is "Sicily, 1944". Through my research, I found a book called "Flight to Everywhere", published in 1944 by Life magazine in cooperation with the War Office. Essentially, it documented a propaganda stunt: to show the public that, despite the war, the US still had dominion over the entire world. In it, a plane circumnavigated the globe, stopping in Allied air bases all along the way. Near the end of the journey, they made a stop in Sicily, which had just been secured by the US Army. That evening, the Nazis returned at night for a retaliatory raid, bombing the harbor of Palermo.

In the morning, when the photographer went out to look, he saw a golden dawn and an ominous cloud of ash hovering over the harbor. It was beautiful and tragic all at once -- so, for me, perfect. And, I think painting is the best medium to capture that couplet, as the layer of romance a painter can add complicates matters more than a photograph. It's really OK to have two different feelings about an image simultaneously. I always say, if you don't risk being misunderstood, it's not worth doing.

Lawrence Gipe, Panel No. 4 from Salon (London, 1940), 2012, oil on panel, 12" x 16"

JS: The exhibition at Schlesinger is titled "Salon," and it includes a selection works by your students. How did the show develop that way?

LG: I kind of meant for this current "Salon" exhibition to be like a "greatest hits" record - I didn't want to tuck all the work under a specific theme, like I usually do. Most of the pieces took less than a week to make, so I was able to say to myself: "paint whatever pleases you today". I was on a sabbatical from the University of Arizona and I had the time to fail and discard, without getting nervous. The two drawings in the show of the riot police were executed last summer - they took as long as ten paintings. After the buoyant, color world presented by the paintings, I wanted the viewer to be grounded back in reality by the starkness of the drawings.

In regards to the student exhibition, that was in response to an offer by my dealer, Lora Schlesinger, for me to curate the back gallery. I thought showing my current students and recent alumni would be fun. In terms of my teaching style, I don't create "acolytes" -- only one of the artists in the show deals with issues that are related to mine. I encourage abstraction in my classes, in fact, but my only interest is to find out what interests them and help them manifest that in art.

Lawrence Gipe, Panel No. 15 from Salon (Divers, 1936), 2012, oil on panel, 12" x 16"

JS: In addition to painting and teaching, you are active as a critic. Do you find that writing informs your painting, or do you try to keep criticism and studio practice separate?

LG: I love writing about art -- in the short form. I write reviews -- 250-400 words -- that's how I'm most efficient. As far as writing informing my painting, I feel like own practice is a truculent beast that isn't much affected by my journalistic ventures, especially since I tend to choose sculpture or installations to write about. More than anything, I like research. A musty stack of post- war Soviet magazines gets me really excited! I'm always attracted to what a recent lecture at the Wende Museum called "The Politics of Happiness". I'm fascinated by how artists have collaborated with and visualized totalitarianism: the perfect, monolithic worlds they portray. I think a clandestine poster collecting tour to North Korea would be my dream trip.

Lawrence Gipe, Salon No. 2, 2012, oil on panel, 20" x 29"

JS: What is next for your work?

LG: Right now, my work is going in 4-5 different directions. I realize this is detrimental to my career: I can't "brand" myself the way a lot of artists do. Yes, if you see an image of a train blasting out of a station, you can guess it's me. But, I'd just as soon paint portraits, a still life, a landscape with placid birches. All that's important is where from where the image is derived. And, with me, you can only be sure it's from a sinister context -- if those are birch trees, they're Soviet birch trees! Images like these - these kind of banal images -- are interesting to me because they seem familiar, but in fact they've come from obscure and forgotten contexts.

Lawrence Gipe, Panel No. 18 from Salon (USSR, 1962), 2012, oil on panel, 14" x 11"

I usually paint, but I also love drawing and seek out projects where it can be used autonomously and relevantly. I'm currently engaged in an on-going series about Operation Streamline, a federal policy enthusiastically endorsed by the Arizona court system that dispatches 70 illegal immigrants per day back across the border.

The series utilizes only drawing -- and that is the only means available to document the proceedings of Operation Streamline (photography is prohibited in the court). It's a sad spectacle -- they are captured and thrown into court unwashed and shackled -- they shuffle into court after being advised to waive their rights and plead guilty. Incensed by this practice, graduate students in the UA Journalism department proposed collaborating with me to sketch the deportees as they waited in the dock. An exhibition is in the works, combining video, the oral histories collected by the journalist students, and my drawings.

Lawrence Gipe Salon

Lora Schlesinger Gallery

January 12 - February 23, 2013

In the East Gallery: Emerging Artists curated by Lawrence Gipe: Nidaa Aboulhosn, Karen deClouet, Mena Ganey, Bobbi Gentry, Yubitza McCombs, Chris McGinnis

John Seed Interviews Lawrence Gipe:

LG: I went to undergraduate school in Richmond, VA at Virginia Commonwealth University (1980-84). My instructors -- many of who had been educated by Hans Hofmann in Provincetown -- taught me how to paint through abstraction. I was pushing and pulling with the best of them. The idea that color -- and juxtapositions of color alone -- could create depth, was essential to this education. It was only in my last year of graduate school at Otis (1984-6) that I decided to "convert" to imagery. Today, the lessons of Hofmann's retinal process are still behind each painting. I'm always working warm-cold, Phthalo Blue vs. Van Dyke Brown, layering transparent glazes against each other.

LG: I arrived in LA originally because my father was writing movies; he wrote a few films with Steve Martin including "Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid" -- a parody of film noir that spliced the comedian into old classics like "Double Indemnity" to make a new comedic narrative. I think a lot of my ideas surrounding the notion of "nostalgia" started to get formed then. My father -- who died at age 52 in 1986 -- lived in the past - and my primary intimacy with him was watching late-night 1930's Warner Bros. movies - which became my nostalgia as well. The highlights of his childhood became my childhood: that compression, that transparency of time and visual culture, became my own generative fiction. I'm interested in how other artists have dealt with the notion of nostalgia and have a small blog dedicated to it.

LG: I think my obsession with industrial images and what I call the "Cult of Progress" was inspired by my early surroundings (Baltimore) and contact with an older generation that regarded the United States as an unflawed land of opportunity. I was in a "cusp" generation: still proud of the past but anxious about the present. By the time I was growing up in the late-70's the optimism bubble had burst: gas lines, the end of the Vietnam War - it wasn't pretty! The same factories portrayed in the WPA-era, for instance, looked much less attractive in the 70's. To me, a line of towering smokestacks belching into the clouds was a very ambivalent image; it meant people were working, but it also illustrated how the filthy end of the industrial revolution was coming to roost for my generation to clean up. Industry is glorious - and horrible. I'm always attracted to themes like that.

LG: A typical painting that straddles emotions, and a favorite image of mine from the current show, is "Sicily, 1944". Through my research, I found a book called "Flight to Everywhere", published in 1944 by Life magazine in cooperation with the War Office. Essentially, it documented a propaganda stunt: to show the public that, despite the war, the US still had dominion over the entire world. In it, a plane circumnavigated the globe, stopping in Allied air bases all along the way. Near the end of the journey, they made a stop in Sicily, which had just been secured by the US Army. That evening, the Nazis returned at night for a retaliatory raid, bombing the harbor of Palermo.

In the morning, when the photographer went out to look, he saw a golden dawn and an ominous cloud of ash hovering over the harbor. It was beautiful and tragic all at once -- so, for me, perfect. And, I think painting is the best medium to capture that couplet, as the layer of romance a painter can add complicates matters more than a photograph. It's really OK to have two different feelings about an image simultaneously. I always say, if you don't risk being misunderstood, it's not worth doing.

LG: I kind of meant for this current "Salon" exhibition to be like a "greatest hits" record - I didn't want to tuck all the work under a specific theme, like I usually do. Most of the pieces took less than a week to make, so I was able to say to myself: "paint whatever pleases you today". I was on a sabbatical from the University of Arizona and I had the time to fail and discard, without getting nervous. The two drawings in the show of the riot police were executed last summer - they took as long as ten paintings. After the buoyant, color world presented by the paintings, I wanted the viewer to be grounded back in reality by the starkness of the drawings.

In regards to the student exhibition, that was in response to an offer by my dealer, Lora Schlesinger, for me to curate the back gallery. I thought showing my current students and recent alumni would be fun. In terms of my teaching style, I don't create "acolytes" -- only one of the artists in the show deals with issues that are related to mine. I encourage abstraction in my classes, in fact, but my only interest is to find out what interests them and help them manifest that in art.

LG: I love writing about art -- in the short form. I write reviews -- 250-400 words -- that's how I'm most efficient. As far as writing informing my painting, I feel like own practice is a truculent beast that isn't much affected by my journalistic ventures, especially since I tend to choose sculpture or installations to write about. More than anything, I like research. A musty stack of post- war Soviet magazines gets me really excited! I'm always attracted to what a recent lecture at the Wende Museum called "The Politics of Happiness". I'm fascinated by how artists have collaborated with and visualized totalitarianism: the perfect, monolithic worlds they portray. I think a clandestine poster collecting tour to North Korea would be my dream trip.

LG: Right now, my work is going in 4-5 different directions. I realize this is detrimental to my career: I can't "brand" myself the way a lot of artists do. Yes, if you see an image of a train blasting out of a station, you can guess it's me. But, I'd just as soon paint portraits, a still life, a landscape with placid birches. All that's important is where from where the image is derived. And, with me, you can only be sure it's from a sinister context -- if those are birch trees, they're Soviet birch trees! Images like these - these kind of banal images -- are interesting to me because they seem familiar, but in fact they've come from obscure and forgotten contexts.

Lawrence Gipe Salon

Lora Schlesinger Gallery

January 12 - February 23, 2013

In the East Gallery: Emerging Artists curated by Lawrence Gipe: Nidaa Aboulhosn, Karen deClouet, Mena Ganey, Bobbi Gentry, Yubitza McCombs, Chris McGinnis