New Hampshire based painter and teacher Grant Drumheller, whose work is currently on view at the Prince Street Gallery, has recently been painting scenes of people relaxing in public spaces. More interested in light and gesture than in narrative, Drumheller takes a democratic approach to his figures, constructing them from matrices of small touches and generalizations set in light-infused compositions. His current exhibition includes several large beach scenes -- seen from a bird's eye view -- evoking a beach at Ascoli-Piceno Italy where the artist has taught during past summers.

I recently interviewed Drumheller and asked him more about his background and his approach.

Grant Drumheller: photo by Yuka Imata

John Seed Interviews Grant Drumheller

While earning both your BA and MA at Boston University you had some superb mentors: Philip Guston, James Weeks and Reed Kay. Can you tell me a bit about what you took away from each of them?

I was a sponge at BU and found the entire challenge of learning to draw and paint both delightful and painful. I was taught by a number of gifted faculty including those you mentioned. Jim Weeks drummed two dimensional design into me the most. I asked him if I could bring paint to class because I hadn't had him as a painting instructor, and I would do a three hour painting on paper twice a week. for a year . He wasn't a big talker but would give me pointers that really expanded my color. Things like "...put some colors in that black ", "...don't paint the individual forms just the 2 dimensional shapes: think of the early Greeks!" Then he'd pull out photos of the Parthenon Pediment friezes and show us how inclined they were to positive and negative parity. He tried to explain triads as a color notion to me, which I took a long time to understand. He really was aware of the materiality of light -- a sort of Californian sensibility -- whereas BU has a strong tradition of Cezanne structuralism.

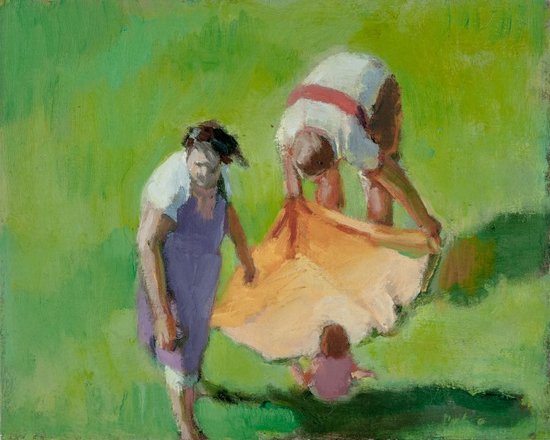

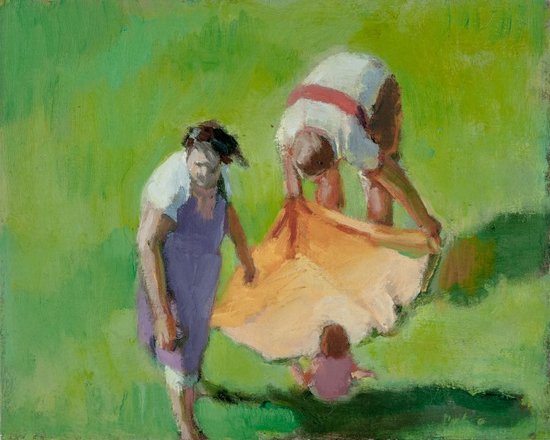

Grant Drumheller, "Orange Blanket," 2013, 8 x 10 inches, oil on linen

Reed Kay is the most committed teacher I ever knew. He also had absolute faith in me. I remember doing a painting in my flat manner of a model sitting for a portrait and he said, "Drumheller you could sign this and give it to Lord and Taylor for an ad; just give me the ear Drumheller!" He taught me to model form with warm and cool, to work from the inside out, and to use a kind of incisive and probing drawing. I learned I could have "a painting experience" in his class; a moment of knowing and forgetting. Reed always carried a pad and drew drawings for each student to clarify elements in their work. I have friends who kept every drawing: not me! They would grease up on the palette and I'd toss them. Now I wish I had them. His work is absolutely beautiful too, and once he retired from teaching, he had no regrets. He'd done it entirely and now was ready for the studio.

Grant Drumheller, "Women Talking," 2013, 8 x 10 inches, oil on linen

Philip Guston was my graduate mentor along with Jim Weeks as counterweight. I was in awe and mostly so speechless I couldn't breathe but I remember just about everything he said to me. He was so mad for Italy and quattrocento painting, it informed everything he spoke about, and he brought it into the present for us. The proscenium is a 14th century Italian convention he played with in most of his work. I would stay up all night making huge paintings before his crits just to get him to like me. Guston also pushed us to make paintings from our subconscious, to jump off the cliff in our work. It remains an ideal in my work, to be completely absorbed by the painting, to have it direct me. That mystery is a tantalizing thing: can I get that again? How do I get to that place in my work and have it happen again?

I got a Fulbright to live in Florence for a year and he cupped my cheek and said, "Good work, but you must live in Rome!" He wrote me a lovely letter to the then director of the American Academy in Rome to get me digs but they were full up with their own. He died shortly after that. I think his greatest compliment to me was during a critique. My studio mate was making hyper-realist paintings of skies and gas stations. He looked at me and said, referring to my tumbling and writhing figures that "when the revolution comes, they'll put her in charge of making the posters and you"ll go to prison!" I was recently at the Academy as a visitor and he came back to me in vivid ways; the specimen trees and sculptural fragments, the sense of scale and sky were in all the Roma paintings.

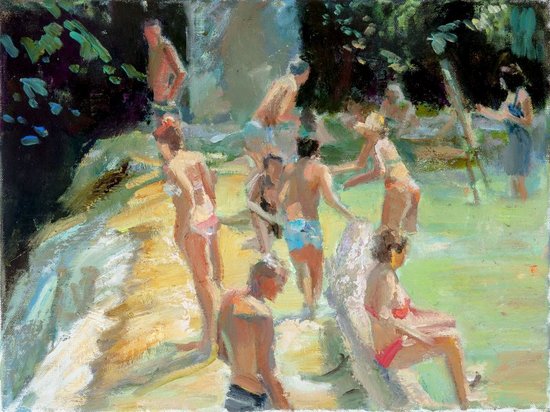

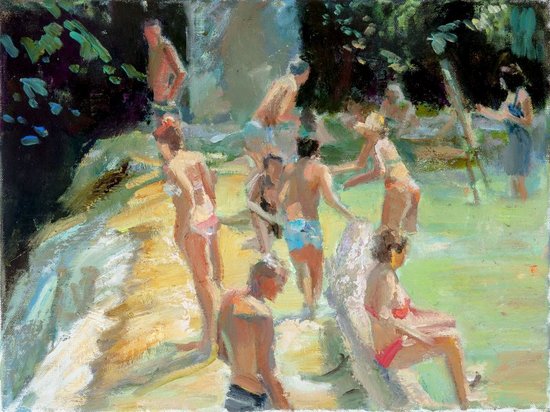

Grant Drumheller, "Bathers at the Falls," 2013, 12 x 16 inches, oil on linen

Your current show features a number of paintings of crowds seen from above. How did you become interested in that viewpoint and what are the problems of painting people from above?

I began painting still lifes of groups of toy animals at my feet on the studio floor, like big migrations. I had also spent some time in Rome filming from the 4th floor window of our hotel room in front of the Pantheon- all the comings and goings at various intervals. I guess the idea of painting that view also came from painting some of the large ruins in Rome with the inevitably small figures next to them. Then the next step was skipping the obvious monuments and just focusing on the figures and the paintings took off. I remember a time when I turned 21 and my parents celebrated with giving me a trip to the beach in Mexico. I took a parachute ride and as I rode up in the air the point of view was that of a bird. I find that the curve of my vision is often something I want to convey and not just the "crushed" space that one is familiar with from telephoto lens photography. So the dynamic of perspective and foreshortening the figures plays some part in the way I construct the paintings , also the geometry of the reserve -- what's behind and around -- and how it interacts with the verticals of the figures is an issue. I move the elements around a lot before things settle into place.

Grant Drumheller, "4th of July," 2013, 72 x 60 inches, oil on linen

You seem to work from both memory and observation: tell me about how you mix the two.

I painted mostly from memory for twenty years, inventing figures in narratives. I was pretty comfortable coming up with a gesture and my work from life complimented it. Sometimes the generality that ensued from invention needed to be better informed through observation and vice-versa; the drive in a gesture is a powerful dramatic element that is not often obtainable in the figure from observation. I became frustrated with work from imagination when I wanted to express something very precise, such as when my mother died and I spent two years painting self portraits, some wearing her effects. It was a very valuable experience. The large invented paintings of figures on beaches or in cities use both memory and observation.

Grant Drumheller, "Nude Bathers," 2013, 49.5 x 65 inches, oil on linen

If I told you that you are a Boston painter who paints like a Californian how would you reply?

I was born in Davis, California and remember as a baby lying on a blanket in the fragrant strawberry field behind the house. Whoever said babies don't have memories: don't believe them.

Grant Drumheller, "Boys Swimming," 2013, 8 x 10 inches, oil on panel

Who are some painters you admire?

Titian had it all: color, drawing, composing, and his transitions are unmatched in art. The other strange greats such as Bellini, Chardin, Picasso, de Chirico, Degas, Vuillard, Watteau are painters I look at: I have their cards over the sink. Contemporary art is hard to comment on; I feel like I am swimming among them. I will say that painting is both unique to itself and an art of its own.

"Grant Drumheller: New Paintings"

http://www.princestreetgallery.com/

530 West 25th Street, 4th Floor New York, New York

May 19 - June 15, 2013

I recently interviewed Drumheller and asked him more about his background and his approach.

While earning both your BA and MA at Boston University you had some superb mentors: Philip Guston, James Weeks and Reed Kay. Can you tell me a bit about what you took away from each of them?

I was a sponge at BU and found the entire challenge of learning to draw and paint both delightful and painful. I was taught by a number of gifted faculty including those you mentioned. Jim Weeks drummed two dimensional design into me the most. I asked him if I could bring paint to class because I hadn't had him as a painting instructor, and I would do a three hour painting on paper twice a week. for a year . He wasn't a big talker but would give me pointers that really expanded my color. Things like "...put some colors in that black ", "...don't paint the individual forms just the 2 dimensional shapes: think of the early Greeks!" Then he'd pull out photos of the Parthenon Pediment friezes and show us how inclined they were to positive and negative parity. He tried to explain triads as a color notion to me, which I took a long time to understand. He really was aware of the materiality of light -- a sort of Californian sensibility -- whereas BU has a strong tradition of Cezanne structuralism.

I got a Fulbright to live in Florence for a year and he cupped my cheek and said, "Good work, but you must live in Rome!" He wrote me a lovely letter to the then director of the American Academy in Rome to get me digs but they were full up with their own. He died shortly after that. I think his greatest compliment to me was during a critique. My studio mate was making hyper-realist paintings of skies and gas stations. He looked at me and said, referring to my tumbling and writhing figures that "when the revolution comes, they'll put her in charge of making the posters and you"ll go to prison!" I was recently at the Academy as a visitor and he came back to me in vivid ways; the specimen trees and sculptural fragments, the sense of scale and sky were in all the Roma paintings.

I began painting still lifes of groups of toy animals at my feet on the studio floor, like big migrations. I had also spent some time in Rome filming from the 4th floor window of our hotel room in front of the Pantheon- all the comings and goings at various intervals. I guess the idea of painting that view also came from painting some of the large ruins in Rome with the inevitably small figures next to them. Then the next step was skipping the obvious monuments and just focusing on the figures and the paintings took off. I remember a time when I turned 21 and my parents celebrated with giving me a trip to the beach in Mexico. I took a parachute ride and as I rode up in the air the point of view was that of a bird. I find that the curve of my vision is often something I want to convey and not just the "crushed" space that one is familiar with from telephoto lens photography. So the dynamic of perspective and foreshortening the figures plays some part in the way I construct the paintings , also the geometry of the reserve -- what's behind and around -- and how it interacts with the verticals of the figures is an issue. I move the elements around a lot before things settle into place.

I painted mostly from memory for twenty years, inventing figures in narratives. I was pretty comfortable coming up with a gesture and my work from life complimented it. Sometimes the generality that ensued from invention needed to be better informed through observation and vice-versa; the drive in a gesture is a powerful dramatic element that is not often obtainable in the figure from observation. I became frustrated with work from imagination when I wanted to express something very precise, such as when my mother died and I spent two years painting self portraits, some wearing her effects. It was a very valuable experience. The large invented paintings of figures on beaches or in cities use both memory and observation.

I was born in Davis, California and remember as a baby lying on a blanket in the fragrant strawberry field behind the house. Whoever said babies don't have memories: don't believe them.

Titian had it all: color, drawing, composing, and his transitions are unmatched in art. The other strange greats such as Bellini, Chardin, Picasso, de Chirico, Degas, Vuillard, Watteau are painters I look at: I have their cards over the sink. Contemporary art is hard to comment on; I feel like I am swimming among them. I will say that painting is both unique to itself and an art of its own.

"Grant Drumheller: New Paintings"

http://www.princestreetgallery.com/

530 West 25th Street, 4th Floor New York, New York

May 19 - June 15, 2013