The co-curators of "Face to Face:" Catherine Hess (left) and Paula Nutall (right)

with Hans Memling's "Portrait of a Man with a Coin of the Emperor Nero"

On loan from the collection of The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

The co-curators of "Face to Face:" Catherine Hess (left) and Paula Nutall (right)

with Hans Memling's "Portrait of a Man with a Coin of the Emperor Nero"

On loan from the collection of The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

"Face to Face: Flanders, Florence and the Renaissance," which has just opened at the Huntington, is what co-curator Catherine Hess calls "A gem of a show of gems." It features 29 paintings and about six illuminated manuscripts by artists such as Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, Pietro Perugino, and Domenico Ghirlandaio drawn from The Huntington's collections and those of several other institutions in the United States and Europe. Beyond offering Los Angelenos the chance to inspect a choice selection of Northern and Italian Renaissance treasures the exhibition also offers up a point of view: that Northern European paintings had more of an influence on Florentine art of the same period than has been previously acknowledged.

The exhibition also showcases a momentous reunion: It is the first time viewers in the Los Angeles area will be able to see The Huntington's prized "Virgin and Child" (ca. 1460) by Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1400-1464) displayed alongside its companion diptych panel, "Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ," on loan from the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. The pairing of the two panels is just one of many instances in the show in which groupings of works offer revelation and dialogue.

Rogier van der Weyden (Flemish, ca. 1400-1464). Left: Virgin and Child (ca. 1460).

Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Right: Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ (ca. 1460)

The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

Rogier van der Weyden (Flemish, ca. 1400-1464). Left: Virgin and Child (ca. 1460).

Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Right: Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ (ca. 1460)

The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

During the press preview I attended -- led by the co-curators -- we started by looking over the re-united van der Weyden triptych. Since portraiture is a major theme of exhibition I certainly looked hard at the faces of both the Virgin and of Philippe de Croÿ, the patron of the diptych. The Virgin struck me as both lovely and a bit remote: she seems unconcerned as a just slightly rascally infant Christ fiddles with the clasp of her bible. The golden glow that surrounds her suggests that she inhabits a Byzantine conception of heaven, slightly softened and deepened.

Witnessing from the right is Philippe de Croÿ, a Burgundian nobleman who Paula recommended to us as "handsome." Philippe, who is believed to have been around 25 at the time he was painted, is rendered in a fastidious manner that is certainly a bit idealized. He is also -- like other early Flemish portraits -- somewhat lacking in emotional suggestion. Under the fine craquelure of the panel he resembles a finely molded doe-eyed doll with a distinctly aqualine nose. Seen in a 3/4 view Philippe's gaze acknowledges the presence of the Virgin but he is also poised to turn towards us and serve as a noble intermediary between sanctity and reality.

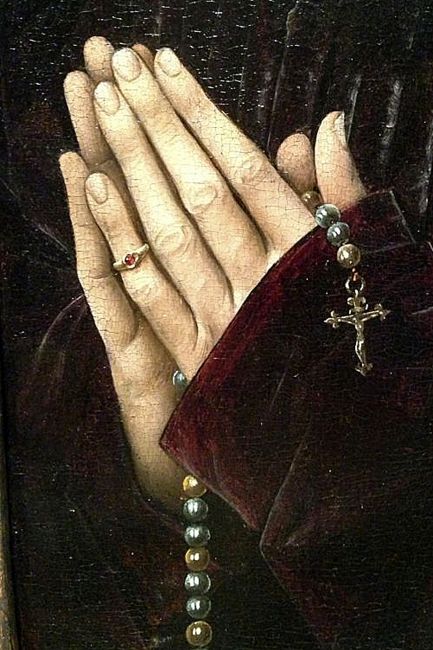

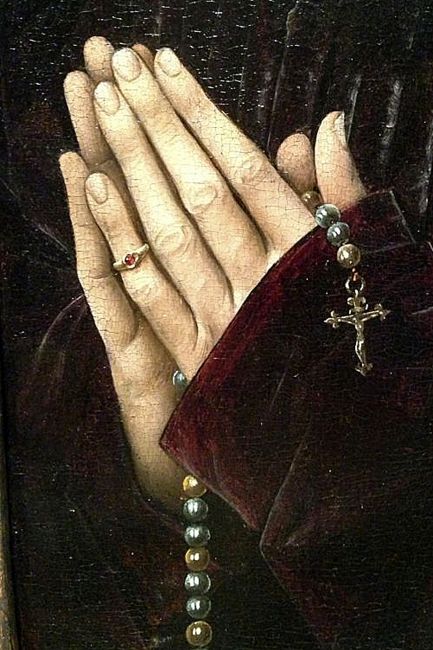

Detail: Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ (ca. 1460)

The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

Detail: Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ (ca. 1460)

The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

If Flemish painters of the mid-fifteenth century hadn't yet learned how to make their portraits convey psychological subtleties, they certainly get credit for their acute powers of observation. Van der Weyden gave a great deal of attention to Philip's praying hands, in which he found almost as much narrative potential as he had found in his features. Of course the artist may have painted the young nobleman with only cursory knowledge of the man's actual appearance.

Detail: Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ (ca. 1460)

The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

Detail: Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ (ca. 1460)

The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

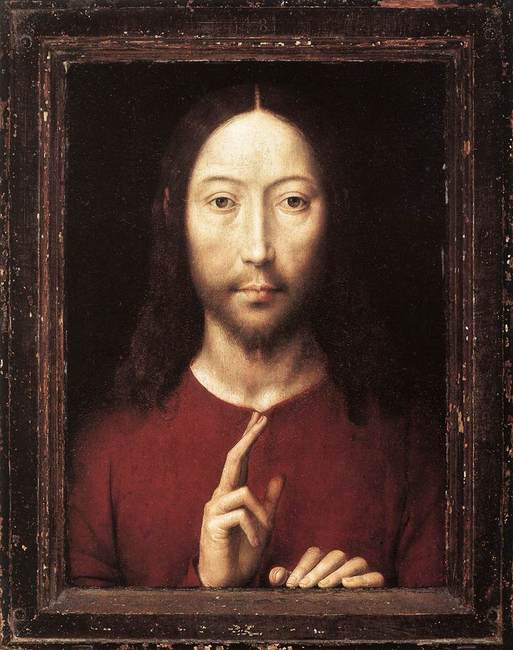

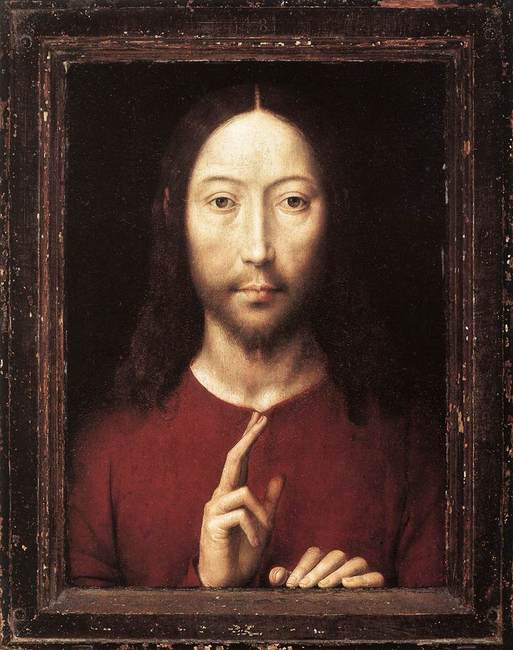

After looking over both van der Weyden panels as best I could I felt my short attention span kicking in. A bit impatiently I looked to my right and spotted "Christ Blessing," an 1481 oil on panel by Hans Memling that is just a bit over a foot high. From a few yards away it seemed to radiate a vulnerable humanity that defied my expectations.

Hans Memling (ca. 1430-1494), Christ Blessing, 1481

oil on panel, 13 1/8 × 9 7/8 in.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of William A. Coolidge.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Hans Memling (ca. 1430-1494), Christ Blessing, 1481

oil on panel, 13 1/8 × 9 7/8 in.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of William A. Coolidge.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

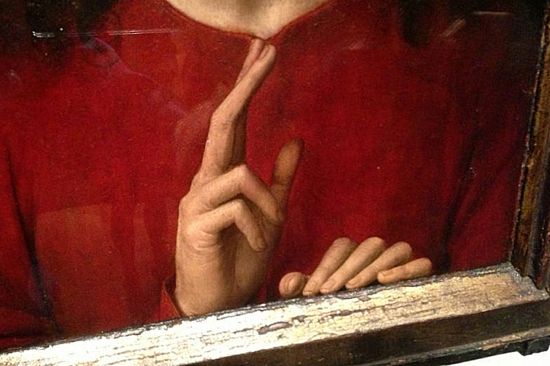

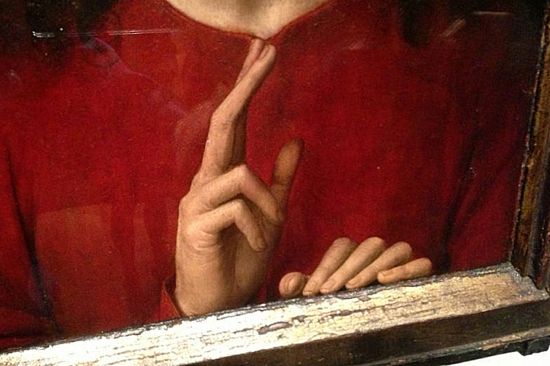

Upon approaching "Christ Blessing" I was struck its immense emotional subtlety. The face of Christ has a naturalistic softness that transmits a sense of knowing sadness: it moved and impressed me. But then I lowered my eyes and took in a detail that made the work come even more completely alive: Christ's hand rests on the edge of the frame in a virtuoso display of illusionistic oil painting.

Detail: Hans Memling (ca. 1430-1494), Christ Blessing, 1481

Detail: Hans Memling (ca. 1430-1494), Christ Blessing, 1481

The image of the hand really got to me: it was an epiphany that alerted me not only to the genius of Memling but also to the "moment" that this show represents. A few short decades before Leonardo completed the Mona Lisa it is clear that his artistic predecessors in the north were doing the hard work that cleared the way for the astonishing presence of his art. The power of that subtle hand -- resting on the edge between illusion and reality -- strikes me as every bit as brilliant and memorable as the Mona Lisa's smile. It breaches the barriers between Memling's world and ours and demolishes time.

The pleasant shock of Memling's painting woke me up to the beauties of the rest of the work in the show. Although I am used to looking at contemporary art -- which often broadcasts its messages with great immediacy -- I found myself slowing down and scanning the 15th century works on view in their entirety hoping for more subtle moments. One thing that really struck me was the exhibition's portraits often contained images of landscapes and still lifes that hinted at the kinds of images that would emerge in later centuries as established genres.

For example I was very charmed by Gerard David's "Virgin with the Milk Soup." Apparently Flemish collectors were too as there are some seven versions of this image which carries iconographic suggestions of salvation and redemption. She is the serene prototype of the window-lit secular beauties that Vermeer would paint two centuries later.

Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

oil on panel, 13 3/8 × 11 1/4 in.

Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Bianco, Genoa.

Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

oil on panel, 13 3/8 × 11 1/4 in.

Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Bianco, Genoa.

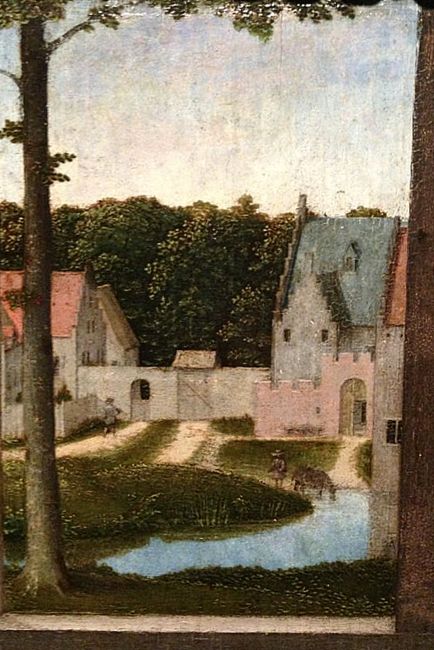

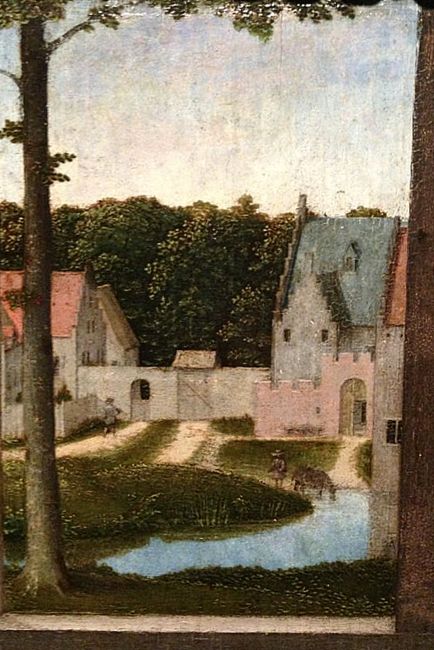

David's "Virgin" struck me as containing a host of paintings within a painting. His sensitive rendering of the milk soup and bread has the candor of a Chardin still life. The tiny vase of flowers on the shelf above the Virgin -- the flowers are meant to denote both sorrow and compassion -- is an image that will bloom into full complexity and become a genre in the hands of later Dutch masters. The gated village scene visible through the window is like a tiny John Constable landscape.

Detail: Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

Detail: Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

Detail: Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

Detail: Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

Detail: Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

Detail: Gerard David (ca. 1455-1523), Virgin with the Milk Soup, ca. 1510-15

"Face to Face" powerfully reveals the particular charms and aspirations of Late 15th century Flemish painting. The earnest responsibility and piety in the faces of the saints and nobility depicted in Flemish art is very touching and the world that surrounds them is painted with enchanting freshness. According to Paula Nutall linseed oil had been used in Northern painting as far back as the 12th century -- it wasn't discovered by the Van Eycks as the Italian writer Vasari claimed -- and oil paint had given Flemish artists a command of effects and moods that Renaissance Italian artists were only just beginning to attempt.

In the show's final "face to face" a wealthy Florentine couple are immortalized in separate but matching frames. Painted in tempera by Domenico Ghirlandaio -- who once counted Michelangelo as one of his apprentices -- the panels display a solemnity and clarity that signals the unmistakable influence of Northern art. Seen up close they have the fine hatch marks that Italian masters used to achieve detail in tempera. In that respect Ghirlandaio was still a bit behind his Burgundian peers.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494), "Portrait of a Man" and "Portrait of a Woman"

ca. 1490, tempera on panel, each is 20 3/8 × 15 5/8 in.

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494), "Portrait of a Man" and "Portrait of a Woman"

ca. 1490, tempera on panel, each is 20 3/8 × 15 5/8 in.

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the press release for "Face to Face" there is a quote from Michelangelo: he once said that Flemish paintings "will cause [the devout] to shed many tears." After seeing "Face to Face" you will have a broader sense of the power of Northern Renaissance art: and possibly you will leave the show with moist eyes as well.

"Face to Face: Flanders, Florence, and Renaissance Painting"

Sept. 28, 2013--Jan. 13, 2014

The Huntington: Library, Art Collection and Gardens

1151 Oxford Rd., San Marino, California

Visitor Information:

The Huntington is open to the public Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday from noon to 4:30 p.m.; and Saturday, Sunday, and Monday holidays from 10:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Summer hours (Memorial Day through Labor Day) are 10:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Closed Tuesdays and major holidays. Admission on weekdays: $20 adults, $15 seniors (65+), $12 students (ages 12-18 or with full-time student I.D.), $8 youth (ages 5-11), free for children under 5. Group rate, $11 per person for groups of 15 or more. Members are admitted free. Admission on weekends: $23 adults, $18 seniors, $13 students, $8 youth, free for children under 5. Group rate, $14 per person for groups of 15 or more. Members are admitted free. Admission is free to all visitors with advance tickets on the first Thursday of each month. Information: 626-405-2100 or

huntington.org.