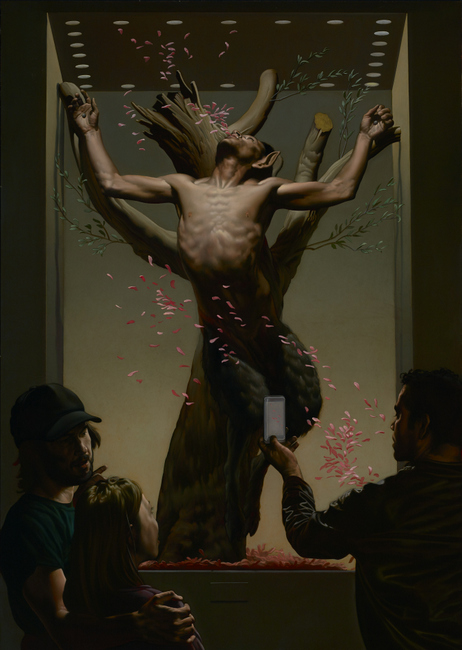

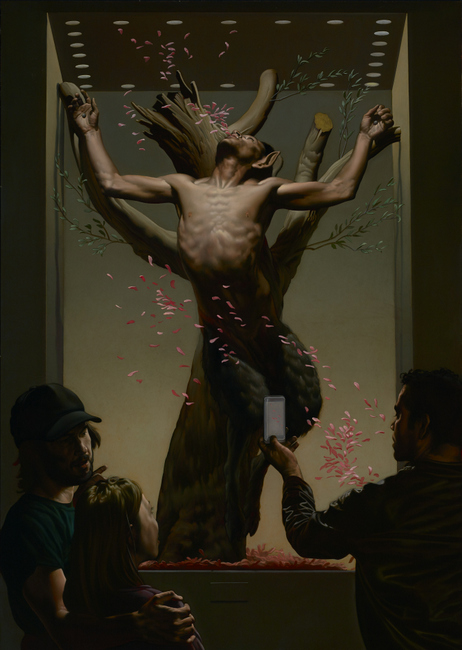

At Merry Karnowsky Gallery in Los Angeles painter Nicola Verlato is showing a suite of paintings that fantasize the many ways that pagan themes and elements might survive and reappear in contemporary society: in the exhibition's title painting a Satyr appears -- crucified -- as part of the display in a natural history museum. Dynamic, unsettling, and skillfully executed, Verlato's canvases dazzle and bewilder.

I recently interviewed Verlato, and asked him about his background, his subjects, and his views on art and culture.

Nicola Verlato: Photo by Yohko Verlato

John Seed Interviews Nicola Verlato

Nicola Verlato, "Pagan Pop," 70 x 50 inches, oil on linen

You have a remarkable background: how is it that you came to study at a young age with a monk/painter?

I grew up in a rural area in Northeastern Italy, between Verona and Vicenza. Even if we were basically isolated from the rest of the world, my parents had collected a lot of art books over the years. By the time I was seven, being very ambitious and quite stubborn, I wanted to learn to paint like Caravaggio, Correggio, Grunewald and Michelangelo, whose works I saw in those books.

That's when I started tormenting my parents to find someone, anyone, who could teach me to drawing and paint. Finally, a client of my family's winery said mentioned Fra Terenzio, a monk who taught people how to paint in his studio in the Franciscan monastery a few miles away.

I was nine then, but I still remember when I knocked on the door of his studio bringing my portfolio of drawings and a couple of paintings. Fra Terenzio opened the door and I said straight up: " I'm Nicola Verlato, and I want to become a painter!" He laughed, and for five consecutive summers I spent every single day in his studio.

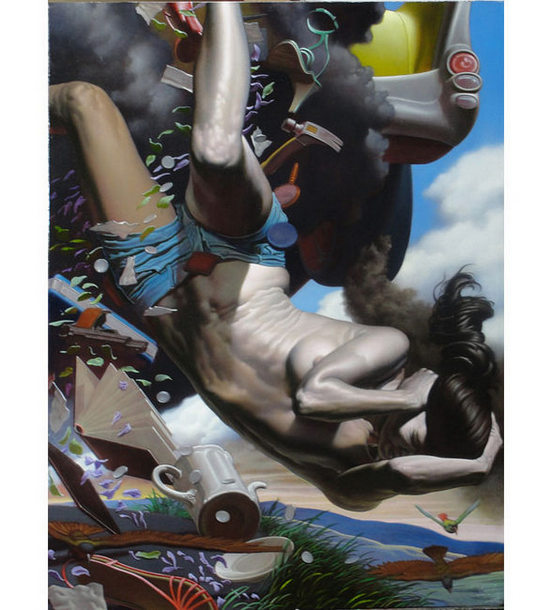

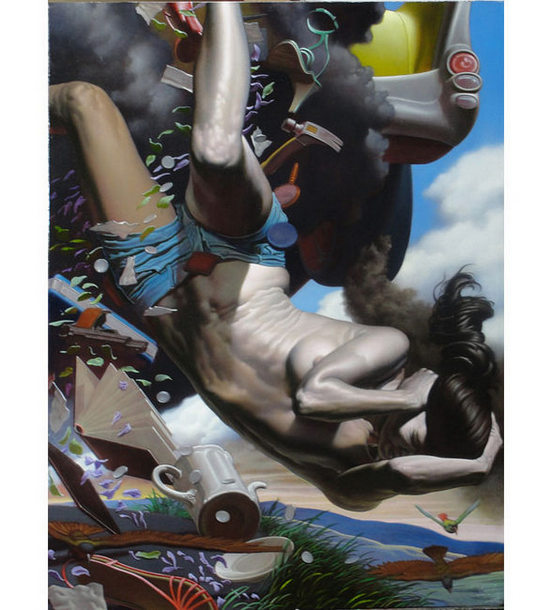

Nicola Verlato, "Breaking Point I," 25 x 19 inches, oil on canvas

Tell me about some of the occupations and interests you had before you focused on painting at the age of 28.

At 28, I became interested in exploring the field of contemporary art. Until then I had been working as a painter on commission for aristocratic families and affluent foreigners in Venice.

Although painting has been my main occupation since I was a kid, I've always expanded my creative research into other fields. It's as if everything I have done up until now was a preparatory study for the larger scale projects on which I'm currently working.

Growing up I learned the lute, classic guitar, piano and composition at the conservatories of Verona and Padua, until I picked up the electric guitar, the bass and keyboards out of my love for rock music. I also studied Architecture at the University of Venice. Throughout my career, I've worked in music videos and advertising campaigns, as a stage designer and a concept artist, and I've also written and directed a few experimental videos.

In 1993 I started to use 3D programs in the process of making my paintings. With these programs, which I still use today, I can more effectively control complex perspectives and introduce elaborate geometries. Sculpting has always accompanied my paintings. I actually conceive my paintings mostly as sculptural groups. In fact, I prepare modeling maquettes in clay, as did Tintoretto and other Renaissance artists.

Nicola Verlato, "David," 24 x 36 inches, oil on linen (not in show)

What made you decide to come to the United States, and how has your work been received here?

Moving to the US had been something I had always wanted to do. From early on in my life, I realized that Europe was incapable of creating new popular mythologies, which are what gives us humans the enthusiasm and will to live. While Europe may have certain social structures that are more advanced, it lacks the driving force that this country possesses.

I would like my work to be seen as my contribution as a single artist to the ongoing process of myth making of our time. The plurality of media and of cultures constantly creates new myths in this country. It was only natural for me to move here, where my work has been very well received, particularly in Los Angeles, the myth-making capitol. One of the most exciting things is that I've found a large community of other artists who share many aspects of my work. Surprisingly many of them are younger than I am, which I consider to be a very good sign!

You often work with themes such as "How the West Was Won," "Hooligans," and "Bachelors." Where do these themes and ideas come from?

I'm deeply immerged in the same ideas that constantly float through my mind. A lot of my inspiration derives from music. For example the series of paintings "How the West Was Won" owes its title to a Led Zeppelin record.

"The Bachelors" instead references Duchamp's "Large Glass. In that series I imagined that the bachelors of "Large Glass" were getting rid of all the paraphernalia, which was pinning them to the first floor, so that they could actually climb to the second floor and copulate with the bride. It was a complicate metaphor of the energy of painting imprisoned by photography during the 20th century and it's coming back through 3D programs and videogames....

The bachelors were, if you want, a more intellectualized version of "Hooligans". They are a visual but also philosophical representation of the enduring power of figurative painting.

The "Hooligans" series was my first solo show in Milano. I wanted to express the crazy energy of those people who can be seen as the other side of heroism-that-was.

Nicola Verlato, "From Madonna to Madonna," 70 x 50 inches, oil on linen

Is it correct to say that Caravaggio is the artist who most profoundly influenced you?

Most definitely in the beginning, and yes, I'm still very, very fond of his work. I think that the way I perceived the essence of painting was when I first saw Caravaggio's work. I was only seven, I was flipping through the pages of an art book in my father's collection when I saw a picture of the painting "The Flagellation" (in Naples). It blew my mind. Clutching the book, I ran to my mother to share my discovery. I think it was the incredible power of that image, its presence, that struck my mind most. It was more alive than life itself.

Nicola Verlato, "Off the Grid," 24 x 36 inches, oil on linen

What does your work have to say about America and American culture?

I think most of my work is related to American culture. I enjoy playing with the possibility of celebrating it through the techniques of classical art. It's something that hasn't been done yet and I think now is the time to do it.

For me, American culture is all about the narrative arts: music, movies and TV shows, comic books and cartoons. These are all forms of Pop Culture. The realm of Fine Arts is sealed in an elitist prison in America, and thus in the rest of the world. This keeps art from participating in any substantial cultural process. It's as if the power and reach of art is frozen in a sort of limbo, while other media create narrative masterpieces. I believe that it is time to allow Fine Arts to work together with these narrations and to transform into permanent, iconic forms. This is what I am trying to do with the current creation of my monumental projects. These would be ideally located in the actual places where the mythic, legendary events that inspired them took place.

I believe that the reason this hiatus has been placed on the figurative arts lies in a suspicious attitude towards them. This stems from the Puritanical background of American culture. A similar process already happened over centuries during the Middle Ages in Europe and before then in Archaic Greece. So there's really nothing to worry about, there's still hope for change...

Nicola Verlato, "Banned," 24 x 36 inches, oil on linen

Your work is full of movement, dynamism and energy. Has it always been that way?

Yes! I hate figurative paintings in which nothing happens and where no stories are told. They seem to be the figurative version of abstract art. But while abstract art doesn't include any figures at all, these figurative versions of abstract art use figures as a mere compositional tool. The artists who paint them expect to not generate any sort of emotional response in the viewer. In doing so, the have a much more negative effect figurative art than abstract art itself.

There are other reasons why I like to compose my paintings in very dynamic and energetic ways. In the end it's all about involving the viewer as much as possible in experiencing the impact of the story that my painting is telling. Painting, for me, is the crystallized version of story telling.

Nicola Verlato, "The Haunting of the Haunted Painting," 44 x 80 inches, oil on canvas

Tell me about your book.

I'm very happy about my new book "From Verona with Rage" published by Gingko Press. It very accurately describes the evolutionary phase my carrier is in now. After creating a large selection of paintings over the last seven years, I'm beginning an exciting new chapter of larger scale projects that will involve painting, sculpture, architecture and music. As a sort of preview, the book illustrates this latest phase of mine by showcasing some of the materials I'm currently developing.

What else would you like people to know about you and your art?

A couple of museums -- and although I'd like to I can't be more specific -- have recently reached out to me asking for shows of my new monumental work. I would say that, if you're interested in my work, stay tuned! I've just gotten started and there are gonna be a lot of surprises...

Nicola Verlato: Pagan Pop

September 7-28, 2013

The Merry Karnowsky Gallery (Main Gallery)

170 S. La Brea Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90036

I recently interviewed Verlato, and asked him about his background, his subjects, and his views on art and culture.

I grew up in a rural area in Northeastern Italy, between Verona and Vicenza. Even if we were basically isolated from the rest of the world, my parents had collected a lot of art books over the years. By the time I was seven, being very ambitious and quite stubborn, I wanted to learn to paint like Caravaggio, Correggio, Grunewald and Michelangelo, whose works I saw in those books.

That's when I started tormenting my parents to find someone, anyone, who could teach me to drawing and paint. Finally, a client of my family's winery said mentioned Fra Terenzio, a monk who taught people how to paint in his studio in the Franciscan monastery a few miles away.

I was nine then, but I still remember when I knocked on the door of his studio bringing my portfolio of drawings and a couple of paintings. Fra Terenzio opened the door and I said straight up: " I'm Nicola Verlato, and I want to become a painter!" He laughed, and for five consecutive summers I spent every single day in his studio.

At 28, I became interested in exploring the field of contemporary art. Until then I had been working as a painter on commission for aristocratic families and affluent foreigners in Venice.

Although painting has been my main occupation since I was a kid, I've always expanded my creative research into other fields. It's as if everything I have done up until now was a preparatory study for the larger scale projects on which I'm currently working.

Growing up I learned the lute, classic guitar, piano and composition at the conservatories of Verona and Padua, until I picked up the electric guitar, the bass and keyboards out of my love for rock music. I also studied Architecture at the University of Venice. Throughout my career, I've worked in music videos and advertising campaigns, as a stage designer and a concept artist, and I've also written and directed a few experimental videos.

In 1993 I started to use 3D programs in the process of making my paintings. With these programs, which I still use today, I can more effectively control complex perspectives and introduce elaborate geometries. Sculpting has always accompanied my paintings. I actually conceive my paintings mostly as sculptural groups. In fact, I prepare modeling maquettes in clay, as did Tintoretto and other Renaissance artists.

Moving to the US had been something I had always wanted to do. From early on in my life, I realized that Europe was incapable of creating new popular mythologies, which are what gives us humans the enthusiasm and will to live. While Europe may have certain social structures that are more advanced, it lacks the driving force that this country possesses.

I would like my work to be seen as my contribution as a single artist to the ongoing process of myth making of our time. The plurality of media and of cultures constantly creates new myths in this country. It was only natural for me to move here, where my work has been very well received, particularly in Los Angeles, the myth-making capitol. One of the most exciting things is that I've found a large community of other artists who share many aspects of my work. Surprisingly many of them are younger than I am, which I consider to be a very good sign!

You often work with themes such as "How the West Was Won," "Hooligans," and "Bachelors." Where do these themes and ideas come from?

I'm deeply immerged in the same ideas that constantly float through my mind. A lot of my inspiration derives from music. For example the series of paintings "How the West Was Won" owes its title to a Led Zeppelin record.

"The Bachelors" instead references Duchamp's "Large Glass. In that series I imagined that the bachelors of "Large Glass" were getting rid of all the paraphernalia, which was pinning them to the first floor, so that they could actually climb to the second floor and copulate with the bride. It was a complicate metaphor of the energy of painting imprisoned by photography during the 20th century and it's coming back through 3D programs and videogames....

The bachelors were, if you want, a more intellectualized version of "Hooligans". They are a visual but also philosophical representation of the enduring power of figurative painting.

The "Hooligans" series was my first solo show in Milano. I wanted to express the crazy energy of those people who can be seen as the other side of heroism-that-was.

Most definitely in the beginning, and yes, I'm still very, very fond of his work. I think that the way I perceived the essence of painting was when I first saw Caravaggio's work. I was only seven, I was flipping through the pages of an art book in my father's collection when I saw a picture of the painting "The Flagellation" (in Naples). It blew my mind. Clutching the book, I ran to my mother to share my discovery. I think it was the incredible power of that image, its presence, that struck my mind most. It was more alive than life itself.

I think most of my work is related to American culture. I enjoy playing with the possibility of celebrating it through the techniques of classical art. It's something that hasn't been done yet and I think now is the time to do it.

For me, American culture is all about the narrative arts: music, movies and TV shows, comic books and cartoons. These are all forms of Pop Culture. The realm of Fine Arts is sealed in an elitist prison in America, and thus in the rest of the world. This keeps art from participating in any substantial cultural process. It's as if the power and reach of art is frozen in a sort of limbo, while other media create narrative masterpieces. I believe that it is time to allow Fine Arts to work together with these narrations and to transform into permanent, iconic forms. This is what I am trying to do with the current creation of my monumental projects. These would be ideally located in the actual places where the mythic, legendary events that inspired them took place.

I believe that the reason this hiatus has been placed on the figurative arts lies in a suspicious attitude towards them. This stems from the Puritanical background of American culture. A similar process already happened over centuries during the Middle Ages in Europe and before then in Archaic Greece. So there's really nothing to worry about, there's still hope for change...

Yes! I hate figurative paintings in which nothing happens and where no stories are told. They seem to be the figurative version of abstract art. But while abstract art doesn't include any figures at all, these figurative versions of abstract art use figures as a mere compositional tool. The artists who paint them expect to not generate any sort of emotional response in the viewer. In doing so, the have a much more negative effect figurative art than abstract art itself.

There are other reasons why I like to compose my paintings in very dynamic and energetic ways. In the end it's all about involving the viewer as much as possible in experiencing the impact of the story that my painting is telling. Painting, for me, is the crystallized version of story telling.

I'm very happy about my new book "From Verona with Rage" published by Gingko Press. It very accurately describes the evolutionary phase my carrier is in now. After creating a large selection of paintings over the last seven years, I'm beginning an exciting new chapter of larger scale projects that will involve painting, sculpture, architecture and music. As a sort of preview, the book illustrates this latest phase of mine by showcasing some of the materials I'm currently developing.

A couple of museums -- and although I'd like to I can't be more specific -- have recently reached out to me asking for shows of my new monumental work. I would say that, if you're interested in my work, stay tuned! I've just gotten started and there are gonna be a lot of surprises...

Nicola Verlato: Pagan Pop

September 7-28, 2013

The Merry Karnowsky Gallery (Main Gallery)

170 S. La Brea Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90036