It's too bad that "Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966," won't be traveling to New York after it closes its run at San Francisco's De Young Museum on September 29th. The show will be seen at one more venue -- it will be at the Palm Springs Museum from October 26th through February 16th of next year -- but if it were to travel to Manhattan the exhibition would certainly create a boom in the art publishing industry: the history of American painting in the 1950s and 1960s would need to be re-written with Richard Diebenkorn and California postwar art occupying far more prominent positions.

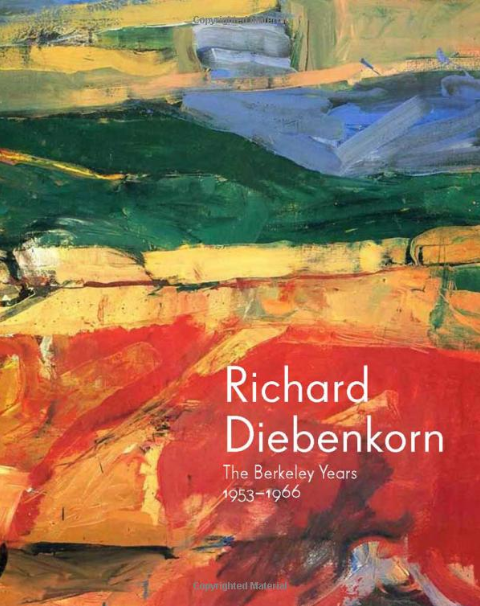

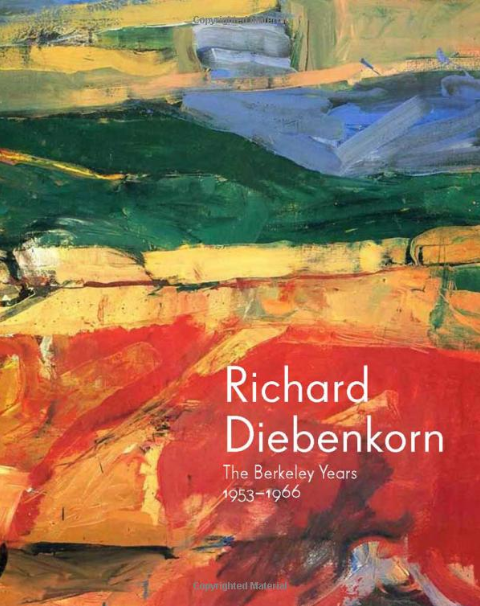

"Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966"

With essays by Timothy Anglin Burgard, Steven Nash and Emma Acker.

During the same period when East Coast critics were lavishing praise on three successive movements -- Abstract Expressionism, Pop and Minimalism -- native Californian Richard Diebenkorn stayed on the West Coast hybridizing and synthesizing. He grappled with Abstract Expressionism on his own terms, barely noticed Pop and then infused his Ocean Park paintings with a respectful injection of Minimalism. The works Diebenkorn made during his years in Berkeley reflect his artistic dialogues with Edward Hopper, Northern Expressionism, the work of Bay Area colleagues and the French lineage represented by Cezanne, Matisse and Bonnard.

Diebenkorn isn't a good candidate for a full biography as his bourgeois and stable personal life leaves little to gossip about but his mid-career paintings stand ready to reveal a great deal about his fascinating inner life. "The Berkeley Years" contains both masterpieces and quirky unresolved works: viewed in concert they offer revelations into the artist's thought processes and predilections. This exhibition is especially precious in the sense that it displays tensions and doubts that were later increasingly veiled behind a screen of privacy in the emotionally opaque Ocean Park series.

I had planned to wait to see the show until it came to Palm Springs but fortunately my friend Mitchell Johnson convinced me that I need to get on a plane and see it sooner. Mitchell, a painter who has looked very acutely at modern and contemporary painting, sent me an e-mail a few weeks ago telling me the show had affected him deeply. The chance to walk through the show with Mitchell proved irresistible and I booked my flight.

Mitchell Johnson with his painting "The Fence," 2010, oil on linen, 84 x 56 inches

Photo: John Seed

The show begins with Diebenkorn's abstract "Berkeley" series which responds mainly to the Abstract Expressionist models provided by the pioneering artists Clyfford Still and Willem de Kooning. As Mitchell and I scanned these works it became clear that they were that Diebenkorn had a very different temperament than the avant grade pioneers he was influenced by. Mitchell Johnson's observation is that "Diebenkorn is the introverted foil to the attack you see in Clyfford Still's egomaniacal work."

Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993)

Berkeley #44, 1955 Oil on canvas, 59 x 64 in. (149.9 x 162.6 cm)

Private collection © 2013 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation. All rights reserved.

I think Mitchell has it right. Even when Diebenkorn was flinging paint or applying it with some degree of frenzy there is always a sense of schematic restraint in his compositions. Diebenkorn's works lack the elevated confidence of fanaticism and the finesse of charlatanism. His relatively even tempered "Berkeley" canvases are tempered by a sense of intellectual and emotional reticence that is lacking in De Kooning's oedipal tantrums and Still's brutal crags. To put it another way, Diebenkorn appears to have had some principled doubts about action painting, but he gave it a try and his work gained confidence and vitality from his engagement with it.

Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993)

"Figure on a Porch," 1959, Oil on canvas, 57 x 62 in. (144.8 x 157.5 cm)

Oakland Museum of California, gift of the Anonymous Donor Program of the American Federation of the Arts, A60.35.5

© 2013 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation. All rights reserved.

By 1955 Diebenkorn was experimenting with figuration, influenced by the contrarian return to the figure that his great friend David Park had made. "For someone who was intending to continue as an abstract painter I was clearly consorting with the wrong company," Diebenkorn later acknowledged. The representational paintings he made during the late 1950s and early 1960s show the influence of his Bay Area peers -- especially David Park and Elmer Bischoff -- and they remain Diebenkorn's most memorable and revealing works. In later years Diebenkorn spoke of the human figure having often been a "problem" that needed to be solved. Responding to the challenge of the figure eventually brought out some of Diebenkorn's most deft and elegant brushwork.

Making the figures "work" in their painted surroundings was always a positive problem and many of his solutions are brilliant and original. Sometimes Diebenkorn's formalist instincts overwhelmed his feelings about the figure and the resulting paintings could be a bit chilly: during his lifetime Diebenkorn was often annoyed by what critics had to say about a perceived emotional distance between the artist and his human subjects. In truth, even some of his most beautiful figures emanate at least a hint of isolation. I find Mitchell Johnson's take on this dynamic compelling:

Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993)

Interior with Doorway, 1962, Oil on canvas, 70 3/8 x 59 1/2 in. (178.8 x 151.1 cm)

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Henry D. Gilpin Fund, 1964.3

© 2013 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation. All rights reserved.

After Park's death in 1960 Diebenkorn seemed to find his own distinctive subject matter which began to include vacant interiors and views of urban landscapes. With the human figure absent absent Diebenkorn became more improvisational. One of the joys of the de Young show is to scan the surface of paintings like "Interior with Doorway" of 1962 and to see how the painting fell into place when the artist's final edits -- such as the dark fields of negative space around the folding chair -- cause the composition to lock into place. I couldn't stop looking at the gorgeous hints of colors pulsing through the chair's legs: they are traces of something beautiful that will never be fully revealed.

Detail of "Interior with Doorway."

Some of the paintings in "The Berkeley Years" show the mixed results that occurred as Diebenkorn felt free to experiment with his subject matter. There is a very odd painting of a cluttered table with a Guston-like hand holding a cigarette reaching towards it. There is also a stunning picture of a studio utility sink that is a masterpiece of zen brushwork. Diebenkorn's confident and masterful rendering of the zig-zagging drainpipes under the sink has more abstract vitality than most Franz Kline paintings.

Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993)

Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad, 1965, Oil on canvas, 73 x 84 in. (185.4 x 213.4 cm)

Private collection

© 2013 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation. All rights reserved.

After returning from a trip to Russia 1964 where he viewed the incomparable Matisse paintings on view at the Pushkin Museum and at the Hermitage Diebenkorn indulged in a final artistic apprenticeship, painting homages to Matisse including "Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad." Diebenkorn learned a great deal from this final deep exploration and was especially sensitive to the stylizations and abstract tendencies in Matisse's works. By 1966 Diebenkorn -- who knew when not to linger -- had absorbed what he needed to and was ready to move on.

As Mitchell and I were preparing to leave the exhibition we stood in the final room and looked through a wide doorway into the well lit gift shop crammed with shrink-wrapped catalogs and Diebenkorniana. To the left of the doorway was a lovely but fussy painting of the artist's wife: "Seated Figure with a Hat." To the right of the door was a brave but awkward figure of a standing female nude: "Nude on Blue Ground." The two paintings seemed to say the same thing: Diebenkorn had taken the figure towards two dead ends. In a perfect world "The Berkeley Years" would lead into last year's OCMA retrospective of the Ocean Park series and not the gift shop.

Picasso once said that "the secret to creativity is knowing how to hide your sources." In his final "Ocean Park" paintings Diebenkorn certainly did more to hide his sources: or it might be better to say that he absorbed and sublimated them. Behind the veils and scumbles of their surfaces are vestigial traces of the influences, problems and subjects that he grappled with during his years of living in Berkeley.

Like other successful painters Diebenkorn has inspired too many epigones: lesser Diebenkorns who have learned from his surfaces and subjects but not from his intellectual scrupulousness. I hope that serious painters who see "The Berkeley Years" will realize that what they need to borrow from Diebenkorn is the studiousness and patience with which he chose and learned from his peers and predecessors. They also need to pay close attention to the fact that at a certain point he subsumed his sources and became Richard Diebenkorn: an utterly unique figure. "Be yourself," Oscar Wilde advised, "everyone else is taken."

I honestly think that "Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966" is the best single show I have ever seen about an artist's career development. Diebenkorn was never part of the leading edge of American art but by thinking through a wide range of influences and ideas he ultimately out-distanced many of his showier peers. In an era when too many American artists began to believe the lofty praise that came their way Richard Diebenkorn managed to stay humble and curious. He had enough doubts about himself -- and about his art -- to be truly great.

Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966

The de Young Museum

Golden Gate Park

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive

San Francisco, CA 94118

deyoungmuseum.org

415-750-3600

Museum Hours

Tuesday-Sunday, 9:30 am-5:15 pm

Friday (March 29-November 29, 2013) 9:30 am-8:45 pm

Closed Mondays

Admission

Tuesday-Friday: $20 adults; $17 seniors; $16 college students with ID; $10 youths 6-17.

Diebenkorn isn't a good candidate for a full biography as his bourgeois and stable personal life leaves little to gossip about but his mid-career paintings stand ready to reveal a great deal about his fascinating inner life. "The Berkeley Years" contains both masterpieces and quirky unresolved works: viewed in concert they offer revelations into the artist's thought processes and predilections. This exhibition is especially precious in the sense that it displays tensions and doubts that were later increasingly veiled behind a screen of privacy in the emotionally opaque Ocean Park series.

I had planned to wait to see the show until it came to Palm Springs but fortunately my friend Mitchell Johnson convinced me that I need to get on a plane and see it sooner. Mitchell, a painter who has looked very acutely at modern and contemporary painting, sent me an e-mail a few weeks ago telling me the show had affected him deeply. The chance to walk through the show with Mitchell proved irresistible and I booked my flight.

Making the figures "work" in their painted surroundings was always a positive problem and many of his solutions are brilliant and original. Sometimes Diebenkorn's formalist instincts overwhelmed his feelings about the figure and the resulting paintings could be a bit chilly: during his lifetime Diebenkorn was often annoyed by what critics had to say about a perceived emotional distance between the artist and his human subjects. In truth, even some of his most beautiful figures emanate at least a hint of isolation. I find Mitchell Johnson's take on this dynamic compelling:

The really great figures are so accessible and compelling in their composition, but they are also tragic. You feel the shapes surrounding the figures harnessing them into the composition but also pressing on them like weights of realization. They have an existential quality that separates them more and more clearly as time goes by from Diebenkorn's contemporaries.Mitchell also feels strongly that Diebenkorn's sense of doubt was an essential quality: "I think this is the greatest message of his work: that on some level, the world doesn't deliver itself to you, it doesn't preexist. You make sense of it, you make your world."

As Mitchell and I were preparing to leave the exhibition we stood in the final room and looked through a wide doorway into the well lit gift shop crammed with shrink-wrapped catalogs and Diebenkorniana. To the left of the doorway was a lovely but fussy painting of the artist's wife: "Seated Figure with a Hat." To the right of the door was a brave but awkward figure of a standing female nude: "Nude on Blue Ground." The two paintings seemed to say the same thing: Diebenkorn had taken the figure towards two dead ends. In a perfect world "The Berkeley Years" would lead into last year's OCMA retrospective of the Ocean Park series and not the gift shop.

Picasso once said that "the secret to creativity is knowing how to hide your sources." In his final "Ocean Park" paintings Diebenkorn certainly did more to hide his sources: or it might be better to say that he absorbed and sublimated them. Behind the veils and scumbles of their surfaces are vestigial traces of the influences, problems and subjects that he grappled with during his years of living in Berkeley.

Like other successful painters Diebenkorn has inspired too many epigones: lesser Diebenkorns who have learned from his surfaces and subjects but not from his intellectual scrupulousness. I hope that serious painters who see "The Berkeley Years" will realize that what they need to borrow from Diebenkorn is the studiousness and patience with which he chose and learned from his peers and predecessors. They also need to pay close attention to the fact that at a certain point he subsumed his sources and became Richard Diebenkorn: an utterly unique figure. "Be yourself," Oscar Wilde advised, "everyone else is taken."

I honestly think that "Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966" is the best single show I have ever seen about an artist's career development. Diebenkorn was never part of the leading edge of American art but by thinking through a wide range of influences and ideas he ultimately out-distanced many of his showier peers. In an era when too many American artists began to believe the lofty praise that came their way Richard Diebenkorn managed to stay humble and curious. He had enough doubts about himself -- and about his art -- to be truly great.

Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years, 1953-1966

The de Young Museum

Golden Gate Park

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive

San Francisco, CA 94118

deyoungmuseum.org

415-750-3600

Museum Hours

Tuesday-Sunday, 9:30 am-5:15 pm

Friday (March 29-November 29, 2013) 9:30 am-8:45 pm

Closed Mondays

Admission

Tuesday-Friday: $20 adults; $17 seniors; $16 college students with ID; $10 youths 6-17.