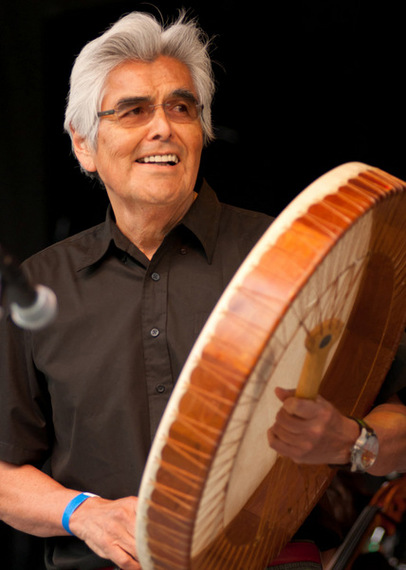

Since raising the first totem pole on Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands) in over 90 years at the age of 22 he has become a leading figure in the Haida Renaissance, creating jewelry, sculpture, drums, paintings, totem poles and wood carvings, and also co-founding a dance troupe with his brother Reg. Davidson -- whose Haida name is Guud San Glans which means Eagle of the Dawn -- is also very interested in expanding the circle of his own culture to intersect and join with the larger circle of international culture.

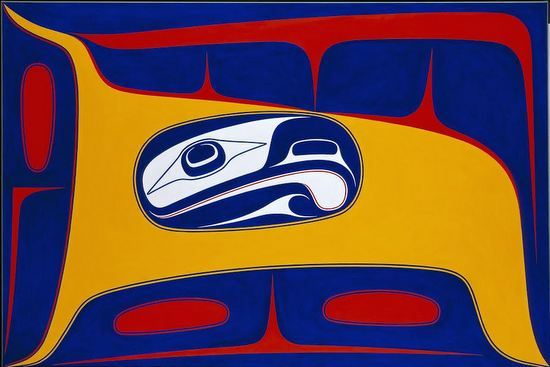

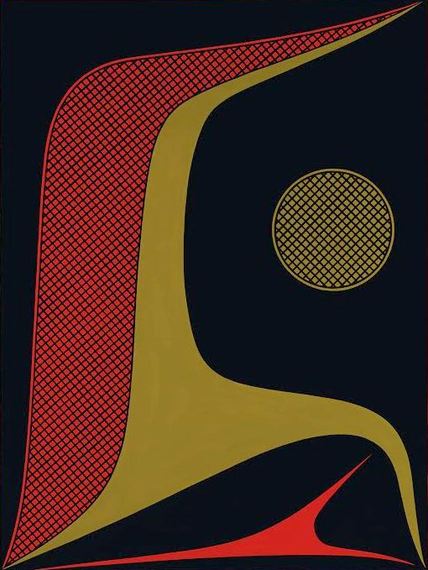

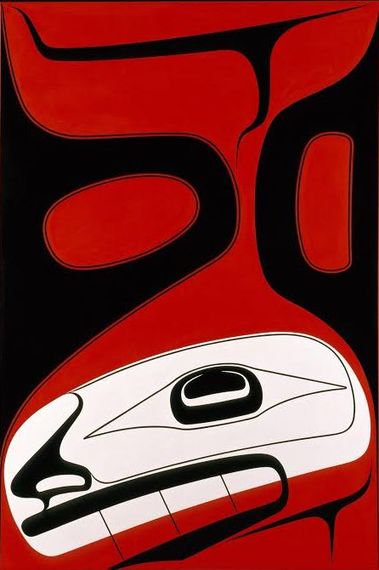

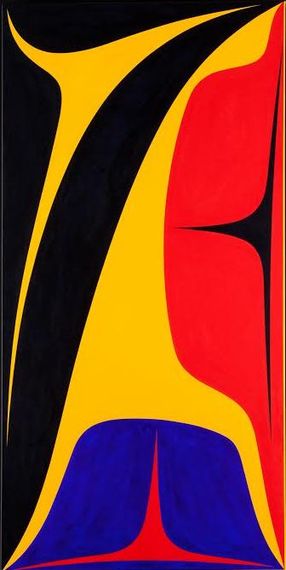

Davidson's recent acrylic on canvas paintings represent his attempt to bring imagery rooted in the Haida past towards contemporaneity, a project that Barbara Brotherton -- the curator of Robert Davidson: Abstract Impulse -- acknowledges and supports.

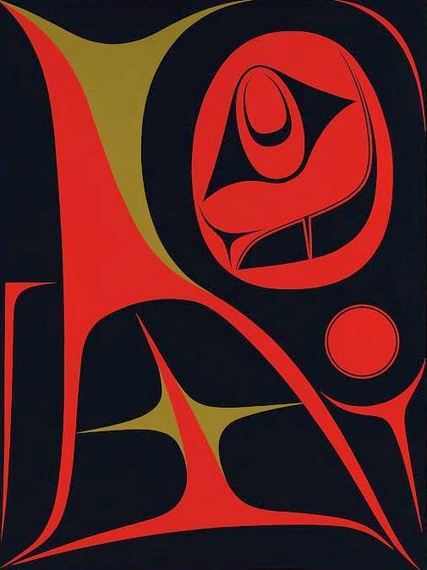

As Brotherton explains: "We purposely placed the exhibition within our modern and contemporary galleries -- not the native American galleries -- in order to communicate the message that this work is contemporary. One of the challenges is revealing how First Nations art can have elements of tradition but still be modern." In particular, Davidson's recent acrylic on canvas paintings display glyphic elements that are simultaneously Haida-inpsired and personal to the artist. Boldly conceived, graphically crisp and strikingly inventive, Davidson's paintings have entered a new phase, initiating a conversation with contemporary abstraction.

"I want my images to have their own strength," Davidson recently told writer Mark Follman, "so that a person does not have to have any knowledge about Northwest Coast art to appreciate them."

I recently spoke to Robert Davidson and asked him about his beginnings, his imagery and his artistic practice.

John Seed Interviews Robert Davidson

It feels timely right now. There is also a show of Charles Edenshaw (1839-1920) at the Vancouver Art Gallery and his work echoes all the centuries of development of the Haida art form. He expanded on the Haida tradition - that great art form that existed prior to European contact - and then it declined.

My dad pushed me into carving: he was adamant that I begin carving at age 13. When I first started in 1959 there were just a handful of carvers: we didn't label them artists.

Yes, I have. I left home in 1965 and had one job for two days in a cannery, but that is it. There were a lot of lean days in the early years. I learned one of the great lessons from my grandfather: when you don't have orders (commissions) just keep working. That was the best advice ever. The paintings that I am doing now are not commissioned.

It took me a long time to understand Haida art and culture. There are two surviving Haida villages and photos taken in the 1880s show them lined with totem poles: there were no less than 50 of them in Massett. When I came around there was nothing. There wasn't much talk about culture or dances because potlatches -- public events hosted by chiefs to make declarations and offer gifts -- were then prohibited by law.

Our traditional names were given to us at a potlatch. When I would visit home as a young man I found that people were not being given Haida names. I hosted a potlatch in 1981 and encouraged people to give Haida names to their children and grandchildren. I had realized that an artist could help fill the cultural void. Works of art were not the only mediums: the potlatch was also a medium.

It took me time to realize that there is more to the art: art and ceremony are the only languages we have. The designs (abstractions) that I get really excited about are those that are drawn from the lessons from the old masters of Haida art.

In Haida art there are two main alphabet forms: ovoid and u-shaped: this painting includes a U form. At the very bottom left - inside the U - the green slits are the negative space between the forms of teeth. The top right is part of the oval "being" and there is an eye in there. I don't know what the being is. I like to think of my creations on one of two levels: conscious or sub-conscious. After you have put in twenty thousand hours of work into your art eventually everything is intuitive and comes from the subconscious. That is where my inspiration comes from.

I really appreciate that. We were not being recognized as artists per say: we have never been in a contemporary setting. That is slowly changing today in Vancouver.

How do you feel about your paintings at this point in your life and career?

I guess I am really excited: it has taken me this long to feel free. When my daughter was three or four she was in the studio painting with me too. She asked: "How come you don't paint for fun?" Now I am having fun.

Photos of Robert Davidson's artwork by Kenji Nagai

Robert Davidson: Abstract Impulse

The Seattle Art Museum

1300 First Avenue Seattle, WA 98101-2003

November 16, 2013-February 16, 2014