Whenever I meet people I always approach them from the standpoint of the most basic things we have in common. We each have a physical structure, a mind, emotions. We are all born in the same way and we all die. All of us want happiness and do not want to suffer.

- the Dalai Lama XIV in The Art of Happiness: a Handbook for Living

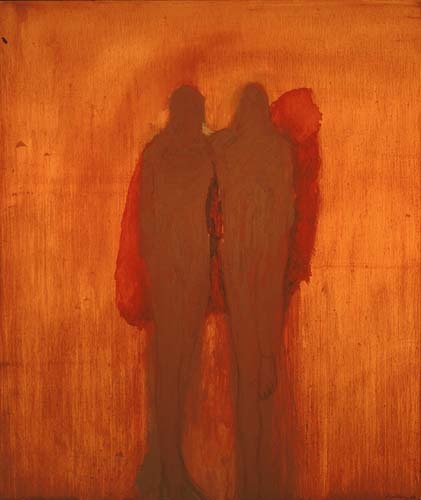

Couple with Red is an apolitical painting about how our humanity connects us and what we have in common. I'm going to characterize the approach of this painting as "Universal Humanism." It emanates an optimistic and utopian feeling of commonality. One of the essential elements of friendship -- and of a healthy society -- is the feeling of commonality.

When we as individuals feel excessive difference from others our social connections fracture and we retreat into smaller and smaller circles: I think of these metaphorical circles as "tribes" that keep us divided and create competition and conflict.

Yes, contemporary tribalism is a major problem -- just think about American politics and you will instantly know what I mean -- but commonality has its pitfalls too: hate groups can be built on themes of commonality.

Still, we all need friendship and we all need human connections. We can't survive or thrive as individuals or create any meaningful sense of identity without friends. In our polarized, fast-changing, aggressive society -- one in which the "self" is always being made insecure by consumerism -- personal identity is a fragile construction that needs to be defended and protected. Not surprisingly, identity is one of the leading themes of contemporary art.

In innumerable paintings, performances, videos, and installations, Postmodern artists concerned with identity have made political, sociological, cultural and personal points about the particularities of their situations. Gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity -- and other factors that have historically circumscribed, damaged and defined the lives of both groups and individuals -- are the raw material of Identity Art, which presents itself as being in opposition to hostile social and historical forces and contexts.

I am rather susceptible to Identity Art because it holds the possibility of broadening my understanding of others and increasing my empathy. I use art museums and galleries as my churches, and Identity Art -- when it works -- can be a kind of sermon that tells me how I might become a better person by understanding the situations of others. That is, of course, exactly what the artists who make Identity Art have in mind.

One artist who deals with identity in a way that speaks to me is Kerry James Marshall, whose works in many media have commented on race and black identity in a way that consistently strikes me as both authentic and aesthetically accomplished. Marshall, whose work is deeply rooted both in African-American history and his personal history has commented that: "You can't be born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955 and grow up in South Central [Los Angeles] near the Black Panthers headquarters, and not feel like you've got some kind of social responsibility." I buy that, and if I had the bucks I would buy his work too.

If you don't know Marshall's work take a few minutes to watch the video below and you will get a feeling of what his work looks like and where he is coming from.

Of course, not every artist who deals with identity is as accomplished or articulate as Kerry Marshall. And not all Identity Art is good art: not by a long-shot.

This brings me to one of the major problems with Identity Art: it can create a situation where really lame art seems to resist criticism because it stands for "good" progressive values. There is a great deal of Identity Art being made now that is shrill and contrived, but which gets a free pass from critics and curators because it presents its message as sacrosanct. As someone who writes about contemporary art I know that if I make critical comments about a work of art that deals with racism there is a chance I may be singled out as being racist, even if it is the aesthetics of the work that leave me cold. Identity art connects directly to hot-button social issues and that makes critical appraisals a real minefield.

Speaking of minefields, a recent blog posted by Ryan Wong on Hyperallergic -- I am Joe Scanlan -- caused a number of small explosions. In his blog Wong -- a curator and writer -- claims that he invented an artist by the name of Joe Scanlan who was carefully designed to "test the limits" of what he calls "straight white male positionality within in the art world." Joe Scanlan, as Wong tells the story, invented Donelle Woolford, a black female artist.

Amazingly -- or not amazingly, depending on how cynical you are about the New York art world -- Woolford's "work" was included in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Ryan Wong claims that he was surprised "how long it took for the Joe Scanlan/Donelle Woolford project to be identified as racist." Here is the kicker: Wong's blog was a parody that added another layer of commentary to something real. Joe Scanlan is in fact a real artist who really did invent Donelle Woolford and who really does teach art at Princeton.

There is a lot to discuss here, but for me one thing really stands out: I'm amazed that the work created by Scanlan for his invented artist Donelle Woolford actually made it into the Whitney. Woolford/Scanlan's contribution to the show included an off-site performance called Dick's Last Stand which "explores the central role given to the male sexual organ in both American art and politics." Isn't there anyone in New York with a sense of humor who immediately recognized that as parody, not art? Of course, I didn't recognize Wong's blog as a parody until it was pointed out to me.

While heads spin and comment wars rage over all of this actual artists are left dealing with serious moral and philosophical questions such as "what do I want my art to say about the human condition?" One way that artists in the western tradition used to make statements about humanity was through allegory: they created stories and figures that symbolize and stand for ideas about human life. There seems to be a resurgence of ambitious allegorical painting going on right now -- I think I need to write a full blog about that -- but I'm presenting Patricia Watwood's remarkable Sleeping Venus below to provide an example.

Patricia Watwood, Sleeping Venus, 2013, oil on canvas, 40" x 40"

In one sense Sleeping Venus is Identity Art: Watwood's allegorical image of the power of beauty as a tool of enlightenment has a hint of feminism about it. At the same time, it has something in common with the qualities that I admire in Nathan Oliveira's art. Sleeping Venus is a universal symbol of beauty, not a particular woman. If you have been looking at too much Identity Art -- or if you are determined to seek out every shred of political suggestion in every work of art -- you may see her as a privileged white woman.

When I look at works of art I am more interested than ever in a single question: "What do I have in common with the artist who made this?" Identity Art has its place -- although I do worry that in the wrong hands it can actually create divisiveness -- and I'm not going to say that we don't all need to know about the world's mis-alignments and injustices. Its just that at this point in my life I am so much more interested in what I have in common with others than in how we might be different.

Of course, I am a privileged white male, so maybe being able to approach art and people that way is my luxury. I'm always open to discussing that possibility...