I recently interviewed Margaret Bowland, and asked her about her background, and the ideas and values that vivify her art.

John Seed Interviews Margaret Bowland

I grew up in a North Carolina that no longer exists. Pre-internet, small towns were kingdoms. Burlington, NC, the town of my birth was totally self contained. We were taken as children to Greensboro, to Raleigh or Chapel Hill as my own children have experienced going to London or Paris. Books were my only link to a larger world. I found solace in knowing that others were asking the same questions that consumed me.

Everyone attended a church in my home town. As a small child I thought when an adult referred to "various religions" he or she was speaking of Protestant sects, Methodist, Baptist, etc. And I was taught to vaguely fear Catholicism. My family's social life was created by its submersion in family and the Baptist Church. From very early childhood I knew that there was something wrong with me.

Sitting in church, three times a week, I believed what others were telling me, that God was speaking to them. But I knew that He never spoke to me. I had no idea why. I prayed nightly and listened, straining in the dark, but there was only silence. So I began to lie about it. There were times in the life of a Baptist child in which you were expected to "testify" that Jesus was in your heart. I did as I was told, all the while knowing myself to be a fraud. This self knowledge, this great shame, created me.

When attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill I wavered for years between declaring a major in art or one in English lit. I decided to throw in my lot with the English department. I was in total despair within the art department. This finally led to my dropping out of college altogether.

I had arrived at Chapel Hill, which is just 30 minutes from my home town, like a kid today arrives in NY City from Iowa. Everything was dazzling, sophisticated, and terrifying. Here I believed, I would find the answers to so many of my questions. Here, I would be taught to paint like the great artists I had seen in books. But of course, I was walking into college in the early 70's and none of what I wished to learn was for offer in the art department of that time.

I was living in a time that celebrated "freedom." Yet, in the art department I found there to be one way and one way only. The teachers were all Abstract Expressionist men from Chicago. When I met them they had warily begun to move from Rothko to Frank Stella. The largest conversation was whether to let the lines you made on the canvas bleed or not; whether to leave the masking tape you were using to create those lines breathe a bit at their edges or fix them hard and fast with acrylic medium. I was told firmly there was no painting of the figure.

I entered a life drawing class where before us stood a naked young woman. Our instructor told us to "draw the fourth dimension." I was 17 years old. My despair and confusion shook me. I painted abstract paintings along with everyone else. I felt exactly like I had in the Baptist Church. I was back in a religion that held no answers for me, that dismissed my questions. Again I was a fraud. But the depression at times would flare up as anger.

I made the sculpture teacher a huge magnolia pod of felt that I sewed and affixed to a chicken wire base. I lined the pods with pink satin and he absolutely loved it. Each seed could be pulled from its own vagina of pink satin and pushed back within. The seeds were the size of a child's hand. His euphoria over the piece deeply confused me. I had liked making the pod. I liked replicating it. But these instincts I believed were relegated to just playing with crafts.

The works I had glimpsed in museums were getting further and further away. In the English department the big questions were being asked. How to deal with death without the solace of God? How to define meaning? Here I discovered many writers, among them James Baldwin. His life experience, coming as it did from such a rigid religious background was one I understood. This brilliant man was writing from exile. His doubts and downright disbelief were written there on the page.

Back in the art department, it felt to me there were no conversations of importance. Teachers wafted in and out of classes. often only staying for an hour of a three hour class. At critiques I was totally lost. I could fathom no continuity in the values and judgments of the teachers and they did not pretend to have one. Frankly, it broke my heart. So I ran.

Yes, I have spent my entire life as a "contrarian", but I never for one moment wished to be. I have sought all of my life to be in a community, to feel like others feel, think like they think. But as in a line said by a character in Saul Bellow's "Augie March". "The soul wants what the soul wants."

My parents could never understand why I could not believe in God as my college professors could not understand why I could not embrace their new religion of Abstract Expressionism. Now the current orthodoxy is Post Modernism and I have had the predictable results. I stand in line anxious to receive my glass of Kool-Aid but when it is in my hands I find that I cannot swallow, even though if I could, rewards might be mine.

Art in my life time has been as doctrinaire as any church I have ever encountered. There are things "one cannot do" and these seem to be the things to which I am attracted. I have been told by current artists that the very way that I paint marks me as unsophisticated, backward. One can paint the figure now, but only in a somewhat careless way, or in a cartoon-like format. It reminds me of the humor of Wes Anderson, Bill Murray. You can tell the story but only insofar as you are signaling to us that you are simultaneously aware that storytelling is an ironic exercise.

The paintings I make are what come to me. They are born of my searching through this world for a belief system. I paint what my psyche tells me to paint and what my eye perceives to be beautiful. I am not coy and I realize, profoundly, that this is a problem for many artists in these times.

I have made that statement. A more accurate statement would be that beauty makes sense to me when it has suffered damage -- therefore entering the world -- yet has held on to a sense of itself. That is a shocking accomplishment in a world that distrusts all shared beliefs. Beauty no longer exists as an ideal. The word has fallen to the level of a description of pretty girls and boys attired in expensive clothes.

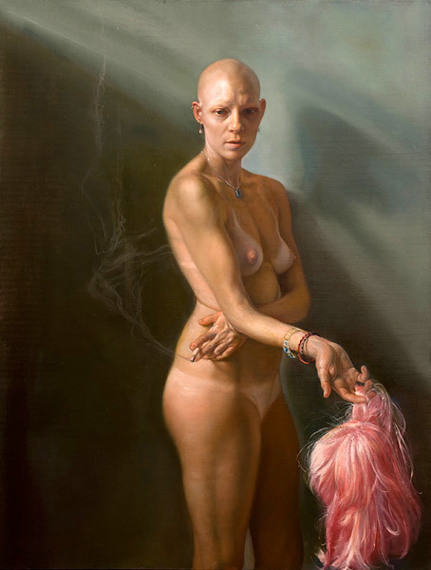

I look at a model I have used for years, Klare Potter. She is a preposterously beautiful woman by any standards. Fair, long legged, tall, perfectly proportioned. But an extreme case of Alopecia has left her with no hair on her body at all. In the Metropolitan Museum of Art I saw a statue of the goddess Isis. She also had no hair. The Egyptian royalty are thought to have suffered from hair loss as a side effect of inbreeding. Looking at Isis, covered in white paint over the terra cotta, I saw Klare. I covered her in white paint and placed her in a bath tub.

How and why did you begin your "Anna" series?

I began the "Anna" series like I have every series in my life, by meeting the model. Anna appeared one day at the bus stop on the corner of my street and I asked her if she would model for me and she said yes. Our lives then began to entwine. I have been out in the world with her, at restaurants and bars. I am 5 feet 10. So the two of us get our share of glances. Anna always acts as if she does not notice. But when we are alone I have heard stories, of course. Anna lives defiantly. She has suffered extensively by existing outside the norm, but she has triumphed.

Now we look at historical portraiture and see within it only the trappings of the rich and powerful. As modern artists we rummage through these trappings and symbols as through a sack of old costumes. We see in the paintings of Van Dyck, the imperial victory of capitalism and we walk away. We know better. Capitalism has been found out. It is both the monster and the master.

But what of the beauty within a Van Dyck? What of the validation, of the immortality that Van Dyck bestowed upon his subjects? You stand before his paintings of golden haired brothers, attired in satins and read below that both were killed in battle just after the painting was completed. You think of their final scene, of the mud and the blood. Yet that reality does not render the portrait before you a sham. Both are true. Anna wanted to live within this paradox. She wanted to feel that lifting off. She wanted to stand before a painting done by me of her and see herself through my eyes and as such, through the eyes of the world. She wanted to exist apart as art allows one to do.

Yes, I have often been told this; but rarely by African Americans. And this taboo certainly does not hold true in other art forms. For decades white authors and film makers have made films and written books about African Americans.

I feel I have the right to paint African Americans because out history is combined. I grew up in a segregated South. I grew up in a world of signs on doors and water fountains that said "White and "Colored." Children know in their bones when they are in the midst of injustice. They experience the nausea that comes from the realization that the adults are not to be trusted. They grow up in a world of shame from which there is no departing.

Again, in a quote from Saul Bellow, I see the facts of this. He says "Repression is not precise. You repress one thing; you repress the thing adjacent". The white adults who raised me had no idea of what they were paying through the repression of their souls by the world order in which they lived. But damage was done.

The inclusions of more voices in art has certainly been a wonderful thing. As a woman, I am one of the voices that were not heard in the past. All of my life people have approached me and declared, "You paint like a man!". And all of my life I have flinched but realized that this, from the speaker, had been meant as the highest compliment. It is the obvious and correct statement, after all, to ascribe to a painter who has spent her entire life looking and trying to learn how to paint from men. I never thought of it in that way, not once. I simply wanted to learn what they had known so that I could try to create my own worlds as had they.

I find it depressing when artists who are not white males say that they have nothing to learn from these old dead guys. Well, there is an inherent problem here. The very language they speak, the images they see, have for the most part been created by males. Throwing away the accomplishments of these men is not possible. If you are a feminist film maker you are using machinery created by men and the very concepts you are employing to tell the story were created by men.

"Isms" are not my thing, There is always at the heart of any political act a simplifying a cutting away of the very details I find most interesting. Often political units feel to me like desperate attempts to find a center again, but sadly, this center is not one of intellectual unity but only a grab for power. I do not see change, only the replacing of one despot by another.

I teach at The New York Academy of Art in NY. It is solely a graduate school so the students we have are facing the hard facts of the market place upon graduation. In the hall I heard two of my students discussing a third. They said, exasperated, "How can we be expected to compete with her? She was born poor, if white, in a trailer in NC. She was raised by a single mother after her father became mentally ill." What stunned me was that the student to which they were referring was indeed a threat to them. She was one of the most talented students that I had ever had, but her work was never even mentioned. It was her story that frightened them. The personal story has often now become the Art. Art is not about creating something. It has become a lifestyle choice. One decides to be an artist and then whatever follows is art.

There are many artists whose work places them way above the pettiness of these facts. I was teaching from the art of Mickalene Thomas one day. I had showed images of hers to show the students about the ways space could be manipulated in the hands of a great artist. Thomas had led us into a perspectival space only to leave us circling back upon ourselves like in De Chirico. Unlike his nightmare colors of greys and browns, Thomas had lit her world with lime green and pink. She had scored her moldings with glitter. All to show us that what we believe we can enter we cannot. She shows us how easily we can be seduced by gorgeous color into entering a world that wakes us up. The class and I talked about this work, brought in paintings of Giotto to compare; we talked for nearly an hour.

Mickalene Thomas is an African American lesbian. But not once were these facts necessary in the discussion of her work.

Of course a backstory is of use in the understanding of an artist's work. But it should be small potatoes by comparison to the work itself. After all, the work presumably will one day leave home and have a life of its own without mom or dad. Or that remains my hope.

Margaret Bowland: They Say It's Wonderful

November 14, 2014 - January 16, 2015

Alan Avery Art Company

315 East Paces Ferry Road

Atlanta, Georgia 30305