A Brief Rant on the Exhaustion of the Avant-Garde, Zombie Formalism and What Contemporary Painting Needs to Move Forward

"...Try to explain to Monsieur Renoir that a woman's torso is not a mass of decomposing flesh with those purplish-green stains."

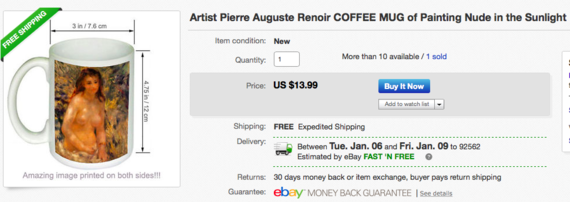

- Critic Albert Wolff, writing about Renoir's Nude in the SunHard to believe, isn't it, but Renoir's Nude in the Sun was once considered threatening: when first exhibited it's Impressionist palette violated long-standing academic rules about the use of color in shadows. These days you won't find a museum director anywhere in the world who wouldn't covet the tiny, sun-dappled nude, and the once offensive image is emblazoned on a coffee mug that can be purchased on eBay for $13.99 with free shipping. Now that its original aura of challenge and disruption has dissipated, a work of art that was once cutting-edge has now entered another category: it is a certified and fully commoditized masterpiece. Nude in the Sun should be considered "formerly avant-garde" as the cultural shock that it once evoked was exhausted years, even generations, ago.

Now, 140 years after Wolff derided it, Nude in the Sun resides in another kind of cultural institution, the Musée d'Orsay, and the tables are turned. Modern art and its children -- Postmodern and Contemporary Art -- are the "Academy" of our time, and the tradition of the avant-garde has been elevated and enshrined to the point that you might even say that it has been embalmed. The values of the avant-garde, including individualism, experimentation and progress, are now sacrosanct, and the boards of Modern and Contemporary art museums in the United States are populated by the nation's wealthiest, most culturally elite citizens. They serve the same conservative role that titled aristocrats played in the European academies of the past: they are guardians of the dominant culture.

This creates real problems, as truly avant-garde works of art need the tension created by opposing cultural values and institutions to sustain their meanings and put them in relief. When too many people come to embrace avant-garde works and styles, their intended purposes and meanings wilt and die quickly. As a biologist will tell you, things grow best when subjected to the right stresses, and culture is the same way. Healthy values -- including social, political and cultural values -- need constant challenge and revision to remain fresh, and it strikes me that the spirit of the avant-garde in art is exhausted and complacent: Its "progressive" values have become de rigueur. If you see the words "pushes the boundaries of..." in an art review, you have encountered a critical blandishment that has become a cliché, ready to be retired.

Realism, one of the related forms of painting that would have been acceptable to the members of European Academies, has been consistently relegated to the sidelines. As artist Eric Fischl noted in a 2009 interview, "There's always been realist painting. The avant-garde ignores 99 per cent of it."

Compared with realism, the broader field of representational painting has done a bit better in finding its place in the avant-garde: I'll be bold and say that only 98 percent of it gets ignored. Generally speaking, the representational art that makes its way into the mid and upper ranks of the contemporary art field has to be credentialed as avant-garde in some fashion. "Outsider" status can work, as can a reliance on subject matter that is "deconstructed" in relation to social, sexual and political issues. Self-conscious strangeness, obsessiveness, and irony can "credential" representation, and so can Warholian strategies involving mechanical and technological methods of image making. Conceptualism, which I think tends mixes with representation very lamely, can also get you in the front door of the avant-garde academy. Sadly, a connection to wealth and/or celebrity can work too.

For representational painters whose work does fall into one of the categories above there are pitfalls to be avoided. For example, painter Bo Bartlett believes that "To be earnest is the greatest taboo in contemporary art." Any representations of conventional beauty that don't have a dose of nihilism mixed in are excluded from the avant-garde as "kitsch," but self-conscious super-kitsch is a hot ticket.

If I haven't transcribed the current rules and perimeters of acceptable avant-garde representation perfectly, I apologize: they aren't written down in a handbook anywhere, but they definitely exist. I also doubt that the French Academy had a manual forbidding purplish-green shadows on human skin, but Albert Wolff knew the rules and limits of his era's academy regardless. When a cultural system has ossified and become fragile, knowing the rules is especially important, and both artists and critics need to pay close attention. In New York right now, the matrix of unspoken rules has resulted in a vogue of abstract and semi-abstract paintings by young artists that play it safe by saying very little, but sell well. Critic Walter Robinson, who first noted the "reductive, straightforward, essentialist..." urges present in this new school of painting, gave it a grim, clever name that has stuck: Zombie Formalism.

Peter Schjeldahl, the art critic for the New Yorker, has been looking over this new genre of offhandedly abstract painting, and in his recent review of The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World, he observes that the young painters represented use "tactics" which "include emphases on gritty materiality and refusals of comforting representation." He also notes that the "joys" of the works on view come "freighted with rankling self-consciousness or, here and there, a nonchalance that verges on contempt." The "joy" he describes sounds very circumscribed indeed, especially for a show presented at MOMA, the original temple of America's avant-garde.

The "nonchalance" that Schjeldahl notes apparently exists in a void that critic Andrew Sullivan believes has been created in an art world "bubble" inflated by "flipping" and the transformation of avant-garde works of art into bankable financial instruments. In a year-end commentary titled Where Does 2014 Leave the Art World, critic Goldstein derides Zombie Formalism complaining that: "The intellectual content that allowed previous developments in painting--gestural abstraction, process-driven minimalism, et cetera--to break new artistic ground is voided, leaving a colorful corpse so devoid of ideas one could imagine it craving human brains." Is it just me, or does Sullivan's use of the phrase "colorful corpse" sound a bit like Wolff's complaints over Renoir's "mass of decomposing flesh with those purplish-green stains"?

The situations that both critics describe -- even though their tone differs somewhat -- strike me as symptomatic of avant-garde exhaustion: Zombie Formalism is an ironic, self-conscious artistic response to a situation in which academic rules have choked off the oxygen painting needs to breathe. And yes, it is also a tiny over-commoditized avant-garde zone supported by speculators. Andrew Goldstein thinks the movement is short of "intellectual content" and "ideas," but I see it a bit differently.

If the situation I have outlined sounds distressing -- and in many ways it is -- it is also a moment when change seems imminent. There are many fantastic artists out there making significant work, ready to burst onto the scene when change blossoms. There have never been more institutions dedicated to contemporary art or more money available to be spent on it, and that is a good thing. The problem is that the definition of avant-garde needs to be revised to encompass and include art and artists that are brave enough the reach backwards and forwards at the same time. The avant-garde of the future needs to feed itself with hybridization, consolidation and assimilation.

I think that painting has to look back over its shoulder to realist and academic painting before the Salon des Refusés; in fact, it can and should go all the way back to Lascaux if it needs to. I see the history of painting as a very long line with no beginning and no end. Culture has certainly created moments and movements in painting -- most recently we have called them "isms" -- and living in a media age artists can have access to all of them, although not always on a first-hand basis. I like what the painter Jean Hélion said: "All the 'Isms' seem to me to be facets of a whole that should be painting."

There is a deep need for art that is authentic, engaged with the world and more about skill and knowledge than ego. Representation, which has been so restricted for the past decade, has vast untapped potential, and can be "progressive" in countless unexpected ways. As I commented in my review of The Figure: Painting Drawing and Sculpture, Contemporary Perspective, "contemporary representation is coming on strong," and I think that schools like the New York Academy, which equip students with a strong base of traditional skills, are equipping a generation of artists who will re-invigorate and re-define the avant-garde.

I would like to think that zombie formalism is the end-point of one kind of thinking about painting; as "isms" go, I predict it will be a blip. Peter Schjeldahl believes that "painting has lost symbolic force and function in a culture of promiscuous knowledge and glutting information," but I think he is wrong. As Renoir knew, when painting finds a way to resist rigid culturally imposed rules, it can persist, become relevant again and thrive.