A few years ago I was standing in a Malibu furniture store looking at coffee tables when I heard another shopper whisper excitedly to a friend:

"Hey, isn't that Bruce Willis? He looks just like he does in the movies... but maybe just a bit shorter."

I can confirm: it was Bruce Willis, and that was one hell of a nice Ferrari he was driving. He didn't look short to me, but I digress.

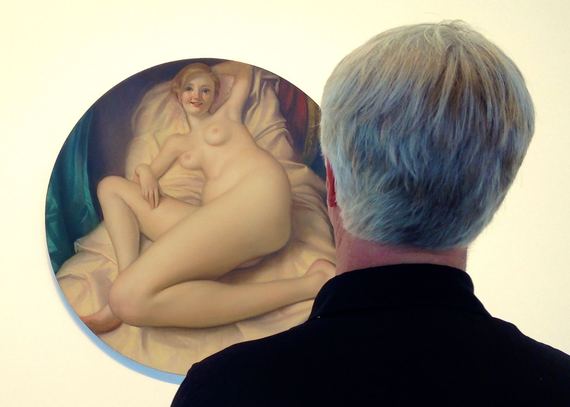

The author looks over John Currin's Reclining Nude: Photo by Matthew Couper

While viewing the recent John Currin exhibition last month at Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills, I found myself saying some rather similar things to my friends Matthew Couper and Jo Russ, who were touring the show with me. Currin's paintings were already well known to me, but only in the form of photos in magazines and jpeg images seen on the net, and I assessed them just the way that the woman in Malibu had assessed Bruce Willis:

"They are a bit more painterly when seen in person," I told Matthew, "and the canvas is a bit rougher than I expected."

Of course, considered in the context of today's media-driven art market, these observations are inconsequential. Everything in the show was already sold -- for $2 million plus each, or so I am told -- and Currin's reputation as an art world star is well established. The feeling I had looking over Currin's work was that the paintings themselves were celebrities, glamorized by the fame of the artist who made them and their high market values. That isn't an original idea: I think it was Robert Hughes who more than 30 years ago said something along the lines that "Paintings are now celebrities and museums are their limousines."

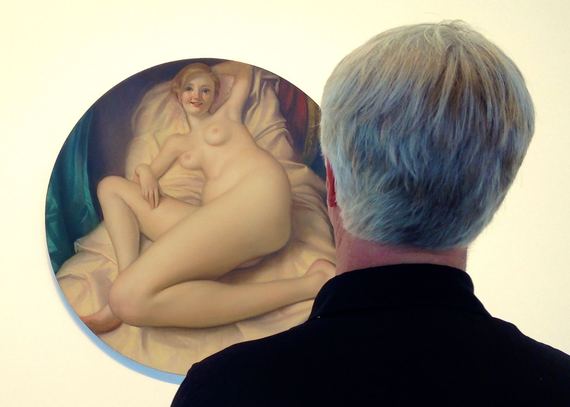

Selfie Takers in the Van Gogh Museum. Photo by Becca Burns

Hughes was prescient in his observation and the recent phenomenon of museum selfies drives his point home very nicely. Being in the presence of a famous painting seems to be replacing -- especially for younger art viewers -- the experience of closely inspecting works of art. If you are interested in scrutinizing the surfaces of works of art slowly and scrupulously you are a connoisseur or possibly an artist with a kind of professional vested interest in a given painting's construction.

A case in point: when a number of my artist friends visited Kehinde Wiley's exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum recently, they had a lot to say on Facebook about how Wiley's paintings looked to the naked eye. There was quite a bit said about what Wiley's assistants in China had painted (the patterned backgrounds) and what he had painted himself (the faces) and also some comments about the fact that Wiley's technique was gradually becoming more confident.

I enjoyed hearing their first person observations, but also realized that they were having a similar experience to the one I had at the Currin show. Wiley has become famous because of the social messages of his artwork, especially his bold imagery of African-American men presented in a context largely borrowed from the grand traditions of European portraiture. What I and my other "painting geek" friends observe about his work in person isn't going to affect his career trajectory at this point. Like Currin, Wiley has created a body of work that transmits its messages well in magazines and on the net, and that aspect of his work is very potent -- and possibly essential -- at this moment in time.

In a media society the reputations of painters are made in magazines and on the web. Seeing surfaces in person is a luxury and an afterthought. A recent survey indicates that over 50 percent of contemporary art collectors have now purchased art on Instagram. There is clearly growing confidence among collectors that digital images can tell you enough about a work of art to spend big bucks. When the crate arrives, they can look over their purchases the way I looked over John Currin's paintings on the gallery wall, and make a few discerning comments if they are so inclined.

If you have an "eye for art" and a keen interest in inspecting the surface of works of art, both out of curiosity and a quest for deeper meaning, your abilities are linked to an increasingly outdated notion of connoisseurship. Having an "ear" for art -- which means that you pay attention to what people are saying about what is hot on the market -- is now the best way keep up with the trends. Maybe all of this has something to do with why art critics, who have been traditionally been relied upon to carefully scrutinize works of art and make critical pronouncements, seem increasingly impotent and irrelevant. When the editors of Hyperallergic suggested at the end of year that art critics might as well be replaced by Instagram, they made a very funny and rather relevant point.

When I can manage to pry myself away from my laptop and make the grueling drive into the city I always make time to see art in person. That said, I'm increasingly realizing that looking at art on the web is the only way I can really keep abreast of what is happening in my field. I'm still dedicated to the idea of connoisseurship, even in an age when visual ideas transmitted with immediacy are in the forefront. It's still great to visit museums and take things in slowly, inspecting the surfaces.

In L.A. there is also the chance I will see some celebrities, as they seem to frequent art museums. One of my students returned from a field trip recently and told me that she saw Tom Hanks at the Huntington. She said he looked just like he does in the movies, but a bit older now.

"Hey, isn't that Bruce Willis? He looks just like he does in the movies... but maybe just a bit shorter."

I can confirm: it was Bruce Willis, and that was one hell of a nice Ferrari he was driving. He didn't look short to me, but I digress.

"They are a bit more painterly when seen in person," I told Matthew, "and the canvas is a bit rougher than I expected."

Of course, considered in the context of today's media-driven art market, these observations are inconsequential. Everything in the show was already sold -- for $2 million plus each, or so I am told -- and Currin's reputation as an art world star is well established. The feeling I had looking over Currin's work was that the paintings themselves were celebrities, glamorized by the fame of the artist who made them and their high market values. That isn't an original idea: I think it was Robert Hughes who more than 30 years ago said something along the lines that "Paintings are now celebrities and museums are their limousines."

A case in point: when a number of my artist friends visited Kehinde Wiley's exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum recently, they had a lot to say on Facebook about how Wiley's paintings looked to the naked eye. There was quite a bit said about what Wiley's assistants in China had painted (the patterned backgrounds) and what he had painted himself (the faces) and also some comments about the fact that Wiley's technique was gradually becoming more confident.

I enjoyed hearing their first person observations, but also realized that they were having a similar experience to the one I had at the Currin show. Wiley has become famous because of the social messages of his artwork, especially his bold imagery of African-American men presented in a context largely borrowed from the grand traditions of European portraiture. What I and my other "painting geek" friends observe about his work in person isn't going to affect his career trajectory at this point. Like Currin, Wiley has created a body of work that transmits its messages well in magazines and on the net, and that aspect of his work is very potent -- and possibly essential -- at this moment in time.

In a media society the reputations of painters are made in magazines and on the web. Seeing surfaces in person is a luxury and an afterthought. A recent survey indicates that over 50 percent of contemporary art collectors have now purchased art on Instagram. There is clearly growing confidence among collectors that digital images can tell you enough about a work of art to spend big bucks. When the crate arrives, they can look over their purchases the way I looked over John Currin's paintings on the gallery wall, and make a few discerning comments if they are so inclined.

If you have an "eye for art" and a keen interest in inspecting the surface of works of art, both out of curiosity and a quest for deeper meaning, your abilities are linked to an increasingly outdated notion of connoisseurship. Having an "ear" for art -- which means that you pay attention to what people are saying about what is hot on the market -- is now the best way keep up with the trends. Maybe all of this has something to do with why art critics, who have been traditionally been relied upon to carefully scrutinize works of art and make critical pronouncements, seem increasingly impotent and irrelevant. When the editors of Hyperallergic suggested at the end of year that art critics might as well be replaced by Instagram, they made a very funny and rather relevant point.

When I can manage to pry myself away from my laptop and make the grueling drive into the city I always make time to see art in person. That said, I'm increasingly realizing that looking at art on the web is the only way I can really keep abreast of what is happening in my field. I'm still dedicated to the idea of connoisseurship, even in an age when visual ideas transmitted with immediacy are in the forefront. It's still great to visit museums and take things in slowly, inspecting the surfaces.

In L.A. there is also the chance I will see some celebrities, as they seem to frequent art museums. One of my students returned from a field trip recently and told me that she saw Tom Hanks at the Huntington. She said he looked just like he does in the movies, but a bit older now.