John Seed Interviews Melanie Daniel:

I grew up in a city called Kelowna, British Columbia, nestled in a beautiful valley of forests, lakes and orchards. It is extremely arid and blazingly hot in the summer (up to 40 °C) and then winter inevitably comes and outdoor life continues on the ski slopes or in the gentler woods for snow-shoeing and tobogganing. My younger sister and brother and I were always outdoors in all seasons hunting for critters and frogs, fishing in the creeks or excavating clay from the cliffs behind our grandparents' house. We returned daily to our childhood haunts where only kids went, a parallel universe for us and our posse.

Those were different times, I realize now, and we were never supervised. Free to roam, we invented games, dares, bizarre rituals, and protocol for deep forest sport. The neighborhood creek, an all-season kid headquarters, also served as the final resting place for countless pet gerbils and lizards. At sunset, our deceased beloved pets were regularly sent downstream on blazing Viking ships improvised with popsicle sticks. On less somber occasions, being the avid pyromaniacs that we were, more than once we watched from a safe distance as the local firefighters extinguished the contraband Playboys that had started it all. My brother and his nervous friends would frequently incinerate their forbidden erotic stash once discovered by us, their older sisters, the killjoys.

Although we would have happily watched endless hours of TV sitcoms and cartoons, my parents were frequently heard saying, "shut that thing off and go outside", which we grudgingly did. But "outside" never disappointed. It was always a place to escape into and to be happy. The dead silence of snow, the smell of cut grass, the deafening drone of cicadas in afternoons and the melancholy return of autumn and the dreaded classroom - the reliable cycle of my formative years in Canada. It has never left me.

Love brought me to this place. Not adventure and certainly not ideology. In the early '90's I travelled through India and one day I set my eyes upon a curly haired, dark stranger. I was sure he was Italian. I knew nothing of Israelis. After a while, each returned to his respective country and only many months later did we commence a slow correspondence through posted letters. Email was not yet widely available. Rather impulsively, I dropped my final year of university studies in history and philosophy and boarded a plane for Israel, certain that I would be greeted by a swollen silver moon over Jerusalem. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Jerusalem was a rough city, its denizens crustier still. I returned briefly to Canada to make some money tree-planting and ultimately to figure out what to do about this man. Eventually I did return to Jerusalem, and I knew that my success or failure would depend less on matters of the heart and more about what I would do there.

Soon after my arrival, the prime minister was assassinated, later the second Intifada was unleashed, and all hell broke loose. It lasted five years and it changed everyone, deeply. Perennial engagement with mortality is humbling. I live in constant proof of the fragility of life and it's something that follows me everywhere. And although I don't believe that this knowledge gives me any advantages in life it has sharpened a keen regard I've always held for the present tense and a solid respect for the material/natural world. Communion with nature has always been enough for me and requires no further pontificating from men with snowy beards.

The culture shock I experienced here was an ongoing hiccup, lasting years. Israelis are without a doubt the most tactless humans on earth but this abrasive quality has a very important flip side. They also happen to be the most generous, candid, creative and humorous people I have ever met. I have learned much from my Israeli friends. The other culture shock was Israel's natural landscape, the desert and its open unforgiving sky. I recoiled at my first encounter with the desert; I felt I had no where to hide. It took me many years to embrace this existential landscape as it was nothing like the towering pine giants that protected me in my youth.

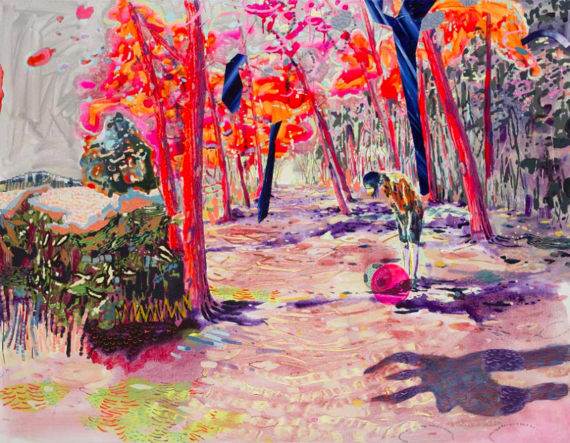

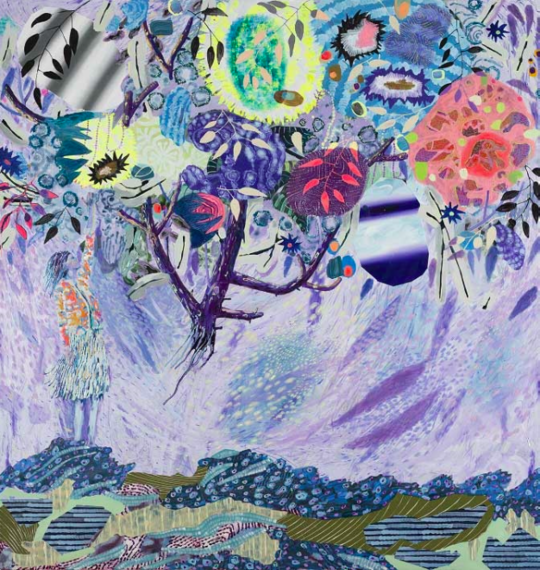

Yes, I think so. Even at school I was painting when the craft was decidedly unpopular and to the dismay of my instructors, I was also bent on weaving impenetrable stories into the work. For me, the paintings invent the places and characters, not the other way around. My paintings are so much about physicality which despite their reliance on narrative are still somehow resistant to language, interpretation, or even memory. I hope to induce a sense of dislocation by being both strange and recognizable. By keeping the narrative dreamlike and just beyond reach, I let the viewer bring something of their own to the painting. The narrative can unfold once the sense of familiarity recedes from the encounter, those scenes familiar to us through the landscape genre. My art is anti-nostalgic because I don't try rehashing actual experiences but invent them at the edge of my perception.

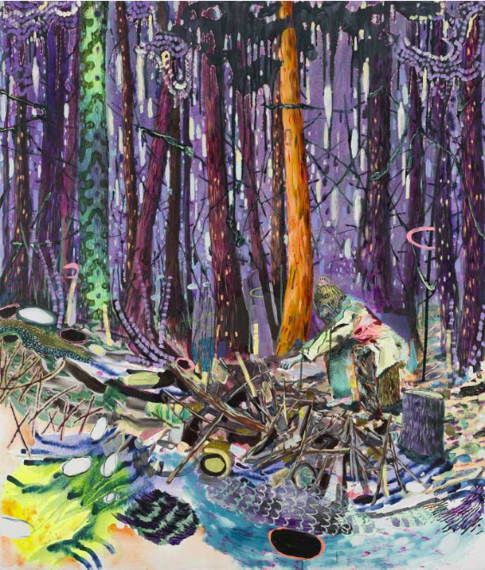

One piece, Scruffy's Emerald Secret is a favorite of mine. It's moodier that the others and I can identify with the bare-footed loner sitting on a tree stump, hunched over his campfire. Behind him looms this tall green patterned tree, a beautiful freak specimen. It shouldn't be there, but it is. The man shouldn't be there, but he is. Where is his family? Why is he alone in keeping vigil over this odd tree? This piece is one of several in a group I call Piecemaker in which I incorporate conflicting cultural motifs, embedded traditional Arabic patterns in a Canadian landscape. They can't be fused and remain irreconcilable. Not unlike quilt-making I "stitch" together disparate symbolic forms and patterns from both of these worlds which have become part of me.

One of the conditions of my decision to remain here depended on my ability to carve out a corner for myself, professionally. Making art and functioning competitively in that arena was a necessity for happiness and my own sanity. I started from zero and got a very good education and training in the arts. Self discipline was already established from my previous five years at Canadian universities, and I was very sure about how I wanted things to play out. Unlike many immigrants who arrive as adults, I had a huge advantage: art school was a big lingering bear hug. All of my friends, my political views, professional networks, and direct access to Israel's cultural carotid artery were all gifted to me during those years. I would not have survived here without it.

My family is the heart of my life, always. Everything else falls into descending order after that. I like being outside as much as possible. As a family, we do a lot of hiking and swimming, and picnics with friends. I live a street away from the Mediterranean Sea and need to see it daily. Most days are started with a run along the sea to stave off cabin fever in my studio. I'm an avid gardener and a member of a community garden and often get my son's kindergarten involved with horticulture. It's important for kids to understand where food comes from and to really see how we're all part of a shared life cycle. They also get a real sense of pride and ownership from their hard work. I read a lot, everything from Annie Proulx to Walter Mosley, mostly at night when everyone is asleep. Music, nonstop, but that's when I'm painting.

Who are some artists who have directly influenced your work?

Daniel Richter: he's the best living painter as far as I'm concerned. I can look at as his works for hours and they just keep unfolding. Violent and absurd, apocalyptic.

Peter Doig: a constant source of inspiration.

Cecily Brown: fleshy, carnal paintings that just disintegrate and then re-galvanize, pulsing. They take time to get into and you can't hurry them. This is one of the things what makes any good painting last. Brown overdoes everything, pushes the painting to the brink and I love that.

Mark Bradford: layer by layer, he builds up a thick-skinned topography from cultural detritus. It's like he maps out these strange mute neighborhoods replete with their own secrets and you want to scrape down to get to them.

Velazquez: bold mark-making and outbursts of sensuality erupting through thick globs of paint. He didn't want a smooth porcelain finish but rather wanted to show us the true corporeal surface of paint. For me, moving paint around is a steady point of fascination and Velazquez always delivers the goods in that regard.

Dana Schutz: she's madly prolific, restless, ballsy, and brilliant. I hit a wall over ten years ago and discovered Dana's work. It was like rocket fuel for me.

David Lynch: His scenes are permanently lodged in my brain. An unapologetic storyteller of storytelling.

Sally Mann: raw, haunting and achingly personal.

Kwakiutl and Haida art and myths: I grew up with the imagery and stories of First Nations peoples of the Pacific Northwest. Masks and totems and legends are always with me even if they don't find immediate expression in what I do.

PK Page: Canadian poet. Her vivid descriptions of fleeting moments of life hang in the air when I'm working. I just have to reach up and grab them. Here's a title: "Deaf-Mute in the Pear Tree."

James Ensor - He literally attacked his canvases with violent gusto, making these taut, weird and nightmarish scenes. Totally unsettling.

Melanie Daniel: Piecemaker

Shulamit Gallery

17 North Venice Blvd.

Venice, CA 90291

May 21-June 27, 2015