Here is a true story for you:

A few years ago a young artist from Europe walked into an upscale Los Angeles gallery. He carried with him a portfolio of his recent work, including a number of smaller paintings that he had put tremendous effort into. When he showed the gallery director his work it seemed to go well: there were murmurs of approval and meaningful glances.

Then, the gallery director asked a much-anticipated question: "How much do you want for these?" The artist responded without hesitation. "I need to get about $1,000 each for them, so I expect you could sell them for about twice that amount."

The conversation came to an immediate halt. "Hmmm..." said the gallery director; "Come back in a a few years when you are getting some higher prices for your work."

Yes: that happened.

Here is what this anecdote says to me. The problem wasn't the art, as the gallery director clearly liked it, but rather that the artist didn't price his art high enough. It seems counter-intuitive, doesn't it? Yet the gallery director made the right call, as he knew his clientele well and understood that low prices would put them off.

Rich people need to feel rich when the collect and they need more breathtaking "price points" to feel their affluence when they choose art. Add to that, art dealers have to pay the rent, and they like high priced art too. One of the reasons that more and more art dealers are interested in re-selling blue chip works is that a single transaction might bring them ten times the profit of selling work by an emerging and lesser-known artist.

Art is a luxury, not a necessity, and when it hangs on your wall part of what it is meant to broadcast is that you can afford fine, expensive things. The comedian Steven Martin apparently understood this and parodied it very nicely when he put price stickers on all the art that hung on the walls of his first apartment. If you are a serious collector, you don't want to be seen as what one former curator for a local billionaire once characterized in an interview as "Another fucking Jaguar driving dentist from Encino."

Welcome to the wacky world of art pricing where the word "bargain" can curse a sale and an artist's reputation. Whether you are a collector or a collector/speculator you are going to respond to the enticing idea that an artist's prices are moving up, not down. You don't want to stand in your living room explaining that "I love my Rolf Smeldley painting: I got it just as his reputation and prices were tanking." Upward marching prices are erotic while declining ones are just sad.

If Picasso paintings from the 1950s are now going for $179 million a pop, that makes you want one even more, right? When it comes to luxury items conspicuous consumption rules and bargains are for mall shoppers. As a collector, you want to generate envy among your peers, and buying relatively inexpensive works is unlikely to do that as only connoisseurs will appreciate your taste. Money, on the other hand, is a universal language that everyone understands. What many don't understand is that art and money have some strange chemistry together.

Think about this: if you don't have taste, but you do have money, art can hide your deficiencies. Expensive art flatters those who have the "wisdom" to shell out for it. You are always going to look "smart" when you what you have bought keeps going up in value.

We all learned the laws of supply and demand in Econ 101--the law of demand states that the quantity of a good demanded falls as the price rises--but the art world defies this maxim. Andy Warhol, Thomas Kinkade and other sharp artist/businessmen understood this and they upped production knowing that the more walls their work was seen on, the more demand would rise. They also kept moving up their prices as they moved up their production, and both died wealthy men. If you can make yourself into a brand in a capitalist society, you can sell lots of art and move your prices up at the same time.

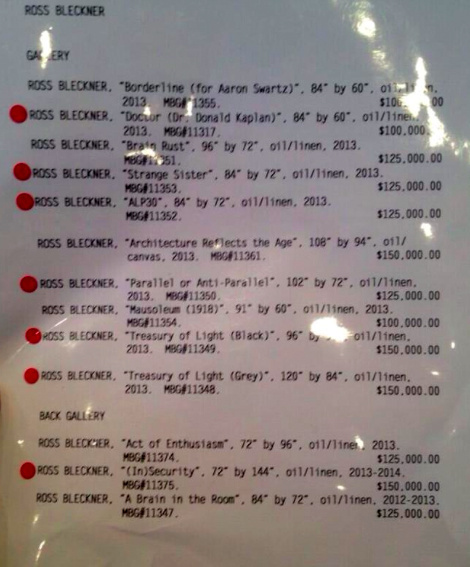

In the gallery world, the emblem of "success" is the posted price list, stickered with red dots. Who knows how many of these prices and dots are real--dealers have been known to fudge the results a bit to heat up the market--but doesn't this price list for the works of Ross Blackener, posted at the Mary Boone gallery two years ago, stir up feelings of envy and competitiveness? If people are lining up to pay six-figure prices for Ross Bleckner's work it must be good, right? Assumptions like that hold up the foundations all art transactions, as art has no real practical value. if your family was starving you would trade your Rembrandt for a ham sandwich to feed them... at least I hope you would.

Until that happens, I say move your prices up. It's a shell game, I know, but it apparently works. If you find this advice cynical, keep in mind that if you are a modest person who doesn't brag about what you do and who is embarrassed by the idea of over-charging for what you do, you may actually deserve a raise. If the art world hasn't seemed to "value" you are your work enough in the past few years, you may need to tease it a bit.