A sensitive, imaginative artist who has struggled both to make sense of and also to redeem her Southern Baptist upbringing, Bowland sees is fascinated by the idea of "damaged beauty." To create images exist apart from life's struggles -- while illuminating human vulnerability in the context of society and history -- Bowland works with carefully chosen models. Bowland's models are in a sense collaborators, providing the grace and humanity needed to center and anchor her stormy canvases.

In order to better understand the paintings on view in Bowland's current exhibition, Power, I recently interviewed Bowland and four of her models to understand how they work together.

Margaret Bowland

At the outset of this I want to say that I work both from live models and from photographs. When I begin with a model many photos are taken. After looking though these photos I develop ideas. Then the work begins, often from the photos themselves. Of course, this is never enough and the models must be brought back in. I set up clothes often on mannequins I have acquired over the years. Sometimes I build mannequins from all kinds of things, from chicken wire and paper towels, even old dolls.

I am drawn to the tangle of life, the beauty and the grace I find in people who struggle but cannot finally be annihilated. I place my beloved characters in a world I create that reveals the particular struggle of his or her life and then I watch while the very truth of each of them rises to meet me or anyone else who cares to look back. The word "collaboration" is the best one to use for the way that my paintings are developed. But the collaboration is of an odd sort. The person being painted doesn't sit down with me and discuss his or her conceptions of the work. It begins by my fixation on a particular person.

I first met Margaret five years ago at the Brooklyn Museum at a hosted event on the topic of building a collection of African American art. We were both in the audience and during the panel discussion I made a statement, then asked a question. Margaret was intrigued and we spoke. As an independent curator, I had attended the event out of curiosity, but didn't know who Margaret was when I met her and hadn't seen her work before meeting her. When I then visited her home, I realized she was one of the best painters I had ever met.

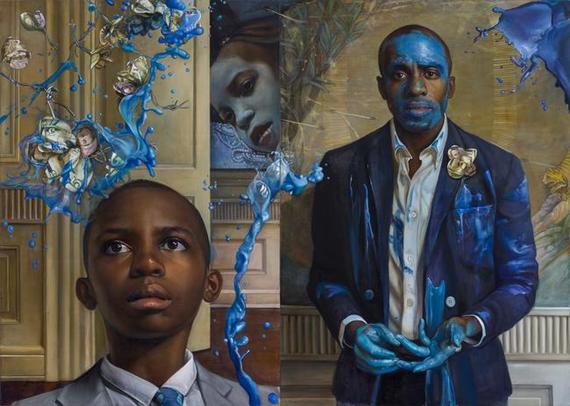

As our friendship developed, I never even considered having Margaret paint me: I try to stay at bit objective in my relationships with artists. About five years after we met Margaret asked if I would be in a painting along with my son Dylan. I knew her history of painting young people and trusted that she would be respectful and mindful, so I had no issues saying "yes." I knew she could tell a different kind of story with a father and son, as Margaret has mainly painted women before.

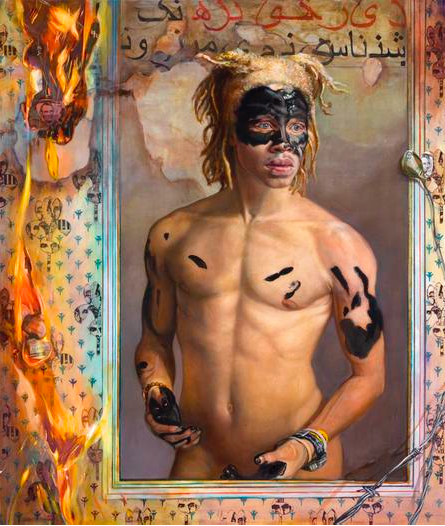

I met Margaret through a photographer who I met on a shoot for Faded Royalty, a men's clothing line. The experience of posing for Margaret was both intimate and graceful. Since I had never posed for a painter before, I was a bit intimidated. That being said, I immediately felt comfortable in Margaret's presence. She made me feel welcome, appreciated, and most importantly beautiful. She made me look very strong and powerful. Her imagery of me was especially poignant and I think she chose me as her subject for a specific reason: being Albino I experience racism more than most people do, from all races.

Margaret Bowland

In learning about his particular past, I learned that Justin is the child of two albino parents, I began by making drawings of him smoking. Then he observed a painting in the studio of a model covered in white paint and wanted to wear make up as well. I let him choose make up colors. First he chose gold and then I saw the Batman bracelet he always wears and I offered him a dish of black makeup. He put his hands into it and applied it where he wished. At first, he wanted to emulate Batman and then he kept going. I just tried to hang on and do the best I could to record what was happening,

I knew what I was painting was a painting about the complexity of race but I wished it to be a fact that the viewer arrived at through time. First you see this beautiful golden boy, then see that he has coated his hands in black paint and applied them to his body. Only after another moment do you begin to see that his features, the texture of his hair, convey to you that he is an albino African American. Through this process I want the viewer to think of what it is he or she really thinks about the relevance of the color of skin.

The issue of race, the color of someone's skin is one of the first visual facts our mind records. And in that second, a door opens and a rush of information fills our unconscious. The conscious mind must then fight past this onslaught to get back to apprehending the person standing before us. We may know these conditioned reactions to be false; we may despise that they exist, but we live within a culture that has created this as the very atmosphere in which we breathe.

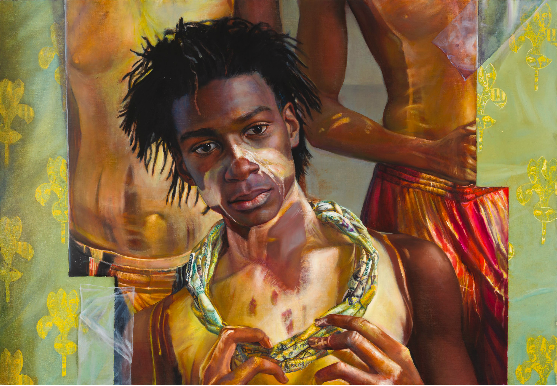

I met Margaret one day by Grand Army Plaza. I was cycling around the park with my friends Nickev and Sherquan and she stopped and asked if I was interested in modeling. She gave me her card and after I researched her I agreed to model. Honestly, at first it felt awkward but after awhile I got to know her better and I felt more relaxed. Margaret made me feel like I could be myself. When I saw the finished painting I was amazed, happy and shocked at how well the painting came out and how. Her theme has so much meaning in the world that we live in today: Power.

Margaret Bowland

One day I was walking in the Park near my house on Memorial Day and as I approached the path that would lead back to my house I looked up and saw Matthew Davis. I did not know his name at the time. He was just a beautiful young man on a bike and the way he looked back at me, his great height and the rise of the ground conjured up in my memory the way it felt to be on horseback looking across at another rider. I looked past his handlebars and there was his childhood friend, Sherquane, equally beautiful and mounted on a bike. The sight of them lifted me back into the great beauty of the world.

I walked up to the boys, asked them to model for me and we made a time to meet in my studio, with their bikes. I had a friend, Frank Turiano, come into my studio at the given time and photograph the boys as I directed and moved them and the bikes about. I did this two more times and was not getting what I needed no matter how hard I tried, no matter how much we interacted. I wanted that feeling of mounted riders and was not getting it. And then I found myself alone with Matt one afternoon while he was waiting for a friend. We were talking and then he turned from me as if looking out the window. When he looked back at me I could see that tears were streaming down his face and he began to tell me of the funeral service he had to attend that week.

Two months back, a kid he had grown up with had caught a stray bullet from a drive by shooting. Matt told me that he had been there and that the police and EMT trucks arrived very quickly. He then said he had stood there, pacing with anxiety while it took the ambulance 30 minutes to drive away. He looked back at me, his face full of tears and asked me why? "Why did it take them so long to leave?" I had no answer but the obvious one, Matt lives in a poor neighborhood.

His friend, whom he had talked to in the hospital the night of the shooting, whom Matt believed would be fine, never left the hospital. He died three weeks later of complications. Matt looked to me, an adult, for the answer. He was terrified of seeing the boy's mother at the funeral because Matt felt responsible. He kept asking himself over and over why he had not done anything? Why had he not spoken to the cops, the ambulance personnel and demanded that they get his friend to the hospital. I knew, of course, that no one would have listened to him that night.

And as I talked to him, trying to remove the guilt on his young shoulders and place it back upon the white establishment I represent, I watched as he shook his beautiful head, watched as his eyes darted in terror and then grabbed on to a smile, saying: "Thanks, I am better, that's just life." Then his friend came and the two left.

Matt and I live two miles from each other at most. A park separates us. The neighborhoods on both sides are mixed racially now, but as Matt was growing up, a black child, his mother had stressed upon him the fear of going onto the streets of the side of the park in which I live, even as I had stressed the same fear upon my children as to the danger possible if they ventured into his neighborhood. Matt is 6' 5inches tall. And yet the first time he came to my studio he had asked me to meet him at the park and together we walked the half block to my house. Even after living in my home for 28 years, this was the first time I really understood that the fear families on both sides of that park had were mutual.

When Matt left my house the day that he had broken down he was not "better." What I had seen in his face was a reckoning with the truth that had resulted in the neglect of his friend dawn on his face and then get driven back down within him. His youth and his beauty supply him with the hope and sheer momentum now that keeps truth at bay. Just like all soldiers, who are always young and anxious to board planes to adventure, we know where those planes lead. I had just seen, twice, the movie "Straight Out of Compton" and as I sat there with Matt scenes from that movie and a Poussin painting in the Met where the golden armor of the soldiers feels oddly made of their own skin, collided and the first of the paintings of Matt was revealed to me.

The next time he and his friend Sherquane came I had them pour gold body paint upon themselves to emulate the Poussin soldiers, and had one wear a necklace made out of five dollar bills to resemble the gold braided necklaces worn in "Straight Out of Compton." Neither of these high school students has one thing to do with the drug trade at all. But I had come to see that they all believed themselves to be soldiers in a world in which they had been raised in an atmosphere of wariness. And the only way out is through gold, through money.

Both boys want to become fashion models and even as I work with them to give them photos for their "books" I know how brutal that world is and how easily it chews up and discards thousands of beautiful kids every single year. So I made my first painting about them and called it Gilt. Yes I am playing on the double meaning of the word but am also asking the viewer to see that even though the main character, Matt, is covered in gold, believing it to be a protective armor his face still shows you what I saw the day he cried in my home, great vulnerability that is not overcome but held in check. His eyes show you what this costs him and the sheer courage he is capable of finding within himself. He is a soldier on a battlefield that is a stacked deck.

For me, his courage amidst this tragedy that is real life, is Beauty. Beauty is being exactly who you are amidst all that the world does to fracture and destroy you. Beauty is courage that some people are born possessing. They do not even know that there is an option called giving up. They hold amidst it all. This is the common denominator in every person I paint. There are no common physical attributes, just this courage. This courage is grace and I know when I am in its presence. My job is to record it.

Margaret is a friend of my family. She asked me to model for her, and I have been for a couple of years. Posing for Margaret is always wonderful because she is easy to relax around and has a big, warm personality. Being a (small) part of the creation of Margaret's artwork is also interesting; I feel as though I have learned a lot about her process just from listening to her and the photographer talking, and from being in her studio. Margaret has a very specific eye for detail; often she'll make changes in my posture or pose that feel miniscule.

During the opening for Power a lot of people asked me the question, "What is it like to be in a painting?" I had a lot of trouble responding to this because it has always been clear to me, especially upon seeing it, that it may be a painting of me, but it isn't a painting about me. I love the painting, but I recognize that the girl in the painting is Margaret's interpretation of my identity, and therefore the girl is more Margaret than she is me. That said, the painting feels very real and honest to me.

I have known a beautiful child, Julia Harrison, for most of her 15 years. She has become preposterously beautiful. She is almost six feet tall, looks like Grace Kelly and is brilliant. This is a young woman for whom no one on earth feels anything but envy. A request for compassion for Julia would bring a smile to someone's face. And yet that very fact reveals the paradox of her need. Julia is like a niece to me. I have watched her develop into this paragon of womanhood warily. I know the world will weigh what she has been given and exact retribution.

I put white makeup on her fair face, just as women have been doing in every culture in the world for centuries. I had her hair arranged on her head in the manner of an 18th century lady complete with the white paint and powder that would have been placed on Marie Antoinette, or Josephine, or Queen Elizabeth the 1st. These women were all turned into blank slates upon which the crowd could project its needs, for purity, or lust or even what it thought to be love. But beneath this mask lived a real woman who was never seen, never known.

I then placed Julia in a turbulent sea up to her neck, her hand trying to pull away the ribbon that such women wore around their necks. The sea in which she struggles fades in deep space into the sea of Turner's The Slave Ship. in her hair are the flowers that would have been arranged upon the head of any great lady of the 18th century but they are made of 100 dollar bills. Those bills carry the image of Benjamin Franklin, the ambassador to France when women were so attired. Overhead are American fighter jets that are igniting the flowers in Julia's hair and fly over the slaves drowning in the water below. This is the world into which Julia was born. For all her good fortune, she still lives in a world that carries this baggage. She was born in this sea. The innocent die every day in wars we conduct and young women are still asked to become projection screens in order to be loved.

Margaret Bowland: Power

Driscoll|Babcock

October 29 - December 19, 2015

525 West 25th Street New York, NY 10001