John Seed Interviews Evan Woodruffe

My mother, father, and two elder brothers escaped the class system of England (dad was born in London's East End), arriving in New Zealand in 1964. They brought very little out with them, but there were some paintings from both sides of the family: a watercolour of Woodbridge by great-great-uncle Charlie, and some peculiar garden scenes by my grandmother Aida Wormald, where she'd used watercolour with almost no added water, so they're composed of very bright resinous drops. My father, John, had been trained in the late 1940s as a designer; one of his teachers was Alan Fletcher, the father figure of British graphic design. In those days, everything had to be hand-rendered, mainly in gouache, and dad still paints very skilfully in this medium. Vivienne, my mother, has a fabulously light touch with paint and pastel, but is too modest to show much. I'm very proud to have one of her keenly perceptive self-portraits. My five siblings are all creative, from my youngest brother Lars, a film editor based in New York City, through Emil (motion-graphics), Kate (PR), Garnham (landscape design), to my eldest brother, Paul, who's been painting much longer than I have. I came to serious art-making later in life, having abandoned my first creative pursuit, music, when I got too old to be a young rocknroll animal.

When I was eight, my parents took us to see Luc Peire's Environment III (1973), which had just been purchased by Auckland Art Gallery. It was a cube one entered, with a mirrored ceiling and floor; I could see myself reflected into infinity, receding forever down and up to an accompanying space-age soundtrack. I felt disembodied, like I was floating off into the artwork. It was an incredible feeling for me at that age. In 2014, I stood in front of the massive Ngayarta Kujarra (2009) canvas painted by twelve Martu women from Punmu in Western Australia. Again, I felt like I was sucked in to the picture, transported to another place, and swore I could see figures moving in the pale central area.

Sometimes a picture can make me cry; the last time was a small work by Henri Fantin-Latour (d.1904), bequeathed to Auckland Art Gallery a couple of years ago. It was just some flowers in a vase, but they were so beautiful, as if they were tearing their fabric to enter our world. There is an excellent book by James Elkins: Pictures and Tears (2001) that looks at this affect, which he calls trance theory: "People who cry in front of paintings are actually taken away: their motionless bodies remain in front of the paintings, but their thoughts are temporarily lost, even to themselves [...] they come back, shaky and unsteady, as if the trip back from the painting led across a narrow bridge suspended high over a gorge". Imagine making such a work? It must only happen to a few, and perhaps only once or twice, and by accident.

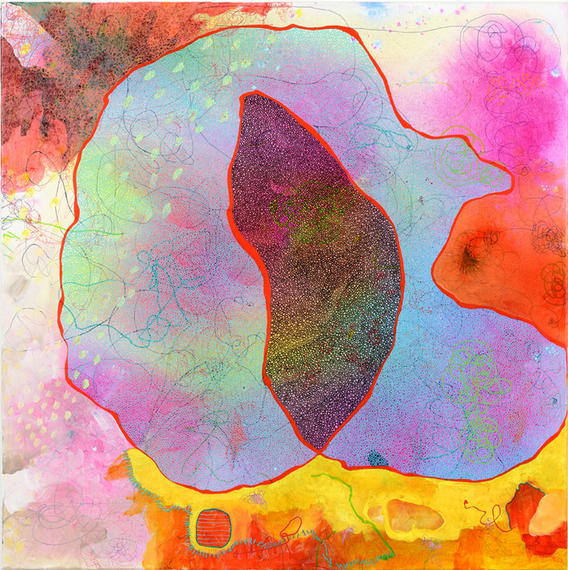

The assertively decorative structure in my work can be linked to Aboriginal painting, though perhaps this is more a regional reference (one that I myself make). For while the traditional Western model tends to avoid the decorative in Fine Art, leaving it to applied arts such as textiles and ceramics, there are many contemporary artists who do employ its all-over effect: Chris Ofili, Ding Yi, Fred Tomaselli, and Philip Taaffe, for example. Taaffe has described using decoration to initially attract viewers, so that their attention can draw out deeper meanings. There are also similarities with the cartographical aspect of the work: there is an archaic approach to map-making, where the Western aerial, topographical visualization is challenged with a more narrative description, a traveling-through approach which can be seen in many non-Western cultures, including Aboriginal. While Aboriginal painting is very specific about place, however, mine attempts to convey a more fluid idea of landscape, one that is less tied to geography.

In both painting and our environment, discovery comes from making a movement through it. The verb to invent comes from in-venire, to come across; so invention comes from maintaining a state of expectation while moving through an area, allowing the discovery of the new. Roberto Matta's approach opens up the way to an image through a series of 'accidents' or informal gestures, as in his painting Bringing Light without Pain (1955), and this is a constant influence in my process: what happens when one doesn't have control? This 'coming across' the image I see also in Dorothea Tanning's paintings from 1957-63, especially in work like Dogs of Cythera (1963), where form begins to shape from a formless flurry of visual information; I love her ability to hold the viewer on the threshold of recognition. While I understand Yayoi Kusama's infinity nets are for her a very real merging of psychic and physical realms, what I'm intrigued with is how they create a filter or screen that fluctuates with its uneven application, generating a rhythm across a surface. This is where my circles come from; for me, they become a permeable membrane that filters, transmits, and connects.

I grew up with art materials, and when my father left advertising to start an art supplies store when I was nine, this immersion increased. I began working there as a young man, but as music occupied my creative drive at the time, I decided to investigate the technical side of the materials. The store was dealing directly with a number of excellent German manufacturers, most notably Schmincke (colour) and da Vinci (brushes), so I was able to talk with people who were not only operating at the height of German excellence, but whose families had been making artists' materials for generations. When I stopped playing music and began painting seriously, I was able to join the technical with the practical and began writing instructional booklets and articles. My understanding of artists' tools was extended by visits to various manufacturers both in Germany and the USA, and after my family sold the business to a large art supplies company, I kept a part-time role for training, demonstrating, and specialist marketing.

In that 'landscape' is a manmade concept and therefore readily available as a metaphor, my work is fed by the idea that our landscape is once again a very baroque one. My understanding of landscape includes the washing hung out to dry in my apartment as much as the trees I see over the balcony. Anselm Kiefer said that one cannot paint the woods the same once the tanks have rolled through them; I add that one cannot paint them the same once the Broadband has been rolled out, either. Our modern landscape includes history, fashion, technology, detritus.

When I walk through my environment I see the sky, buildings, graffiti, people with tattoo, bright dresses, neon signs, trees, litter, motion, emotion - and I check my phone so whatever's happening in world is added to my experience. This is landscape now: a multi-perspective world of clarity and obscuration, fast and slow and totally baroque. Living on some islands at the bottom of the Pacific, I'm interested in how our connection to the rest of the world is deliberated across water. Unlike the tangible nature of land, the ocean is ungovernable, and acts like an unpredictable site of negotiation. The Pacific peoples called the space between islands 'Va', a place of connection, trading, uncertainty, and flux. These values seep into my painting (my paints themselves water-based and fluid), to affect my decisions of colour, quantity and quality. I like the idea of a 'wet gap' that connects everything, rather than us all as dry, separate beings.

I think all painting is unnatural and abstract: with realism, the more one tries for the true trompe de l'oeil, the flatter and less like reality the surface becomes. Conversely, the more deconstructed or abstract an image, the more the eye tries to find a recognizable pattern in it, to return it to form. When I began painting seriously, I decided that I would first need the skills to render things as I saw them. I'm not saying this is how it must be done; it is different for each of us.

Once I knew how to paint something to look like that thing, at least initially, the great difficulty was - and still is - to break that habit. The more one becomes competent, the more one has to fight that ability in order to come across something new. I think that these days to paint figuratively and transcend the abilities of photography and film, one must be really insightful, skilful, and brutal, at least in one's convictions and there are people who are more competent in this than me. A few years ago, I realised that I could excite myself to better results by dissolving the figure into its modern environment; the viewer became the figure in my work, and I attempt to create a shift in their experience of landscape through telling it in a more extra-ordinary manner.

There are so few, the ones that have remained little known should probably stay that way!

How is the art scene in New Zealand?

For a small island country, New Zealand (pop. 4.5 million) has a thriving domestic art scene. There are few who make their sole income from sales, with many also employed in teaching or arts-related jobs, but there is a healthy dealer gallery scene, backed by good public galleries and community art centres. There are a number of significant awards and residencies operating, the Auckland Art Fair attracts galleries from around the region, and New Zealand is represented at several Biennials, including Venice. Operating from an archipelago far from the next landmass has its advantages: the distance filters the international art we see - we tend to see the best and miss the worst, so the bar we set ourselves is high. We are keen to get our work off these islands into the wider world, and so try to locate our work in a wider context. New Zealand galleries are regular participants at Melbourne Art Fair, Sydney Contemporary, Art Los Angeles, and Basel Hong Kong.

I like to eat, drink and dance with my friends and family. My partner and I love the delicate yet strong balance of flavours that make pre-1950 cocktails. Of course, if one is drinking there should also be good food made from fresh ingredients. Dancing helps shake of the effects of both! We both need to travel overseas regularly. This country is a beautiful place to live in, but the isolation makes it essential to get off these islands once a year or so. Seeing how other peoples live opens our minds, and makes us appreciate home too. I like the histories of small things and large. Everyone has some personal history, and all those individual stories combine to make culture. Listening to people tell their stories is fascinating.

Photos by Salt Akkirman

Current Exhibition

Group Show: Evan Woodruffe, Kimberley Annan, George Hajian, Sue Dickson, Virginia Leonard, Richard Darbyshire, Teresa HR Lane, Eloise Cato & Glen Hayward.

Graffiti Lounge (upstairs)

Paul Nache Gallery

89 Grey Street, Gisborne 4010 Aotearoa, New Zealand

February 5-27