John Seed Interviews Jamie Adams

I started drawing when I was about two or three years old. I'm told this was encouraged given my hyperactive condition. My mother called it her pre-Benadryl sedative. My dad and grandfather were avid Sunday painters and I remember spending hours examining my grandfather's landscape painting which was situated in my parents' home.

My father drew pictures from time to time and as a form of entertainment, I guess, he would sit with us and play drawing games. I was the one who seemed to enjoy this the most, so we would sit together where he would begin a drawing and then hand it to me. I would have to figure out what he was looking at and then finish the drawing. So from an early age I learned how to create pictures, compelled to look around, observe things closely, and attempt to describe it visually. It was a great way to play, to explore, and try to make sense of the world around me.

Tell me about your studies at Carnegie Mellon and at The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

I attended Carnegie Mellon as an undergrad in the 80s, when Neo-Expressionism was the reigning international art movement, with its adherents Schnabel, Salle, Baselitz, and others. At the time I was more interested in exploring painting which pre-dated modernism and the 19th century 'brush bravura' aesthetic. There were some excellent faculty teaching at CMU at the time. Herbert Olds was popular, as a consummate draftsman, and he taught foundational drawing and anatomy. A number of my peers who studied with Herb have since gone on to become very prominent figurative painters. Doug Pickering was another notable faculty member. He was a free-spirited, intelligent man, incredibly creative and thoughtful about making things, and exemplified for me what it meant to be an artist in a lot of ways. Other memorable instructors were Mary Weidner, Harry Holland, and Joseph Fiedler to name a few.

Graduate school at the Pennsylvania Academy in Philadelphia came quite a bit later after a decade of raising kids and running an illustration/design studio. I entered graduate school very dissatisfied with my work. It took awhile ripping through a number of fast, and not so interesting paintings before I began to find my own place. The experience was well worth it, working with a diverse and gifted faculty there including Vincent Desiderio, Kathy Bradford, Osvaldo Romberg, Kate Moran, Mark Blavat.

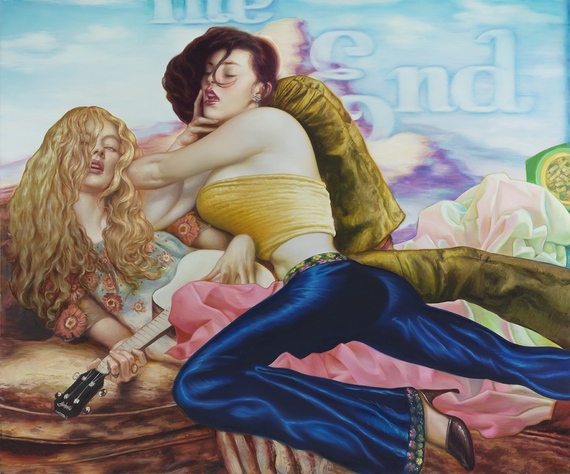

My work continues to function as a kind of personal memoir, drawing from memory, desire, and wishful thinking. Its my response to life, meandering I guess between some form of public confession and private entertainment.

I am nostalgic so I create characters and develop locations from 1950s and 60s cinematic culture, other paintings, and my own dreams.

Prior to the Niagara series which began in 2012 was another set of works I had been working on between the years of 2006 and 2012 called Jeannie paintings. The works were based on a French New Wave film titled Breathless produced in 1959. I made a number of black and white grisaille paintings where the environment was focused on a specific place: a Parisian bedroom apartment in the film. I wanted to insert myself into this cinematic space, take it over, set up a studio.

Eventually I began to speculate about what might be outside the bedroom's window. Oddly, I looked to other films to scout out a suitable location. Older auteur-driven films came to mind such as Bertolucci's Last Tango in Paris, Bergman's Persona, Hitchcock's Vertigo, Sirk's All That Heaven Allows, and Hathaway's Niagara. These included places where my parents had talked about visiting. Where they might have spent their honeymoon... I settled on Niagara.

Hathaway's 1953 film is a tense thriller noir starring Joseph Cotton as a troubled hubby vet and his mischievous wife aptly played by the rising star Marilyn Monroe. Like so many other Post war films--I am thinking of the German émigré Douglas Sirk and his series of lush, colorful melodramas--the film highlights the fault lines in American post-war idealism at the time. Hathaway essentially takes the "Honeymoon Capital of the World" and turns it into a crime scene. Niagara Falls, recognized as one of the grand, natural wonders on the American landscape, and elevated to iconic status through a multitude of luminous American paintings by Church, Bierstadt, Inness, and others, is transformed into what I think to be 'the monster' in the film--the American equivalent to Japan's Godzilla--although much more palatable for an American audience.

I had the opportunity to visit the falls on family vacations a number of times when I was young. There's no way to prepare yourself for the visceral and overwhelming experience standing before such a force of nature. It's one of those liminal spaces, I think, the space in between, constantly moving where everything is in transition, in a state of flux. Your sense of scale is altered by the waterfall's colossal size. I think this is the allure of cinema... besides guiltless voyeuristic pleasure. Having an immersive experience. One that transports us outside of ourselves and into some otherworldly place. This is at least one reason why I make paintings. Wanting to believe in the image elsewhere. This and the desire to replicate the elusive qualities of flesh; the subtle curvature, quick-silver opalescence, translucency...

Tell me about the relationship of your work to film.

I don't think it's possible to make a painting without considering its relation to cinema today (and given the ubiquitous iPhone, any other digital-screen events). Unlike film, painting is not a spectator sport. It invites you to a more active kind of participation and contemplation. As a full bodied experience it functions within its own set of requirements having to do with its scale in relation to space and the body, its physical presence, and surface.

The interrelationship between painting, photography, and cinema is nothing new. Their corresponding interests merely begin with the lens and screen. Painting's pre-filmic urge to animate, extend, or transport the body is a recurring theme throughout its history. I can think of numerous versions of the Three Graces, dating as far back as the wall frieze in the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii, circa 60 AD, prefigure the kinetoscope's sequential images and the multiple viewpoints of Cubism with presenting the female figure simultaneously from front, back, and side.

Other paintings suggest a sequence like Peter Paul Rubin's The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus or later Thomas Eakins' The Swimming Hole, which is painted right around the advent of moving image. The painting likely comes from his time working alongside photographer Eadward Muybridge and his early motion picture sequences. In the East, Huang Gung-wang's hanging scrolls suggested life as a journey or process, anticipating moving image by six centuries.

What are some of the art historical roots of your work?

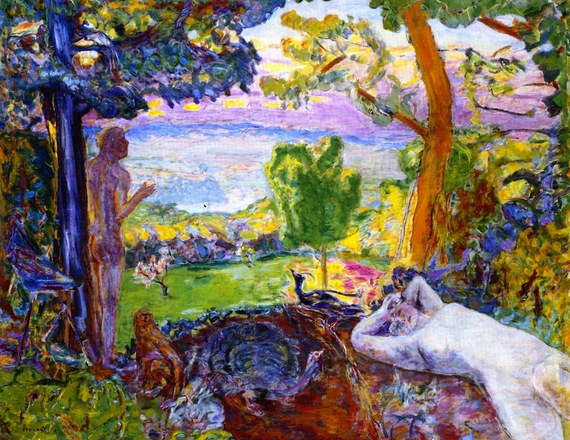

Lately I've been looking at Pierre Bonnard. I see him through his paintings enjoying domestic life after the war with his family and friends in their surroundings. I am drawn to his distinctive, vibrant use of color and unusually complicated spaces. His paintings often seem very quaint, and dreamlike to me--matter of fact. Saying, this is who I am, this is where I live, this is who I love. A few years ago I was walking through the Museum at SAIC with my friend Guy and we came upon Bonnard's lovely painting, Earthly Paradise. I really felt swept up by his emotion.

As a St. Louisan, I love spending time at The St. Louis Art Museum, which has had a long love affair with German art. An entire room of 17 paintings is dedicated to the work of Max Beckmann in particular (thanks to the local collector Morton May), as he gained a following teaching here at Washington University in the late 40s. It is my favorite place to go in the museum. It's not often that you find a museum willing to feature numerous masterworks from an artist's oeuvre--from the early large format 'history' paintings to the more claustrophobic postwar allegorical works.

What are your interests outside of art? The plate is full between prof. practice, teaching, music/soundtracks, films, fashionistas, family (which comes first)--my lovely wife, four daughters (two and a half at home...) and daily exercise with our diminutive 'guard' dog Bruiser.

WINTER INVITATIONAL

Alex Gardner, Ashley Wood, Ben Sack, DALeast, Fulvio di Piazza, Jamie Adams, Jansson Stegner, João Ruas, Kevin Peterson, Lawrence Berzon, MEAR ONE, Sam Wolfe Connolly and Soey Milk. February 20 - March 19, 2016

Opening: February 20th, 6:00 - 8:00pm

JONATHAN LEVINE GALLERY

529 West 20th Street, 9th floor

New York, NY 10011