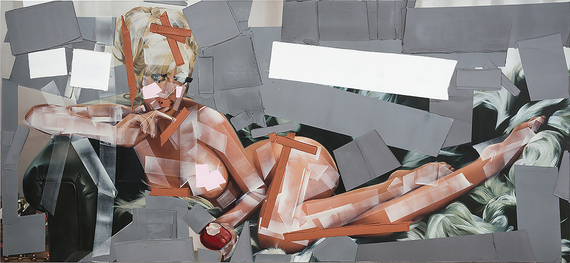

"Painting is something you do with your balls." - Paul Cezanne, quoted by Pablo PicassoYesterday I stood in front of Rebecca Campbell's 13 foot wide canvas Miss April 1971 and found myself thinking "That is one ballsy painting." The painting is on view at the University Art Museum of Cal State Long Beach as part of a dual show: Rebecca Campbell and Samantha Fields: Dreams of Another Time, and it stuck me as somehow being both the best and worst painting on view.

I know, there must be a better adjective than "ballsy" but that is the adjective that intuitively flew into my semi-muddled middle-aged male mind. Given that I am applying it to a painting of a woman--a 1971 Playboy Playmate--which was painted by a woman for an exhibition that has a Feminist context, it's a pretty awkward word, but possibly a compliment. I'll know in a week or two if I can remove the "possibly" and make it an unqualified compliment, but Miss April 1971 has given me a lot to consider, starting with its subject matter: a vintage Playboy centerfold, obscured by wide swaths of paint.

Maybe it dates me--in fact it totally dates me-- but when I was growing up Playboy centerfolds were risqué. In sixth grade a classmate unfurled one in front of me on a yellow schoolbus one day, and I still remember how hard I blushed at the unfolded pink secret. Fast-forward to August of last year, Playboy has published it's last nude centerfold, as internet porn and Instagram nude selfies have rendered simple nudity more than passé. Still, the power of the centerfold lingers, both as a historical trope and as a nostalgic reminder of what fading patriarchal Puritanism once found subversive: flossy, sexually available female nudes.

No painter of women was ever more reckless or aggressive in his depictions of the female body. Picasso re-formed women into personal objects of desire, complicating them and adding a bit of himself to each one: doing so was his macho prerogative. In the space of his work he damaged women--as he did in his life--and the damage was directly connected to his artistic virility. As he once explained it: "Every act of creation is first an act of destruction." It is a dynamic that Rebecca Campbell is clearly very aware of. "Picasso would twist a woman in space so you understand the totality of the eye," Campbell explains in a recent blog post. "I'm curious to explore our paradoxical relationship to these patriarchal images of beauty and desire, at once seduced and repulsed."

Raised Mormon, but now a self-described "pillar of inconsistency" who is using her art to act on her growing feminist insights, Campbell has found a way to re-vivify and complicate the meaning of the centerfold by bringing it home: to art. In the case of Miss April 1971 her approach was to smother the nude centerfold image with ribbons, veils and slabs of paint, selectively obscuring erogenous zones and violating its seductiveness. The artist's eyes--female eyes--were now in charge of what searching glances could uncover. Veils of paint also cover the playmate's eyes, complicating the possibility of any "Lacanian gaze" that she can exchange with her viewers. A scab of rust-colored paint similarly cancels the sensual suggestions of her open mouth.

"Some of my favorite male creators are broken," Campbell notes. "Belmer, Balthus, Scheile, DeSade, Fragonard, Cheever, Bataille. I want this privilege for myself. I want to explore dissonance and instead of having it translated into a betrayal of my gender it might be translated as a meditation on the labyrinth of our human experience."

It takes courage and confidence to tolerate dissonance and viewing Campbell's painting objectively takes both. I'm still challenged by it and in fact this might be a good moment to say that I don't think I actually like the painting. Still, I have to acknowledge that its striking and confident reversal of power has me off-balance... in a good way. Campbell's ability to do what Picasso once did--to use art as a supernatural way of shifting the balance between art and its creator--is undeniably strong.

Rebecca Campbell and Samantha Fields: Dreams of Another Time January 30 - April 10, 2016 University Art Museum, CSULB

1250 Bellflower Boulevard

Long Beach, CA 90840−0004