Basquiat's art is full of letters, words, phrases, epithets, names and logos and they are absolutely essential, fully integrated components of each image, always insistently hand-drawn. He was, all at once, an artist, a poet, a scholar and a scribe: maybe a linguist too. By working with such unity of purpose, Basquiat was touching on an ancient way of thinking. In Egyptian hieroglyphics, for example, words and images had once been conjoined. The literate, highly educated individuals who created hieroglyphic scrolls--whether they were copying or writing original texts--were artists in the broadest sense.

Later in history, as language increasingly became represented by alphabets that stood for phonetic elements, letters retained traces of their kinesthetic roots. The development of words and alphabets started in the mind, but then entered into the world through hands holding styluses, brushes and pens, as did drawings and paintings. In the Western tradition, words and images gradually separated and divorced in the span of time between the Renaissance and Modernism. The illuminated manuscripts of the Medieval period, with their shared reliance on calligraphy and imagery, were replaced by icons and pictures that relied on increasingly sophisticated visual representations: the invention of movable type took over the job of lettering and turned bookmakers into mere craftsmen and printers. Painters made paintings, architects drew, and authors wrote words as specialization separated their tasks.

There were certainly exceptions--for example, William Blake and his illustrated poems--but words were now mainly for books, contracts and signs while images played the singular role of convincing us that what we were looking at just might be real. A fascination with materiality seems to coincide with the rise of Capitalism, the modern West's subsuming religious force. Until photography came along, art images were windows through which we could witness things, and be moved by their validating realness. Words told us things while images showed us things: both did what they could to entice and convince us in their own ways.

It's interesting to note that things developed differently in Asia and the Islamic world, where calligraphy remained revered and essential. In China, where children still learn to write with a brush, the literati ideal of poetry and image being conjoined is still strong: interestingly, so is the idea that a landscape can be a mindscape. Islamic iconoclasm has had the long-term effect of making the tradition of calligraphy its most revered visual art. Calligraphy in Islamic culture is primary, taking priority over imagery and rendering the messages of the Qu'ran as sacred, poetic and imperative.

When American culture was being born and shaped in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, calligraphy meant John Hancock's oversized signature on the Declaration of Independence. The only writing that could be found in and on paintings was generally a discreet signature in the lower right corner. It wasn't until the bits of signage and text included in European Cubist pictures began to nudge Stuart Davis and a few others to bring stylized words into their canvases that the old marriage of words and images could be truly reborn in American art.

After the war, in the era of Pop art, when culture replaced nature as art's dominant subject matter, words no longer had to knock at the door of culture and ask to be let in: they became were suddenly honored guests. Lichtenstein's giant comic strips and Warhol's blandly painted transcriptions of advertisements were the "illuminated manuscripts" of a new kind of mass culture. Many of America's notable contemporary artists have since used letters and words prominently in their art: a very short list includes Jasper Johns, Ed Ruscha Jenny Holzer, Squeak Carnwath and Robert Indiana.

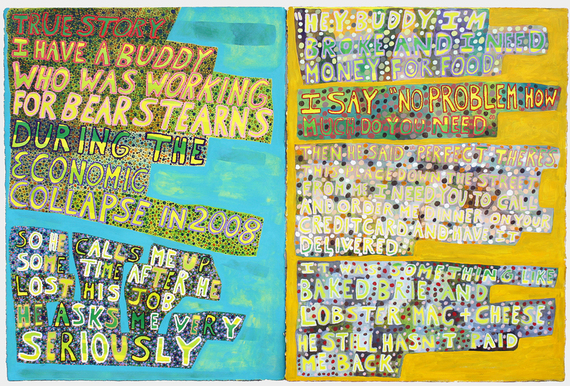

Painted Words presents an eclectic and hasty selection of a rising generation of artists who are--in varying degrees--scholar/scribe/poets. Some artists are here because their representational paintings are activated by the presence of words. Others use collages or palimpsests of words to play the edges between poetry and narrative. Some have been inspired by or even use the street and its landscape of signage. The mechanically printed words of newspapers, album covers and posters make their appearances, lovingly painted by hand.

There are paintings made from words, and words made from paint. Words, in painted form, find themselves layered, blended and brushed towards poetry. One artist--Sandow Birk--has honored a non-Western tradition by asking himself the question: "What would an American Qu'ran look like, and what kinds of images would it include?" There are also works presented here that blur the lines between painting and sculpture.

We live in a media society--and a digital society-- and I'm quite aware that the torn green "M" on a can of Monster energy drink, the digitally printed Star Wars logo on a t-shirt and every internet meme I have seen on Facebook are the mass-produced cousins of the works of art I have assembled here. Words and images are together everywhere in advertising, which media theorist Marshall McLuhan felt was "the greatest art form of the twentieth century."

I would like to think that if McLuhan was still alive he would recognize that visual artists are taking back some of the territory of advertising and re-consecrating the marriage of words and images in the twenty-first century. I have kept my choices purposely broad, with only one over-arching requirement: that I can detect the ambition of art-making as the motivation behind each image. Scholar/scribe/poets are thriving now, although many of them call themselves artists. Each of the artists presented here is doing something strong, original and personal in the way they navigate the overlaps of language and aesthetics. Their approaches may be new, but the tradition they are part of is as old as history, or perhaps even a bit older than that.

View more images...

This essay accompanies the works of 22 artists in a free online issue of Poets and Artists.